Author: Kim Morgan

Nightmare Alley Oscar Nominations

Martin Scorsese on Nightmare Alley

From the LA Times.

Commentary: Martin Scorsese wants you to watch ‘Nightmare Alley.’ Let him tell you why

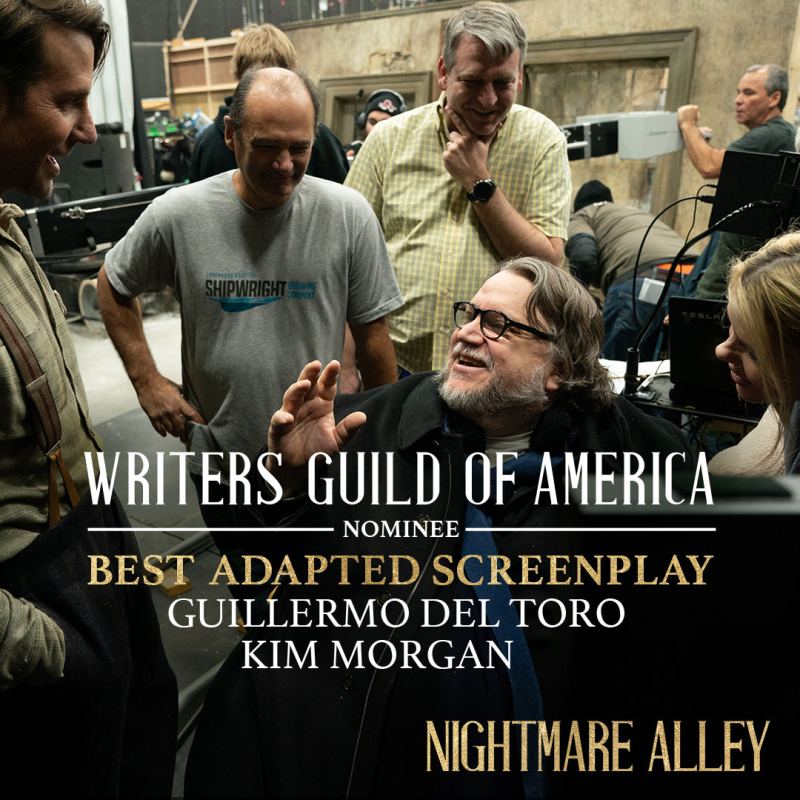

Nightmare Alley WGA Nomination

Nightmare Alley at the New Beverly Cinema

Nightmare Alley Interview Los Angeles Times

(Writer-director and producer Guillermo del Toro and writer Kim Morgan at the premiere of “Nightmare Alley” at Alice Tully Hall in New York Evan Agostini / Invision / AP)

Interview with Mark Olson at the LA Times for Nightmare Alley:

"Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro’s last movie, “The Shape of Water,” was a box-office hit that won four Academy Awards, including director and best picture. The film was a delicate, delightfully weird love story between a cleaning woman and a fish-man kept at a top-secret government facility. His follow-up, “Nightmare Alley,” is a bleak tale of carnies, grifters and a dishonest society that creates a far more despairing portrait of the world.

With a similar visual style to Del Toro’s previous work, beautifully lit and finely crafted, “Nightmare Alley” steers the veteran filmmaker into new territory. The departure includes the fact that Del Toro co-wrote the screenplay with film journalist and historian (and new wife) Kim Morgan."

Read the interview here:

Nightmare Alley — Opening Today!

