Author: Kim Morgan

Kill Or Be Killed: Pretty Poison

Out now! My essay in the newest Ed Brubaker "Kill Or Be Killed" # 7 all about Noel Black's Pretty Poison starring Tuesday Weld and Anthony Perkins. Art by the great Sean Phillips. Order here.

Here's the first paragraph:

Those little eyes So helpless and appealing One day will flash and send you Crashing through the ceiling — Maurice Chevalier (Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe)

I got a pretty little mouth underneath all the foaming La la la la La la la lie Sooner or later, we all gotta die — Nick Cave

There’s a scene in Noel Black’s 1968 Pretty Poison that’s so creepy- sexy, so erotically unnerving, that it still makes a viewer feel off balance and disturbed in 2017. Tuesday Weld’s beautiful, blonde 17- year-old high school majorette has just bashed some poor night watchmen on the side of the head – near dead. She and her new boyfriend, psycho but sensitive Anthony Perkins, have been mucking around at the chemical plant he works for on one of their dates/clandestine missions. Perkins is loosening a chute that dumps chemical waste into the town’s water supply and, filling her head with lies that he’s a spy for the CIA, she’s excitedly helping him. She loves the intrigue and mischief and she loves being bad. The factory guard catches him and Perkins stares back terrified – for good reason – he’s recently been released from a loony bin. Weld is not scared of anything. She’s a remarkably pretty girl with enviable hair and straight A grades and a bright future ahead of her. She calmly brains the old guy, blood oozing all over his face, and she seems a little proud of herself too. Like she just solved a relatively hard algebra equation. Without asking or alerting the freaked-out Perkins she, with all of her sociopathic common sense and know-how, drags the dying man’s body into the water. He’s now good and dead. And then she sits on his back.

Read it all here.

Scenes From A Marriage: Straw Dogs

“David set it up . . . There are eighteen different places in that film, if you look at it, where he could have stopped the whole thing. He didn’t. He let it go on . . . As so often in life, we let things happen to us because we want it to . . . I’ve had to lecture twice now, really, about the film to psychiatrists . . . They say, ‘How did you find out about this?’ Well, I got married a few times.” – Sam Peckinpah

Romantic relationships, revenge, jealousy, masculinity, femininity… these are complicated matters in life, emotionally messy matters, things that, when up against serious impediments, aren’t easily resolved by valorous, well-adjusted people doing the right thing. And often, when feeling a looming problem, and a looming problem particularly in our relationships, we act out in little ways to both avoid the crescendo of drama while subtly stoking those fires, making what we wish to prevent (total collapse) a self-fulfilling prophecy. Through committing small, nasty acts of reprisal (justified or not justified), grievances and resentment can build and build and build until they are fully ignited, gasoline poured on the flames, the house nearly burned down. This is what happens (and literally) in Sam Peckinpah’s controversial masterpiece Straw Dogs, a movie about a man struggling with his masculinity and what that even means (and unleashing his savagery when pressed in the most extreme way possible) while also observing, in most lacerating detail, a failing marriage – two people falling out of love, and indeed, when all is said and done and killed, hating each other. Scalding liquid thrown on faces, bear trap coup de grâce, bloody bodies piled up in a farmhouse. Through severe, in part, metaphorical terms, Peckinpah’s dysfunctional couple is, by film’s end, stripped of their microaggressions to see things for what they really are – they are not in love anymore and why did they get married in the first place? I can only wonder if Ingmar Bergman saw this picture and admired it. I’m going to believe that he did.

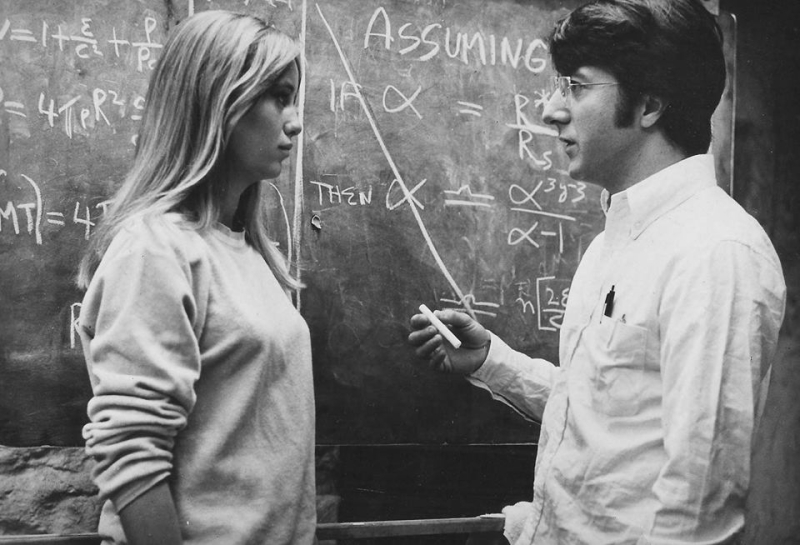

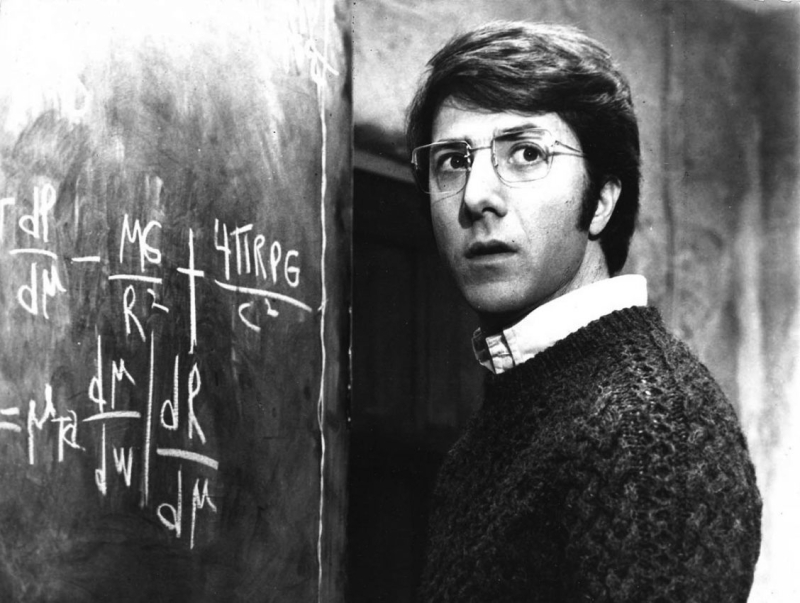

Straw Dogs opens with a Peckinpah motif – children are awful, readying to be awful adults. Like the kids torturing scorpions in The Wild Bunch, the children of this Cornish village (Cornwall, UK) are laughing and screaming and singing while circling a wagging dog in a graveyard. Though the dog’s not tortured, you sense something ominous will happen to the pup, and one can deduce that Peckinpah meant it as such (I highly doubt he opened his film simply to show how adorable little children are). Underneath all of the “cute” childhood play is a creature who could turn around and bite their little hands off. We then see the film’s protagonists walking through town, stocking up on sundries – that’s Dustin Hoffman’s American mathematician David Sumner and Susan George’s Amy, David’s young and beautiful British wife. George gets an eyeful of an introduction, something that’s offended and titillated viewers and critics since its opening: wearing a white sweater and jeans, she is braless, and Peckinpah takes visual notice of this right away.

The male gaze is exactly what Peckinpah has placed front and center (even if women also look at and admire George), as you feel a palpable sense of dread, the townies staring at her as we stare at her, making us feel immediately aroused, and some of us uncomfortable, perhaps even complicit, and a little sorry for Susan George who is simply braless. To a young woman in 1971, going braless wasn’t that big of a deal, and for some (then and now), even if she knows everyone is looking, she doesn’t really care. And why should she? Yes, it’s always wise to assess the danger of your surroundings (and David brings it up later, though with little concern, this isn’t James Stewart lecturing Lee Remick about wearing a girdle in Anatomy of a Murder), but the idea that she deserves any kind of aggression based on her lack of an undergarment is absurd. I can’t believe that I’ve read this subtly questioned, even in reviews from the 2000’s. I recall reading that Amy was “gallivanting around” in one piece, which suggests she’s being overtly ostentatious in her attire. Jeans and a turtleneck sweater? I’ve seen sexier getups worn by Marcia Brady on “The Brady Bunch.”

So … maybe Amy just doesn’t like wearing a bra and Peckinpah noted how men view this and placed us directly in that view. It may come off as exploitation at first but it serves a purpose throughout the entire picture. Amy is both knowing and wagging a big middle finger to those who look. Both times she’s caught in erotic visual (topless in the window, or her mini-skirted leg and panties from the car) she stares down her gawkers more with a challenging “what?” than a flirtation. That many critics view this as merely flirting seems strange to me, not taking in the complexities and the impressive subtly of George’s performance.

But that kind of liberated manner is scary in this setting and furthers the animosity the locals feel for Hoffman’s American, whom Peckinpah also describes via wardrobe – ineffectual, sweatered-preppy in white tennis shoes, walking into a pub full of hard-drinking manly men who clomp around in work boots and scruffy beards. David even requests American cigarettes. You feel sorry for him too. He’s immediately an outsider. This is Amy’s hometown and so the watchful locals may make her feel both more comfortably accustomed to their roughness and wary at the same time and yet, she must know they resent this return. Already a man she’s had romantic involvement with, Charlie Venner (Del Henney), is getting aggressively fresh. But you get a feeling, immediately, that something is not right in David and Amy’s marriage; that it likely wouldn’t have worked out even in a different setting. It’s just that this was the entirely wrong town to relocate to. This will be the place to inflame their already apparent strain. Much like the way Guy and Rosemary Woodhouse make a fresh start at the Dakota in Rosemary’s Baby, you can already see the tension before the Satanists show up.

So much of the picture is building on this dread and animosity – between the villagers with the husband and wife, and between the husband and wife alone, that every little infraction is loaded. David has left the states during the Vietnam War (some believe Peckinpah viewed this pacifism as cowardly, I do not think it’s that simple), and he’s trying to accomplish work on complex math problems in the farmhouse. At one point he tells a worker, Norman Scutt (Ken Hutchison), why he ventured out there: “I’m just glad I’m here where it’s quiet and you can breathe air that’s clean and drink water that doesn’t have to come out of a bottle.” It’s an innocuous yet amusing line because, one it’s timeless, someone would say that now, and two, nothing appears bucolic in this town at all – not even the air. Muscularly shot by cinematographer John Coquillon, the town is potently grimy, where nature is tangled and cold, the green of the earth damp and dirty, everything is effectively oppressive, a place where people are self-medicating illnesses (physical and mental) at the pub, and disease-ridden rats are proudly caught by a giggling rat catcher psycho named Chris Cawsey (Jim Norton) who sings this dreary little ditty: “Smell a rat, see a rat, kill a rat!”

Amy and David are always being watched while the men working on the farmhouse lewdly discuss Amy’s attractiveness with perceptible violence, even stealing a pair of her undies. They don’t like David, whom they view as weak, and laugh at him as he attempts to start his sports car – an emasculating moment, backing up when he means to move forward, accidentally turning on the windshield wipers. Amy is the better driver, and the more reckless one as well. People may consider Amy as the most reckless at everything but I believe they both are. Or rather, everything around them is a torrent of recklessness, fueling their normal transgressions.

Adapted by Peckinpah and David Zelag Goodman from Gordon M. Williams’s “The Siege of Trencher’s Farm,” some changes in the script made the disparity between the couple more evident. Their ages – younger – and Amy young enough for us to assume she was once David’s student. The dynamic of teacher-student crush is now colliding with real life, with nature. That whatever intellectual control David had over her before, he is losing his power, and especially in this turbulent, rugged environment. Their bickering is that of a focused academic who doesn’t take his wife seriously (she also seems quite a bit more affectionate than him) and a wife who seeks respect and validation, even if she has to be annoying to get it. Amy is unhappy, even tortured at times (you can see it in her eyes), and young actress George displays this in knowingly subtle ways. She does small things to show her annoyance – crossing out a plus sign to a minus on David’s blackboard, even sticking her gum on it; talking to the workers only to mock David by telling him they think he’s “strange;” yelling at him to question the workers over who hung their cat in the closet (this seems pretty justified, though it would be hard to approach a group of intimidating men, accusing them of killing your cat).

They’re bickering like an old married couple while playing up their roles, perhaps to restore their attraction. In one scene, David gazes at Amy flopped out on a chair and remarks that she looks like a 14-year-old. He playfully drops the age to 12 and then 8, as she vamps up the Lolita wife by smacking and chewing her gum like a sexy teenager. This works for them. In that moment. But not-so-Lolita Amy has her small victories. Like when David says she’s smarter than he thought because she actually understands a mathematical concept or that Peckinpah shows her playing and studying a cerebral game like chess before going to bed. Amy wants to win at something and if chess won’t be taken seriously enough, her sexuality might, and so that sex, her braless beauty, hovers over the picture as, not just a torture device or Amy having it coming, more as impending doom through sexual extremity.