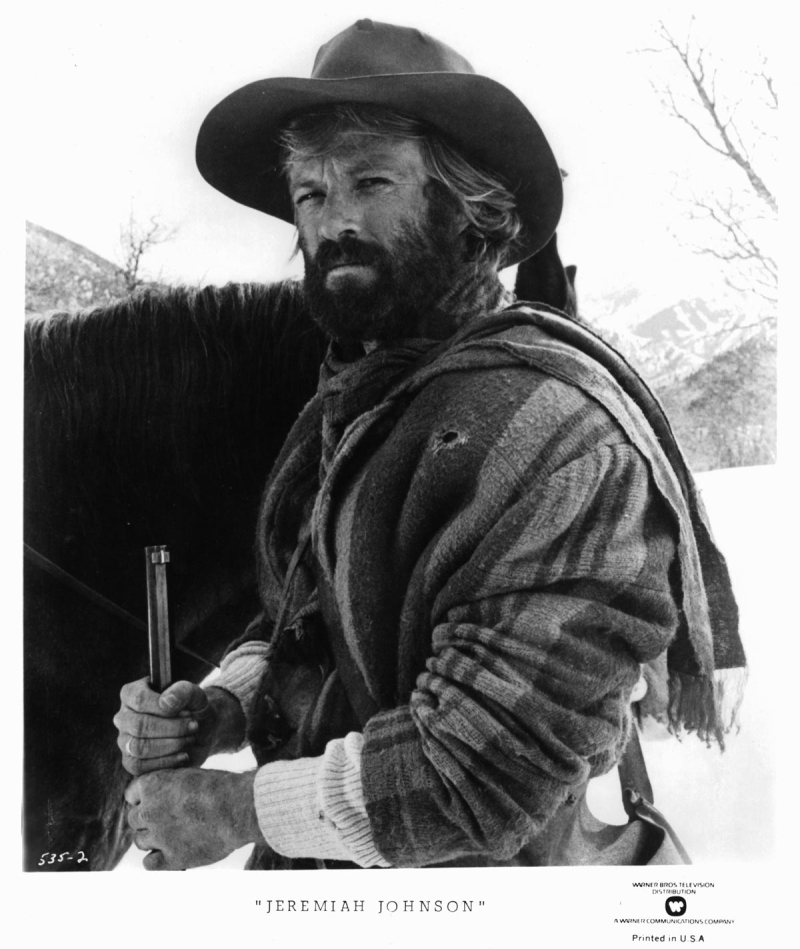

‘Rhythms and Moods’: Jeremiah Johnson

It’s a pity Gloria Beatty never met Jeremiah Johnson. They’d have some things to talk about. Gloria and Jeremiah, two characters in Sydney Pollack’s sixth and seventh pictures respectively, were asking similar questions, albeit with slightly different ends. Where can you? Can you ever escape this life? How do you survive? For Jane Fonda’s Gloria in Pollack’s They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? the question is answered with a poignant, yet bitterly grim no. No, she cannot. The movie is set up like a trapped life – the dance hall and that endless marathon, where she hangs on to live and to ultimately die – it’s like living inside one’s depressive, claustrophobic self. There’s nature out there during the weeks-long endurance test, and it’s close – the Pacific Ocean is just a stroll away. You watch characters reach to see the sun, hear the waves and feel the water pound underneath the dance floor. The ocean outside is endless and you sense it’s there as the dancers move in a somnambulant state, part masochism, part survival. You start living with them – will you ever see the ocean again? Will you ever be free? Will you even care anymore? Gloria Beatty cares so much that, if this seems possible, she can’t care anymore. But she wants to be free. So does Jeremiah Johnson and, as the narrator of the movie states, he “said goodbye to whatever life was down there below.”

Though there is, as often the case, a hand-changing production history behind the picture (at one point Lee Marvin was attached, then Sam Peckinpah with Clint Eastwood), Pollack’s exquisite, contemplative Jeremiah Johnson seems a fitting follow up after the entombed lives and one-room dance hall of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? The vastness and, at times, heartbreaking beauty of the Rocky Mountains (shot in Utah) is what many of the Horses dancers might have imagined as they draped themselves onto one another. Gloria’s death, her final shot in the head, is met with a fantasy image of her collapsing outside on an expansive soft field. Nature. Freedom. But for a man leaving civilization, Jeremiah Johnson proves that freedom isn’t easy. Or as Gloria might say via Kris Kristofferson: freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose. You’re not sure where 1850’s mountain man Jeremiah Johnson (Robert Redford at his most understated and poetic) falls on that idea — what’s at stake — until he loses everything he finally cares about. But then freedom turns to anger, and vengeance is a trap in itself. He feels so angry at times that he seems angry he’s even alive. Like Gloria.

Johnson is a war veteran who sets out to the mountains to find a new life, a sense of discovery, and a purpose, whatever that may be. An 1850’s dropout, he rejects convention to instead live a hard, solitary life in nature as a trapper – not an easy occupation. One might call him an early hippie, and both then and now, his choice seems an attractive one at first, until you understand how tough the life of a trapper actually was (also see the Hugh Glass inspirations, Man in the Wilderness and The Revenant). This is a mythic story inspired by a real man (John “Liver-Eating” Johnson – with John Milius and Edward Anhalt working from Raymond Thorp and Robert Bunker’s book, “Crow Killer: The Saga of Liver-Eating Johnson” and Vardis Fisher’s “Mountain Man”) and the movie potently reflects on nature, companionship, violence and death with the same kind of lyrical meditation and visual pull of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? Pollack, who is rarely considered a stylistic director and more, a highly intelligent, thoughtful, but glossy (gorgeously glossy) Hollywood filmmaker, once again shows his expressionistic, meditative side, unafraid of both the relentless ballroom “Yowza-Yowza-Yowza” of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? and the superbly visual, sparsely storied and silent-film-like nature of Jeremiah Johnson. Like Horses source novel, in which Horace McCoy brilliantly blended a hard-boiled style with a poetic stream of consciousness, Jeremiah Johnson takes Milius’s initial script, which Pollack stated was much more violent, and melded that roughness with doses closer to Henry David Thoreau’s transcendentalism. The “style and size” of Milius’s script was there, according to Pollack, but the narrative was altered and the film made “out of rhythms and moods and a wonderful performance.”

And it is a wonderful performance. Much of this film is watching rugged, enchanting Robert Redford – catching fish in a stream, coming across a dead frozen man in the snow (a bracing, strangely beautiful scene), mentoring with Will Geer’s “Bear Claw,” communicating with Native Americans, falling in love with the Native America wife he didn’t ask for and the son he accidentally inherited – and like Pollack’s dancers of Horses, we move along with him, fixing on his face and actions and even refocusing as the changes happen throughout his journey – his journey to… somewhere. We’re not sure where. When he settles down with his wife (she’s a gift from a tribe) and adopted son, he domesticates himself somewhat, builds a cabin, hunts for food, and, for a time, seems content. He wasn’t expecting a family but he rolls with it and feels a connection. This requires little dialogue on Redford’s part, he’s so persuasive – you can see it in his eyes, his understated gestures, and inner turmoil. When he feels attraction for his new wife (whom he’s gentle with), he simply holds her closer. It’s a small moment that’s more romantic than a kiss. When he asks her why her chin is red, she points out his beard – the look on his face tells you what happened, how close they’ve become. It’s a lovely scene. In these tender moments, I thought of Peter Fonda’s also elegiac western, The Hired Hand, and Fonda’s sensitive, skillfully internal performance in which the wandering man returns home to the wife he left behind, only to take a chance and shatter that life again. In Jeremiah Johnson, home finds him. And then his home is destroyed.

When his wife and child are killed by the Crow Indians (against his own warning, he helps the U.S. Army Cavalry save stranded settlers – they travel through a sacred Crow burial ground – and that creates murderous ire), Pollack gives Redford the time to grieve. The movie lingers on his face overpowered by sadness, but with subtly (there is no moment of grandstanding in this performance) and we take in Redford mourning and thinking, the cabin shading from light to dark to light (the picture is gorgeously shot by cinematographer Duke Callaghan). After that melancholic moment, the lonely man has to move on. He walks out of the cabin and burns it to the ground. That life is over. His new life begins, and it’s a violent one. He starts killing.

Is the vengeance so sweet? No, it is not. It is out of survival and anger, and this somewhat peaceful man who once protested undue violence becomes a blood-soaked killer (the liver eater of the inspiration) and quite good at it. He’s both feared and respected, a living myth. It doesn’t come as a surprise that there’s a rampaging murderer inside this man – that’s not the point, we’re all potential killers – and the scenes play out exciting, but also terrifying and cynical (forget any hint of Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” nonviolence business). But to Pollack’s credit, how we’re to process this is left for us to deliberate. Bloodlust does not seem to be the answer to anything here. What is the answer? Pollack seems well aware that watching Native Americans slaughtered in movies is not as satisfying nor as easy as some westerns would show, but he also doesn’t flinch from the violence and the momentary satisfaction of killing for vengeance. It’s purposely muddy – he’s not a hero.