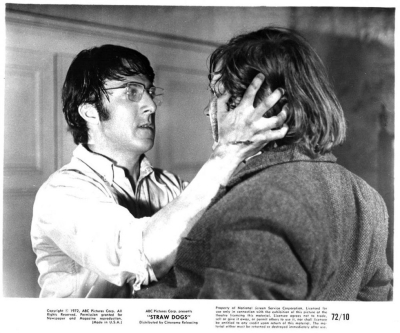

The working men invite David out to hunt and humiliate him further – they ditch him in the woods and one calls on his wife. Charlie Veneer returns to their farmhouse where Amy is alone. Here begins the notorious moment that has been studied, argued about, upset or confused critics to this day: in a meticulously crafted scene, through expertly horrific, ferociously real and yet, hallucinatory directing, editing and performance, Charlie rapes Amy. And then Scutt sodomizes her. It starts with Amy rejecting Charlie’s advances, but he overcomes her on the couch. Peckinpah does not spare Amy, her clothes are ripped off, breasts revealed, her quaking fear so evident you know (and this was indeed true) that the actress is terrified herself. What offends many is that Amy eventually succumbs; she climaxes and holds her ex lover tenderly. When Scutt sneaks in, unbeknownst to Charlie, Charlie at first tells him no, but then, disgustingly siding with a buddy over a woman, holds her down while Scutt rapes her. It’s horrifying, Amy convulsing in terror and pain. Critics who loathe the picture feel that Peckinpah is suggesting that Amy is asking for it, through her attire, through her flirting (I still don’t view her as merely a flirt) or, that craving his masculinity, she’s turned on by Charlie’s brutality. I don’t think it’s quite that simple (though I’m not going to tell anyone what they should or should not be offended by). Amy is being victimized by someone she knows and, in my view, could be submitting to save herself from being further brutalized. She can’t overpower him. She can’t even move. It’s shocking and unhealthy and it makes her feel undeservedly guilty. To underscore this, the scene is intercut with David out in the woods, feeling like an idiot for trusting the brutes, holding a lifeless bird he shot with the look of someone who is thinking, what is the point of this? He’s no idea what is happening to his wife – making the rape also serve the purpose of ultimate cuckolded nightmare – something he’ll later learn and replay in his brain over and over – that she liked it. This is what men might think, even if a woman does not enjoy it. And this it is where many critics draw the line. Amy is traumatized and suffers a traumatic flashing, which returns to her in recurring trauma that will likely never leave this woman. Never mind the man’s issues. Amy has to live with this. It’s a fucked up moment, complicated and troubling but no, nothing Amy deserves. And I don’t think Peckinpah would view it quite that simply either. Though I’m sure some would disagree with me.

And this movie was very personal to him, according to Peckinpah biographer David Weddle (“If They Move . . . Kill ‘Em!: The Life and Times of Sam Peckinpah”). As discussed in the biography, the director’s soon-to-be wife Joie Gould was apparently a version of Amy, and David a version of Peckinpah:

“The costumes used for Amy in the final film bore a striking resemblance to Joie’s own wardrobe, and Dustin Hoffman wore many items that could have been pulled out of Sam’s closet. (Peckinpah was dressing – coincidentally or purposely – more preppily than he had in the States.) Peckinpah was not only using his own past as raw material for the film, but manipulating his present, himself and the people around him, to help feed the psychodrama. A dangerous game, as Joie would learn the hard way … The slightest smile or exchange of pleasantries with another male would throw Sam into a fit of jealousy. By the time they returned to the house in the evenings his eyes were two red pulsing sores and his mood swings were rapid and unpredictable. He flew into a rage at the slightest provocation.”

That some critics believe Peckinpah sided with the savage men of the town, and the savage unleashed in passive David seems too simplistic – that he was picking sides and not, perhaps, addressing problems within himself. Pauline Kael famously called it “the first American film that is a fascist work of art.” (Peckinpah was incensed by this review). The director likely viewed himself as both type of man, which, by film end, David is. The film is hard to wrap one’s mind around, or place tidily in a box (just as A Clockwork Orange, also released that year, was and still is) as it confronts the difficult realities of innate savagery – and not for the better of us. But not for any better or for worse – that Peckinpah is observing it’s there and in David’s eventual circumstances, he’s going to unleash (for protection, but also for satisfaction). Even as the brilliantly choreographed siege (arriving from even more violent/sexual hysteria) which takes over the final third act of the movie, is as exciting as hell, it also underscores how fucking unfair everything in this movie (and life) is.

The emotionally disturbed (or simple, one might say) Henry Niles (David Warner) has gone off, quite innocently, with teenager Janice (Sally Thomsett) which enrages her father – the stupid, volatile Tom (Peter Vaughan) – and he rounds up a group of townies, including Amy’s rapists, to find her. Of course they blame Niles who, in an Of Mice and Men-Lenny moment of fear, accidentally chokes Janice to death. Amy and David have left the church party since Amy cannot stand the sight of her rapists, and David hits a fleeing Niles with his car. Taking him home against Amy’s objections (no one in the town trusts Niles), David refuses to release him to the lynch mob outside the house. David finally takes a stand, and not necessarily for his wife – she has turned against him but is now forced to help him because what else can she do when marauders are breaking into her house, ready to kill them? David is sticking up for himself, for his home and for Niles, though Niles seems more a symbol of his rage and pent up frustration, an innocent who inadvertently isn’t innocent (and maybe a savage too, after all he attacks Amy; David slaps him and says, “No,” to him like a misbehaving child). Niles is an enormous organism of confused impulses and guilt, and perhaps, helps David focus his rage to act and think. And David thinks fast when combating such radical violence and horror.

A few critics at the time saw this as implausible and even melodramatic, but to me it’s a vicious fever dream of not just David’s inner barbarian, but of marital discord exploding to bloody bits – every passive aggressive slight, every sexually unfulfilling night, every jealous moment, every moment of feeling lesser, either intellectually or physically, coming to a literal boiling point of hot oil tossed in a rapist’s face. Much like Warren Oates’s Benny channeling his pain and rage and revenge into a flurry of focused madness, driving with that bloodied head in a sack in Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, David must preserve his self-respect, through retribution. But does he? Oates’s Benny has more loving reasons – he’s lost his love to death, and, dammit, “nobody loses all the time,” as he says, but, perhaps through everything, David loses anyway, because there’s nothing romantic about his vengeance. The brilliant Alfredo Garcia, though dark and unsparing, is also romantic, as is The Ballad of Cable Hogue and The Getaway. But David’s just lost his love to … life. To marriage. All pretense is removed as David (and Amy, I think people forget Amy does help David, even if she resists, ready to bolt out the door towards the townies) defend what’s left of themselves against this leering, loathsome, all-impulse, no-thought mob – hypocrites, since they see no connection with their rape of Amy to anything Niles has done.