Pollack originally wanted the ending to be more like They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? – with death. Johnson was to freeze to death. Another way out, another escape — a victim of nature, both spectacular and unforgiving. Instead, the movie settles for something that’s not as tragic – mystery. This is not Gloria, whom, in spite of her death wish, we so want to live. And, so too with Jeremiah Johnson’s murderous death obsession, we want him to survive. But perhaps the picture’s finality is, in fact, scarier because it settles on ambiguity – a big question mark. Johnson and the Crow Chief exchange a respectful, possible moment of peace. How is that going to work out? In this big bad beautiful world? We don’t know. They don’t know. Perhaps we should ask Gloria Beatty.

Originally published at the New Beverly

Frank & Eleanor Perry’s Ladybug Ladybug

Mrs. Forbes (Kathryn Hays) hears the alarm. She sees a letter in a series of squares, and it beeps and lights up. She’s the secretary to the principal of a grade school in a rural area somewhere in America in 1962 – and she’s pregnant. A thin woman well into her pregnancy she moves with ease but, with that child growing inside her, she seems extra vulnerable. Just the vision of that pregnant woman in her dress and the alarm and the light and her concerned face – already we feel creeping dread.

The day did start out somewhat nice – chatting with another teacher and a little boy already sent to the principal’s office so early – she appears to be starting the morning like any other. Mrs. Forbes is kind to the little boy, Joel (Miles Chapin) who was supposedly bad (he seems more like he’s been picked on), and that makes us like her. One woman (a kitchen worker) gives him a treat before he trudges to the principal’s office. She says: “When you’re in trouble, it helps to have a cookie in your pocket.” How moving that gesture seems before what will unfold, and how extra poignant it is when we walk through the entire movie — Frank Perry’s Ladybug Ladybug (written by his then-wife, Eleanor Perry, whom he worked with frequently, and adapted from a short story by Lois Dickert).

And we really do walk through the movie – with those kids, with a teacher. So much that, we, too, begin to feel flustered and exhausted and worried. That cookie could offer such comfort – not just for the sweet taste, but for the soothing memory from the adult, the idea that this adult, this person in charge, thought you deserved it, even if you thought you may have done something bad; and especially if you thought something bad was going to happen to you.

But why should these kids feel so guilty or bad or punishable? It’s the adults who create this kind of chaos in the world. They even later vote on it – they don’t want any kind of war.

These kids – with varied levels of worry – some calm, some distraught – suspect something bad is going to happen to them. And it grows and grows and grows….

So, when the alarm goes off, Mrs. Forbes doesn’t panic; she just isn’t sure if it could be serious. It feels like something. She rushes to Mr. John Calkins (William Daniels), the school principal. He inspects what is going on – and they have to take it seriously. They have to evacuate the school. This could mean … a nuclear attack is about to happen. Given this time period (the film was released in 1963, after the Cuban Missile Crisis), it’s not paranoia to worry. But, no one totally believes it, right? At least they don’t want to – at first. They round up the kids in groups and select teachers to walk those kids back to their homes (Mrs. Forbes and Mr. Calkins stay at the school).

This begins Ladybug Ladybug. A beautiful, haunting, at times terrifying picture, it’s powerful and all-so-human to this day. This was the second film Frank Perry made with Eleanor Perry after David and Lisa. They then took on The Swimmer (starring Burt Lancaster), a transfixing, potently allegorical and disturbing adaptation of John Cheever’s short story. The Swimmer was a stressful production. The direction was taken away from Frank (an uncredited Sydney Pollack shot the rest) but what you see is another expression of the couple’s lyricism and cynicism that, through the early 60s and up until 1970, made them two of the most unique and fascinating independent filmmakers of that time. Among their work, they also made Truman Capote’s Trilogy, and the moving and disturbing Last Summer (I wrote about the film here)– a complex film about troubled, confused young people, and one that takes place on a leisurely beach, but a weirdly empty beach. Grown-up kids from Ladybird Ladybird?

Their partnership ended with their divorce (Frank went on to make films without Eleanor, notably Doc, Man on a Swing, Rancho Deluxe, the great, incredibly underrated Play It as It Lays (which I wrote about here) starring Tuesday Weld in an incredible performance. He also directed the infamous, and I think, impressive and powerful, Mommie Dearest. Their last film together was one of their very best, Diary of a Mad Housewife, an especially lacerating portrait of matrimony, a dreamlike, almost mentally insane spell of both abuse and masochism.

Probing the sweetness and alienation and/or rot within adolescence and adulthood, or the challenges of childhood – particularly within the supposed stability of regular America or suburbia, or of marriage – you truly feel unsettled watching Ladybug Ladybug. The filmmakers take time with these scenes, they take care with these child actors (all of the actors from kids to adults are spectacular), never talking down to their characters, but never fearing to show how negative, even scary some can be (one in particular).

Ladybug Ladybug, with its stark, black and white cinematography, laced with lovely artful touches (there’s a scene on a hill that recalls Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal), feels dreamlike. A nightmare, in fact, but one that works as a direct story of fear (it was based on a real incident), and how the children and adults handle themselves. How quickly the veneer of childhood innocence, of safety, can be shattered. The look of uncertainty and sadness on Mrs. Forbes’ face as she walks through an empty schoolroom, picking up the tiny chairs, organizing the miniature pots and pans on the play stove, placing a tiny man and woman together, staring out the window adorned with paper children, is so beautifully realized, so mysterious, so sincere.

The woman slowly falling apart is Mrs. Andrews (Nancy Marchand), whom we follow as she leads one group of children to their respective homes in her uncomfortable heels. She walks with the kids behind, feet hurting, her face registering increasing amounts of dread and fear and sadness (when she is all alone, she is picked up by a truck driver who plays music loudly – and she laughs a bit but then settles into a look of absolute dread – she is incredible in this little moment). The kids talk – they wonder if the threat is real, some seem almost casual about it, others horrified. One little girl vomits on the side of the road – the poor thing bolts to her father’s work, and he acts like she’s a hysterical nuisance, then, when home, her mother says she has nothing to worry about. The girl grabs her pet goldfish, hides under her bed, as a dark shadow falls over her face. It’s heart breaking. Another kid goes home to grandma, who is suffering dementia or something like it – and they hide in the basement. He convinces her to come down by telling her it’s all play – “It’s called Hide-From-War-Game,” he says. Two other kids make it home and pray with their religious mom in the cellar – it feels more disturbing than soothing. Another little girl, Sarah (Marilyn Rogers) rushes home but mom’s not there. What to do? She’s got to find the rest of the kids. Where are they?

The rest of the kids are in bossy Harriet’s (Alice Playten) family bomb shelter, already dealing with Harriet’s demands and orders. We don’t entirely hate Harriet – after all she’s just a little girl – but we don’t trust her at all, we don’t like her, and she shows how inflexible and heartless some can become in moments of crisis.

Of these kids – we really focus on two of the older kids –Steve (Christopher Howard) and Sarah. Two sensitive kids, they are starting to develop a deeper connection, a first love, with one another. As they increasingly believe the world might be ending, their plan to meet next week for a date (she invites him over to listen to music) is something they are holding on to – seriously – and the actors register this in their faces so beautifully. When Sarah runs to the bomb shelter for safe harbor, Harriet won’t let her in, in spite of Steve’s protestations. Sarah is crying and banging on that door, but, nope, Harriet won’t allow entrance. It’s a chilling moment only softened when Steve runs out of the shelter, possibly risking his life to find Sarah.

And here’s the most haunting moment of the film. Nowhere to go, searching around the barren landscape, Sarah finds an abandoned refrigerator in a dumping ground. She climbs inside of it and closes the door. Steve runs right past it. He doesn’t know she’s in there. And we don’t know if Sarah is going to suffocate in that fridge. It’s a scene I will never forget. It’s a scene I watched with a friend who thought he’d never seen this movie before and that moment bubbled up in him, like a repressed memory.

Characters are trapped in the Perrys’ films, literally, in refrigerators, or swimming pools, or in marriages and affairs giving no profound satisfaction or release. Burt Lancaster banging on the door of his empty house, as if he’s trying to break through to another consciousness or world (one he’ll never reach) while revealing how lonely and empty he feels, is a refrain in the Perrys’ work. Here, he and Eleanor are working more overtly within a trapped landscape – one of uncertainty. Most of the kids don’t know what is really going on and Steve, running to find Sarah, to find somewhere, sees a plane overhead, and, with fist clenched, yells, over and over, “Stop!”

You get the sense it’s not going to stop – the false alarm, yes, this will be known – but the fear of war? That’s going to linger and take those kids into the late 60s when some could be drafted into the Vietnam War, when some will grow up and follow orders or not follow orders, or not trust anything. There’s an interesting conversation that happens while the kids walk:

Brian: I wonder how it feels to see a dead person?