Amy is just doing what she’s told, we’ve no idea if she’s going to stick around (doubtful she will) as this Frankenstein creature is saved, the child they wrought. The idea that this is a merely anti-liberal, pro-violence movie in which savagery triumphs over passivity seems too easy for such a difficult story with such confused characters in such extraordinary circumstances. As David drives away with Niles, Niles says, “I don’t know my way home.” David, smiling, curiously, remarks, “That’s okay. I don’t either.” Did he find himself through becoming lost? Or is he merely gone? It’s unclear and it should remain unclear. Straw Dogs is overwhelming and, in the end, thought-provoking because even through violence, nothing is solved. Nothing is easy. And, like the best Peckinpah, it forces you (and force is the right word) to look within yourself, to ask questions. As Peckinpah said:

“I’m defining my own problems; obviously, I’m up on the screen. In a film, you lay yourself out, whoever you are. The one nice thing is that my own problems seem to involve other people as well. . . . Straw Dogs is about a guy who finds out a few nasty secrets about himself, about his marriage, about where he is, about the world around him . . . It’s about the violence within all of us. The violence which is reflecting on the political condition of the world today. It serves as a cathartic effect.”

“Someone may feel a strange sick exultation at the violence, but he should then ask himself: ‘What is going on in my heart?’”

From my piece written for the New Beverly.

Rest In Peace Robert Osborne

Sad day. Rest in Peace, Robert Osborne. A big part to my enjoyment and learning while watching classic cinema. A King in the household. So it was a thrill and an honor sitting across from him as a guest programmer for TCM. That day Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was shooting a segment and we were getting hair and makeup at the same time (I was already nervous and in walks legend, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) — Kareem Abdul-Jabbar was incredibly nice and talked to me about the greatness of Peter Lorre. It was wonderful and seemed like an "only at TCM" kind of moment which Osbourne brought out — everyone who loved movies wanted to talk to him. When I shot my segment Osborne put me at ease immediately. He was so gracious and funny and charming and, of course, he knew all about the pictures (Jack Garfein's "Something Wild" and John Berry's "He Ran All the Way"), that should go without saying. He knew about everything and his knowledge and enthusiasm was infectious and so truly respected, which is why audiences were in such able hands and loved him so much. Thanks for one of my greatest movie moments, Robert Osborne (I treasure the framed photo TCM sent after my appearance, signed by Osbourne). And thanks for everything you gave to classic cinema.

Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise

“What was serious was when critics followed suit. But then they became afraid of appearing old-fashioned by defending the cinéma de papa, as we call it. And they made fun of its French quality, which is there. They didn’t do anything – nothing important, anyway. They never made a Carnival in Flanders, a Grand Illusion, or a Children of Paradise, forgive my saying so. They made ‘intimate’ films with some kind of elevator music – like Truffaut. I’m not criticizing Truffaut, but one day we inaugurated a movie theater in the suburbs where there were two theaters: a Truffaut Theater and a Carné Theater. And we went up on the stage together. Truffaut had dragged my name through the mud, mind you, but I was very honored to have my name together with Truffaut’s. I’m not sure he felt the same way. He said so many nasty things about me . . . Anyway, he had no comment, which was easy to do after ten years. He finished his speech by saying, ‘I’ve made twenty-three movies, and I’d give them all up to have done Children of Paradise.’ What could I say after that? Nothing. He said it in front of three or four hundred people, but it was never written down . . . I am not upset with him anymore. At that time, if I was in a studio . . . and Mr. Godard came in, he said nothing to me, not even hello. It’s almost as if he turned his back on me . . . When they said, ‘At least we can shoot on location, something the old filmmakers couldn’t do’ – they shot on location, fine, but they owe that to the talents of the photochemists and engineers, not to their own”. – Marcel Carné

That deep drum. That wonderfully bottomless sound that opens Marcel Carné’s Children of Paradise – an invocation or a demand. The movie announces itself at once with that dum-dum-dum, almost like a rapping on a door, a door you’re perhaps too intimidated to open but deeply curious to see beyond. You want that door to open, if only in your mind (even as you stare at a screen). It’s the sound of being awoken from a dream, bolting up in bed wide-awake – what is that? Who is there? Were you roused from a pleasant reverie or are you still dreaming? Carné places your eyes, mind and ears in a nocturnal attentiveness with that beating, immediately setting you in bracing dream logic that, paired with a closed curtain, ingeniously positions you as audience member, your eyes gazing at the luminous draperies, still shut, your ears perked up by the processional music turned to lush score which promises something grand, something romantic, surely something beautiful. Open, curtain, we think. What on earth lies behind it? This is a movie, not a play, and these curtains don’t appear playful or Brechtian, they seem a portal to another world. Staring at the screen swathed in curtain, just a curtain, a lovely curtain – it’s a singular sensation – and one you don’t forget. If a movie could possibly make you feel both the disparate sensations of being purely in focus and partially off kilter, and right away, it is the masterpiece Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du Paradis). And then the curtain opens.

Right before it parts upward we read on screen, “Part 1: Boulevard of Crime,” and the opulent instrumentation turns to the music of the Paris street, the organ grinder, the noises of show people. Once it rises we observe a crowded Parisian district circa 1827 in the neighborhood of the “Boulevard du Temple” (called “Boulevard of Crime” not for actual theft and violence, but for the entertainments shown there, melodramas and crime stories). There’s a fellow traversing a tight rope, a strong man lifting barbells, a monkey walking on stilts, horse drawn carriages, dancing girls kicking up their legs, vendors selling wares, and a clown-faced barker beckoning men to a tent featuring a beautiful woman. She will be naked, for what other reason would we spy a gorgeous woman in a tent lest she sport a beard. No beard here, but a bath (“Totally unadorned, naked for all to see!”). After the camera pans through this elaborate, exquisitely crafted set with thousands of extras, and moves towards this tent where another, smaller curtain parts (“Our show is enticing. Audacious! Arousing! For those with eyes that see”) we’re finally presented to the woman who will center the story and who will motivate, inspire, instigate, love, break, reject, bewilder all four men around her – Arletty – as the lovely Garance. She soaks in a tub of water, nude, staring at herself in a mirror as the men stare at her shimmering nakedness, not too much revealed, while we, the viewers, look. Triple vision, not counting the camera, a fourth spectator. We see a vision looking at a vision, and one lit so beautifully we’re uncertain if Arletty is not a young woman, but then, she’s not an old woman either – she’s a woman, and a disarming insouciant woman at that.

Carné (and DOP’s Marc Fossard and Roger Hubert) exit the tent to the crammed street and get to the task of introducing the men of the story, as fluidly and as lyrically as the camera moves – these men are connected to Arletty in varied expressions of desire. Bon vivant womanizer Frédérick Lemaître (Pierre Brasseur) is looking for acting work and after eying Garance, he’s so struck by her beauty that he hustles over to her for a flirtation, all wooing and kissy lips. She smiles back and handles his declarations like the seasoned beauty she is, so used to strangers coming on to her that she can give him her mysterious Mona Lisa smiles and say things like, “I love everyone,” with absolute charm. Another one of her most attractive traits, and one that even supersedes her beauty at times, is that she is just so casually cool about everything around her. And not cold, not even cynical, but bemused, charmed, taking life in with the kind of sophistication that makes her wonderfully unclassifiable, devoid of those stock terms writers and critics and people use towards women – the femme fatale, the hooker with the heart of gold – Garance (and Garance through that glorious creature Arletty specifically) does not fit neatly into any of these appellations, she’s instead, an intriguing person, her own artistic creation, and nobody’s fool.

Garance then moves on to her other admirer (who proudly does not love her, and she does not love him, her “I love everyone” then, seems more, “I love no one,” and that makes life so much easier), Pierre-François Lacenaire (Marcel Herrand). He’s a scrivener and a criminal, who writes letters for others, a dandy with his perfect moustache and curly-cued hair resting at his temples, but a dangerous and hard man with his good looking young accomplice Avril (Fabien Loris) who seems to love him, always at his side. (There’s a lot of sexual fluidity in this picture). After meeting this strangely attractive, debauched rogue, Garance and Lacenaire go back into the bustling streets and stop at mime act in front of the Funambules Theater. Once again, another man is entranced by Garance, this time the white-faced, long-wigged mime, Baptiste Deburau (a brilliant Jean-Louis Barrault) who saves Garance from a pickpocketing charge after she’s unfairly accused of lifting a man’s gold watch (of course Lacenaire actually stole it, and of course he walked away). In a brilliantly shot and acted scene, Baptiste, as Garance’s witness, acts out the crime as it happened to the police, impersonating the large man and the innocent lady to both the crowd and Garance’s delight. The art of mime is elevated here to dance, or a surrealistic depiction of life itself, it is so graceful and lovely and entrancing – a simultaneous emulating and bending of reality. Garance thanks him and throws the young man a flower. He is smitten. But as we’ll see through this first act, he’s so innocent that his feelings are almost too much to bear – that feeling of love, overwhelming love, the kind that makes one almost suffer a mental collapse – makes you worry for poor Baptiste.

The other two men – the womanizer and the cruel dandy – they know their way around women, but Baptiste encompasses all that one feels when one senses their heart losing control. It’s romantic but painful, immediately, that dum-dum-dum of the drum, and that Carné and his screenwriter, frequent collaborator, poet and surrealist, Jacques Prévert, knew how to write and script this sensation so quickly without cheap sentiment or spuriousness, is testament to how powerful their alliance was. Upon introduction, vision to word to wordless description connects us to these characters. There is not one wobbly moment here, not one scene that feels superfluous or dishonest. And the movie is three hours and ten minutes long. And I’m just discussing the opening.

The picture is indeed vastly epic, packed with scenery and extras and meticulous set decoration (by the genius Alexandre Trauner), and yet it’s so intimate and free… it never feels trapped on set, even with the theater backdrop (in fact, the theater feels like a releasing outlet for life, both mirroring it and expanding upon its truths and mysteries). The emotions here are both so fervent and even, at times, unconcernedly honest, and the characters so lived-in and of-the-world, we never doubt for a second they could exist as living breathing entities in this grand creation. There are choices characters make for self-preservation over love, but they aren’t presented as tragic with a capital T, not straight away, and yet there are tragic consequences because of these choices, consequences that sneak up on you and leaves you devastated.

Garance will eventually set up life (not marriage) with the Count Édouard de Montrayrich (Louis Salou), whom she likes least of any of these men, but who rescues her from yet more illegal shenanigans (attempted robbery and murder) via bad boy Lacenaire and his backup, Avril. She had nothing to do with it, but the world being the way it is, Garance is under scrutiny as a woman, and as the type of woman she is. The cynical Count represents another form of affection or attention lavished on a woman – she is bought, she is arm candy, she is the mistress – a free spirit and intelligent, this is not her favorite arrangement. Garance’s men are representative of options, but also the varied stages of love as well, or acting, how we may act with loved ones. Perhaps one could have a relationship (or marriage) with all of these types, presented in one person at various times: The reckless, though likable lady’s man, the cruel, sexy, scoundrel, the sensitive, wide-eyed lover/artist and the tedious sugar daddy.

The film presents archetypes without being obvious or hackneyed about it, with Garance both sexual object and mother figure. Where will her fate lie? Does this have anything to do with fate? Listening to rat, thief Jericho (Pierre Renoir, brother of Jean), who observes the actions around him and comments, disparagingly and threatening, we wonder if he, as unlikable as he is, represents a kind of fate. Norman Holland put this beautifully in his essential essay on the film, that Jericho, “the moralist himself is corrupt, a spy, an informer, a dealer in stolen goods, as the Vichy bourgeois often were – or as children can feel fathers are. Jéricho is a city of walls, the obstacles that our characters face in the world.”

The curtain closes on Act One with all of Garance’s choices, with the theater as life in all of its ambition and talent and crime and sex and sadness, blurring from artifice to actuality, and Act Two presents us with “The Man in White” (we hear that drum again, this time we’re wide awake). It’s seven years later and Garance doesn’t love the man keeping her, she loves the one she should love, the one who loves her, Baptiste. Will that work out? Since he’s married to the one who loves him, Nathalie (María Casarès) and has now birthed a child (the moment where the child introduces himself as a spy for his mother to Garance is captivatingly sweet)… no. It’s not going to work out. Garance shows up to watch him perform, in secret, veiled, and his immense talent and gentle soul is likely soothing the coarseness of her arrangement. It’s another act of artifice – the veiled lady, hiding behind a mask just as the mime or the actor or the criminal pens secret letters for pretenders. She is sad, but Garance never says she’s simply unhappy, she describes it poignantly, at one point as an artful mechanism, damaged: “I’m not sad, but not cheerful either. A little spring has broken in the music box. The music is the same but the tone is different.”