Harriet: You’ll see plenty if the bomb comes.

Sarah: I don’t want to hear about it.

Harriet: You have to face facts.

Steve: It’s not a fact! The bomb doesn’t have to come.

Sarah: So, there. So, shut up!

Harriet: Watch out who you’re telling to shut up!

Watch out.

(From my 2019 piece in Criminal)

Richard Fleisher’s Violent Saturday

Regular small-town American life. Regular small-town American life in the 1950’s. What did that ever mean? The “regular” part? By regular does one mean purse snatching librarians, bank clerk window peepers, cheating wives, drunken husbands and little kids ashamed of their fathers for not serving in the war? Yes, that sounds about regular (it does).

And then Lee Marvin. (That’s not so regular because… who is like Lee Marvin?) But … Lee Marvin. Lee Marvin’s inhaler knocked out of his hand when a kid bumps into him on the street – and then the sharp-suited, blue hat-clad Lee Marvin cruelly presses his shoe on the kid’s hand when the little boy politely attempts to pick up the inhaler for him. “Beat it,” Lee Marvin says to the pained child.

To be fair regarding regular small-town American life and Lee Marvin, Marvin (as Dill), doesn’t live in the Arizona town of Richard Fleisher’s Violent Saturday (1955) – Dill is there for a nice little (violent) bank robbery he’s part of (with his partners, Harper (played by Stephen McNally), and Chapman (played by J. Carrol Naish). But even Dill reveals he’s attempted some kind of domestic normalcy (regular, again, whatever that is) – once. It didn’t take. In one of the best scenes in the movie, Dill wakes up the night before the robbery thinking too much about his life. Perhaps the town (of which we’ve been introduced to in just some of its domestic dysfunction – we’ll see more of it later) is getting to him. He walks (with an intriguing, strange sweetness) into Harper’s room clad in pajamas and talks about his past marriage while, perpetually stuffed up, he’s sniffing his inhaler (presumably, Benzedrine) – a fascinating detail here – that Dill is also likely a drug addict. He says, “I must have the heebie-jeebies or something, I can’t sleep.” After lamenting that their partner Chapman is “mean,” which is a little hilarious given how Dill treats children (later on cool-headed Chapman will give a clearly violence-fascinated kid a candy while he’s robbing the bank), Dill extends Chapman’s meanness to women:

“There’s nothing in this world as mean as a mean woman. You know I got to thinking about all the things that have happened to me on account of women in there when I couldn’t sleep. Boy they can sure ruin you… Remember the broad I married, Harp? Back in Detroit? There was a real dilly for you. When I first married her, I thought she was a real sweepstakes prize. Well, a little on the skinny side, but that’s always how it’s been with me. No meat on ‘em. Just skin and bones. I wonder why I go for skinny broads? Parmalee. That was her name… Left me for an undertaker. No kiddin’, a lousy, two-bit undertaker. To tell you the truth I was half glad to see her go. She had too many bad habits. Got on my nerves. She used to go around the apartment all day in one of them, uh, you know, Chinese housecoats. Practically lived in it. Screwy habits like that. And all winter long she’d have a cold. Boy, she was the world champion when it come to a cold. And every two weeks, I’d catch if from her. (sniffs inhaler) I’ll bet I caught better than 50 colds from that broad. (sniffs inhaler) That’s what started me on this.”

Yes, even Lee Marvin’s Dill got dumped for some regular run-of-the-mill undertaker. After this amusing monologue (beautifully delivered by Marvin), Chapman and Dill hear a noise outside. They check it out. Just a man walking his dog. Regular American life.

Not really. Or, yes, really. That dog-walker is the peeper – mild-mannered bank clerk Harry (Tommy Noonan). He’s married, but that doesn’t stop a Peeping Tom, and he’s about to scope pretty nurse Linda (Virginia Leith), hoping to catch her as she undresses with the blinds open. But he bumps into another townsperson who is also up to something no good – Elsie (Sylvia Sidney), the thieving librarian, stuffing a stolen purse in a trash can. Well, Elsie knows what Harry’s up to, and Harry knows what Elsie is up to, and they share a tense conversation. “I just dare you to go to the police,” she says (understandably disgusted by this guy – though she’s mostly concerned about herself). It’s a fascinating, sad scene – extra layered by the dysfunction that came before it. Prior to this, Linda, who is soft on Boyd Fairchild (a terrific Richard Egan), threatened a man’s wife. Well-off Boyd is married to Emily (Margaret Hayes), who is cheating on him with some lady-killer named Gil (Brad Dexter). Boyd gets soused at a bar, and Linda sees Boyd home – she gets him nicely tucked in on his couch. Nothing happens (though the two like each other a lot) and Boyd’s wife comes in – late. “All I want is an excuse to pull the hair right out of your stupid head,” Linda says to Emily.