Meanwhile, Frédérick and Baptiste have become famous in their professions, Baptiste as a mime and Frédérick in the Grand Theater, even as he mocks a play and its authors by turning a melodrama into comedy. Another act that bleeds into life – Frédérick even joins the audience in a seat from the stage, enraging the writers enough to challenge him to a duel. Frédérick knows his audience and he knows himself so much that living and breathing acting inspires him to use his newfound jealousy over Garance and Baptiste to motivate his performance of Othello, a sensible solution to pain. Lacenaire creates his own life as well, fulfilling his earlier statement that his head will wind up in a basket – he murders Garance’s Count. And Baptiste, now an acknowledged artist, resumes his love with Garance, but it’s too late and too complicated. Baptiste chases after her but is famously swallowed up in a crowd, literally engulfed by real life – art, mime, the theater, cannot save him at this moment. It’s a gorgeously shot scene in a movie so beautifully filmed and lit (the silver of the black and white, the swooping observational tracking shots, the loving detail of a staircase or a circus or the streets or a blind man who really isn’t blind, another deception), that the time Carné takes showing Baptiste’s aggrieved face, one that is no longer an innocent, (he’s now hurt others) makes his pain so palpable, both for love and for finally growing up and absorbing the end of love in all of its excruciating and layered heartbreak is potently expressive. And no one is to simply be blamed; no one is simply demonized. Even Lacenaire sits down and awaits his punishment. This is not a movie made by immature, mawkish people. These are makers who have lived life, lived art, and lived through war.

And one cannot discuss how real life and theater, artifice and authenticity intersect in Children of Paradise without mentioning its historic, tumultuous making, during the middle of German-occupied France in WWII. Carné cleverly set the film in two parts due to the Vichy authorities requiring a film be no more than 90 minutes long, production was often halted, actor Robert Le Vigan was sentenced to death by the resistance and replaced by Pierre Renoir, set designer Trauner and composer Joseph Kosma, both Jewish, worked secretly during production, and by the time of the premiere, when Paris was liberated, the picture’s star, Arletty, was in prison. Infamously, Arletty had fallen in love with a German Luftwaffe officer and for that she was jailed (in a chateau) for her morally treasonous affair. In response to her controversy, Arletty famously stated these words: “My heart is French but my ass is international.” Spoken like a true Garance.

Carné discussed much of this in a 1990 interview with Brian Stonehill (read it all here) for the Criterion Collection. His thoughts on Arletty, whom he worked with in Hôtel du Nord, Le Jour Se Lève and Les Visiteurs du Soir before this (“She was wonderful.”) and the scandal are intriguing:

“During that period, there were snipers on the roofs of Montmartre, and they went into homes and searched apartments. Anyway, he left, and two days later, I got a phone call from him saying that Arletty had been arrested in his house. A bunch of partisans knocked at his door. My friend, like an idiot, opened the door, and one of the partisans suddenly said, ‘Oh, look at the whore over there! Do you see Arletty over there?’ So they arrested her, took her away; they came close to shaving her head at the station. They never hit her, but they were very lewd toward her, called her all kinds of nasty names and put her under house arrest outside Paris. There, she had to go see some kind of judge on a daily basis. The judge began to fancy her. Every day she went, and he joked around with her. One morning he said, ‘How do you feel this morning, Ms. Arletty?’ She answered, ‘Not very ‘resistant.’”

The picture was an enormous hit, and one of those classics that had become so famous, that some younger filmmakers and critics of the early 1960’s turned against it (particularly André Bazin, Francois Truffaut and others at Cahiers du cinéma), for various reasons. Other poetic realists were still embraced, as they should be, like Jean Renoir or Jean Vigo but Carné was treated by some critics (then, not so much now) as old fashioned, or not an auteur, relying too much on collaboration and, specifically, with his screenwriter, Prévert. (Bazin called him “disincarnated”). The accusation of Carné being set bound to his detriment and/or fussy or not innovative seems unduly unfair, as if his type of artifice and collaboration are a bad thing – absurd. (I’m sure there were other reasons and Truffaut changed his mind) The art and life that stimulated movies like Children of Paradise (and the photography of André Kertész and Brassaï, all part of this rich artistic movement), feel as magnificently authentic and as emotionally honest as Arletty’s beguiling smile, or those Children of Paradise, the poor unwashed up in the cheap seats, laughing and even screaming for their entertainment as they nearly fall into the orchestra pit, or that beating drum introducing the picture’s two parts, calling us to attention, thumping right into our very soul. Time to wake up to live and to dream.

Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women

“With my own memories to draw upon, you would think would have an easy time of it. But it was very hard for me to relive my girlhood terror and at the same time to transform the reality of my feelings into the role I was acting. In memory, I still looked at my experiences with the eyes and emotions of a girl, but the role demanded that I see them with the eyes of a tortured woman.” – Sophia Loren

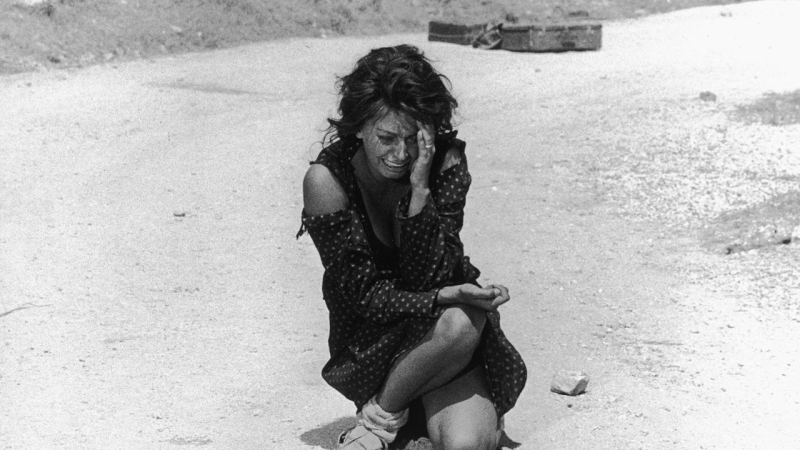

The title of Vittorio De Sica’s Two Women sounds so simple. Two women, mother and daughter, who love each other, enduring difficult, terrifying and heartbreaking circumstances. But the simplicity of that potent word: Women is rendered more powerful by the age of the fascinating females – one, the mother, about 35, the other, a pre-teen on the precipice of what comes with being a woman, nearing that lovely but often confusing and vulnerable age of 13. How she becomes a woman is not necessarily how she becomes a woman, it’s how society might view her as she crosses that threshold, it’s what many tell you makes you a woman, but that her choice towards one aspect of womanhood is taken from her, and taken from her violently (and with her mother enduring the same) gives Two Women an extra dose of sadness and, touchingly, strength.

It would have been a bit different, though certainly horrifying, had the movie followed the novel by Alberto Moravio, more to-the-age, and cast its original pondered-upon leads. Moravio, who also wrote the “Il disprezzo” (turned into Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt) and “Il Conformista” (adapted into Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist), wrote “La Ciociara” featuring a full-grown 18-year-old daughter and a 50-something mother. Most assuredly, these are two women. The book, purchased by producer Carlo Ponti, was originally set for George Cukor to direct with Ponti’s young wife Sophia Loren attached. There was the thought (decision? One never knows what to believe entirely based on various sources of production history) of casting Anna Magnani to star as the mother and Loren as the gorgeous daughter. Wouldn’t that have been something? Cukor left the project and, reportedly, Magnani didn’t want to play Sophia Loren’s mother (though she blamed Ponti for losing the part, citing that Moravio preferred her for the role). De Sica entered the venture with, based on what he’s stated, the clear intention of casting Loren (who won an Oscar for her performance) as the protective mother. Adapting the novel with his frequent and important collaborator Cesare Zavattini (who also wrote De Sica’s most influential, now classic works of neo-realism, Shoeshine, Bicycle Thieves, Miracle in Milan and Umberto D.), the ages were changed – then 25-year-old Loren would play about 35, her daughter (12-year-old Eleonora Brown) would be the young, almost 13-year-old daughter.

Girls grew up faster back then or were required to be adults earlier (though all girls seem to grow up a lot faster than society even realizes), but the age difference was a point to De Sica, for “greater poignancy.” The girl was still a girl. And she’s stated as a girl, a pretty girl, it’s pointed out many times in the picture and by her mother’s adoring eyes, mama showing her off to those not perceived as threatening, laughing and proud. But she’s still a child, and her shielding mother will throw a rock at you if you get too close. De Sica said of the age change: “If in doing this we moved away from original line of Moravia, we had better opportunity to stress, to underline, the monstrous impact of war on people. The historical truth is that the great majority of those raped were young girls.”

That a brutal rape will occur, two, in fact, hangs over the picture with such tension, that even with all the danger of the bombs, soldiers walking the hills, the leering men asking for a bit of leg or the process of surviving with enough bread to eat, the extra terror that comes with being a woman, and two women on their own, follows these characters throughout the movie with a perceptible dread. So much that, at times, Two Women almost feels like a horror film, just as Ingmar Bergman’s The Virgin Spring did enough to inspire one (The Last House on the Left, though Bergman’s masterpiece is decidedly sadder and more horrifying). Two Women is famous enough now (still, surprisingly little discussed and less revered within De Sica’s canon) that viewers know what they’re going to see, but the moment nevertheless feels shocking, not surprising necessarily, though it happens so quickly it does take one aback, almost unexpectedly, but devastating, terrifying. The way De Sica and cinematographer Gábor Pogány shoot this dreadful moment (the movie is beautifully shot in black and white), how swiftly these women are surrounded, the multiple points of view, the setting in a church), never fails to distress me. It leaves a mark.

That the horror occurs when they believe they may be safe, when the war is ending or supposedly over, punctuates how terrible life can be. Indeed, that this mother and daughter have been struggling through the entire movie to be safe, makes this all the more angering over what they must suffer. Loren’s young widow Cesira, a shopkeeper during WWII Rome, leaves the city with her 12-year-old daughter, Rosetta (Brown), to protect her. Enough! The young mother can’t stand the constant fear, the Allied bomb blasts, causing Rosetta to quake and cry. In a stunning, intriguingly shot seduction scene with the married Giovanni, one that at first feels dangerous to Cesira (“Did you hurt yourself?” he asks) and then erotic and interesting (“You didn’t kill me” she says), Cesira sleeps with the lusty man before leaving. Cesira might love him, she’s sad to wave goodbye on the train, she’s happy to receive his letters, but she also needs him to look after the store – the act is both sexual and sensible – and not for one moment does De Sica judge her for this. She heads out for native Ciociaria, up in the mountains, back with the peasants, teaching little Rosetta how to walk with a suitcase on her head the way regular folk do.

They’re vulnerable out there alone, but they laugh and talk and Cesira seems strong – protective. Before, Giovani (Raf Vallone who in real life served with the Communist resistance in World War II) asked Cesira why she married a man she didn’t love; she asserts she didn’t like being poor. “I married Rome,” she says. But returning to her roots doesn’t make Cesira overly proud, she knows where she came from, and she listens to the young intellectual Michele (Jean-Paul Belmondo) talk of how the peasants are superior to city dwellers these days (“They are the evil ones”). Michele, whom we grow to love, and who loves Cesira (she thinks he’s too young, Rosetta adores him) is the overtly political voice of the movie, overjoyed when learning Mussolini has been jailed, angered by anyone’s apathy or willing to take whatever happens at least if the war just ends, but sympathetic and sweet to his family. Still, he says, “If the Germans win I will kill myself.”

It is with Michele that Cesira witnesses one of the film’s saddest, most disturbing moments: they enter a war-torn village seeking food and come across a dazed woman, still young, and in an interminable state of grief. Before realizing how stricken the woman is, Cesira inquires where she can buy food. “Some fruit? Some honey? Little sugar?” The woman looks at the two curiously, and then tells how she was shot at by Germans, making a desperate, dismaying sound of shooting guns. She then opens her dress and pulls out one of her bare breasts. She says: ‘”You can have this milk if you like. I don’t need it anymore. What for? They killed my baby. Who do I give it to? You want it?” Michele but mostly Cesira backs away horrified as the woman starts exclaiming to anyone who will listen among the rubble: “Who wants milk? Who wants my milk?” The merging of broken motherhood with a potential sexual plea, a selling of her body, even if she means her breast for sustenance (the men and soldiers she’ll meet along the way will likely not look at her breasts for food) is surely too heartbreaking for Cesira to even think about, her healthy maternal bond with daughter is everything to her. The ravaging of motherhood, that it means anything to anyone during wartime, works as a portent of things to come. And it’s heartbreaking.