But the movie, wisely, is not there to hate Emily or to take easy sides. In a moving scene, husband and wife discuss their problems and their hearts – they really do love each other. Emily, upset with herself says: “I’ve read about people like me. They’re sick people. They shouldn’t associate with decent people.” (Who is “decent,” the film seems to be asking and what does decent mean anyway – a good question) Boyd calms her and they plan to make it work. Things will be better by morning.

Well, no, they won’t. Tomorrow is Saturday.

With the town’s own emotional drama building up to such a fever pitch – it seems like the movie is just waiting for an explosion of some kind, and this gives the crime story of the movie a kind of extra punch in the gut to human feeling – feelings that are already bruised, bashed around, violent inside – a mirror. It’s a fascinating hybrid (screenplay by Sydney Boehm from a novel by William L. Heath) as directed by Fleischer (who crafted some great gritty crime pictures – Armored Car Robbery and The Narrow Margin among them) who handles the sunlit melodrama and violence with a palpable tension, and an incredible fluidity (the camera movement is beautiful) – emotions and actions in wonderful unison.

There’s so much simultaneous repression and out in the open sadness here – even within the most “normal” family – Victor Mature’s Shelley Martin whose kid, Stevie (Billy Chapin – from The Night of the Hunter) is fighting with another kid over his dad not serving in the war. Stevie thinks his dad is a coward. The kid is going to have to think again after Saturday, as Shelley, of course, is the guy nabbed by the bank robbers and dragged out to an Amish farm where peaceful Amish patriarch Stadt (Ernest Borgnine) lives with his family. Shelley and the Amish family are tied up and left in the barn (the vision of everyone tied up is surreal and hyper-real at the same time – particularly in vivid color and Cinemascope – a disturbing moment), while the men rob the bank, and shoot both Harry and Emily in the process. The peeper lives. Emily, who is readying for her marriage-saving vacation with Boyd – dies. Near the end, broken-hearted Boyd says to Linda, “She looked awful, didn’t she? Like she’d never been alive.” My god. What a thing to say.

Saturday gets even more violent. One of Stadt’s kids is shot as Shelley tries to save himself and the family. (The robbery that leads to the showdown at the barn is superb – tense, honestly adult and scary – Fleisher doesn’t even spare violence against children here, as we also saw with the hand-stepping). Shelley, as played by Mature, is supposedly the marquee hero of the story – and his bravery will, by the end, cause his kid to finally respect him (which is a little fucked up). But it is Borgnine’s sweet Stadt who performs the lethal, live-saving blow (I will not reveal, it is too great a moment), going against his values, his religion – making the ending more complex than one might expect. With this – violence had to be done, we suppose, but it doesn’t make that man feel better (even if his kid has been shot – the kid presumably will live – but Stadt still witnessed the horror and he fears for his child). But it makes Stevie feel better. “Boy, you got all of them, didn’t you dad?” Stevie exclaims to his dad recovering in the hospital. Shelley reminds Stevie, “Being scared is only normal and human. No one was every 100 percent a hero.” Stevie doesn’t really listen. He’s just happy his dad is now no longer a coward in his eyes. Meanwhile, poor Stadt and his family will live with how they feel. And an injured child.

As this film shows, being a lot of things is, as Shelley said, normal and human. The picture is both wonderfully melodramatic in the very best way and powerfully down and dirty violent – bizarre, darkly funny at times, and then bitingly real as only our sometimes bizarre, darkly funny lives can be. The robbery feels real, but it also works in a metaphorical manner. A nightmare. But a nightmare some people don’t wake up from. And one that lingers on Boyd’s mind with almost nihilistic reflection. The grief-stricken Boyd spits, “It’s so stupid and pointless to be alive in the morning and dead in the afternoon.” Pray for a peaceful Sunday. Or never pray again.

From my piece in Ed Brubaker's Criminal