Cesira can’t possibly want to remember that moment. Her sexuality and motherhood is healthy. She knows men desire her, she even likes the attention at times, she knows Michele yearns for her, but she’s more interested in taking care of her daughter. Love will come later. Now, it’s survival and watching her daughter grow up into a beautiful woman with eyes “like stars.” I’ve red some criticism that Loren was too beautiful, too sexy, for this role. That it went against De Sica’s neo-realistic way of inverting glamor – through artifice – like the stark contrast of the lush, but paper Rita Hayworth posters plastered up among the poverty-stricken of Bicycle Thieves. Juxtaposed against such dire conditions, lovely Rita is an unattainable absurdity. But I disagree that Loren would at all mirror paper Rita, or that late De Sica (this was 1960, after his masterpieces Bicycle Thieves and Umberto D. employed not only non movie stars, but non actors) was resting on her glamour.

I think her sexiness, not glamour, but her beauty and eroticism – the way Loren can simply recline on the grass with the knowledge of how enticing she must look, but at other times, have no idea or concern with what men want – shows both how self aware and selfless Cesira is. She was a peasant, yes, but why would a peasant not be beautiful? Or even as beautiful as a movie star? Young girl Loren did not begin as a movie star. We all start somewhere. According to Loren’s biographer Warren G. Harris, De Sica told Loren, “You have actually lived this story yourself, Sophia. You survived the war. You know all there is to know about it. If you can become this woman, without any thought as to how you look, without trying to restrain your emotions, letting everything flow into this character, I guarantee that you will give a wonderful interpretation of it.”

And she does. By the time the rape occurs, we’ve grown to love and admire both mother and daughter, feel warmth and compassion, and we worry for Michele who is taken away by German soldiers. As the war nears its end, mother and daughter feel safe to return to Rome, even amidst the chaos of soldiers and deserters and god knows what else. As vulnerable as they are, they walk along and decide to rest in a church. The bombed-out church is clearly symbolic – this will not be a place of worship, nor of sanctuary nor of peace. Earlier in the film Cesira asks Michele: “Isn’t there some safe place in the world?” He answers: “You can’t escape. And it’s better so.” Perhaps better so because you must know everywhere is dangerous – even a church. Cesira finds some old pews and dusts them off for her and Rosetta to nap on. Rosetta, about to sleep, gazes up at the busted ceiling, her face looking momentarily worried, eyeing such a strange sight. Cesira readies for her nap but spies a man in the room and quickly wakes Rosetta to leave. It’s too late. They are ambushed by a group of men, running and scurrying like cockroaches. The overhead shot is horrifying – we know there’s no way they’ll possibly get away. Gang raped by Moroccan soldiers of the French Army, we see from different perspectives, daughter screaming, mother screaming, and the daughter’s face, close up, eyes wide, in shock, penetrated. De Sica films this so quickly, but with lasting impact, and with such chaos and disjointed intensity that it never leaves you. You can see that Rosetta’s face has literally died inside. After the brutal attack, mother and daughter are alive, but Cesira turns to see Rosetta, a shaft of light from the broken roof shining down on her, dress raised up. She is lifeless, like a doll. They must move along, even after this horrific attack, and walking along the road, Rosetta clutches near her pelvis in pain, wanders to a stream to wash her delicate areas. You just didn’t see scenes like this in movies at that time – the after affects of rape – and De Sica films this unflinchingly but with empathy.

And this is where the other woman comes in. Rosetta is now numb, but out of anger or ingrained cultural expectations, or just shock, she later that evening goes out with a man who buys her stockings. Like a woman. This enrages her mother, worried the act has now thrust her daughter into adulthood too quickly, or that she’ll become a whore (which the movie would never judge), or perhaps that Rosetta will never enjoy love or sex or men in a healthy way. The only thing that finally breaks Rosetta’s traumatized spell is hearing of the death of Michele, and mother and daughter are now nearly in the same position as when the picture started – holding each other, crying, bonding. One could read this as some kind of happy ending, that maternal order is restored even in tragedy, but I tend to agree with French critic André Bazin’s assessment of De Sica; how one can read his pictures. He’s discussing movies like Bicycle Thieves and Umberto D. but I believe Bazin’s thoughts fit in quite well with Two Women:

“It would be a mistake to believe that the love De Sica bears for man, and forces us to bear witness to, is a form of optimism. If no one is really bad, if face to face with each individual human being we are forced to drop our accusation as was Ricci when he caught up with the thief, we are obliged to say ‘that the evil which undeniably does exist in the world is elsewhere that in the heart of man, that it is somewhere in the order of things… De Sica protests the comparison that has been made between Bicycle Thieves and the works of Kafka on the grounds that his hero’s alienation is social and not metaphysical. True enough, but Kafka’s motifs are no less valid if one accepts them as allegories of social alienation, and one does not have to believe in a cruel God to feel the guilt of which Joseph K. is culpable. On the contrary, the drama lies in this: God does not exist, the last office in the castle is empty.”

Or, again, as Cesira asked Michele, “Isn’t there some safe place in the world?”

From my piece written for the New Beverly.

Kill Or Be Killed: Two Savages

Out now! My essay in the newest Ed Brubaker "Kill Or Be Killed" # 6 all about the 1962 "Naked City" episode starring Rip Torn & Tuesday Weld. Art by the great Sean Phillips. Order here.

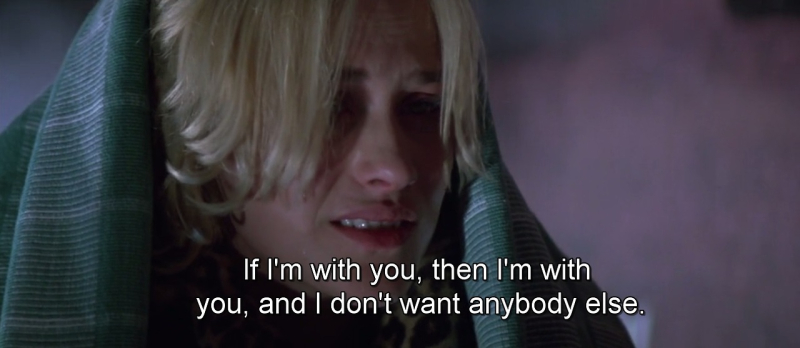

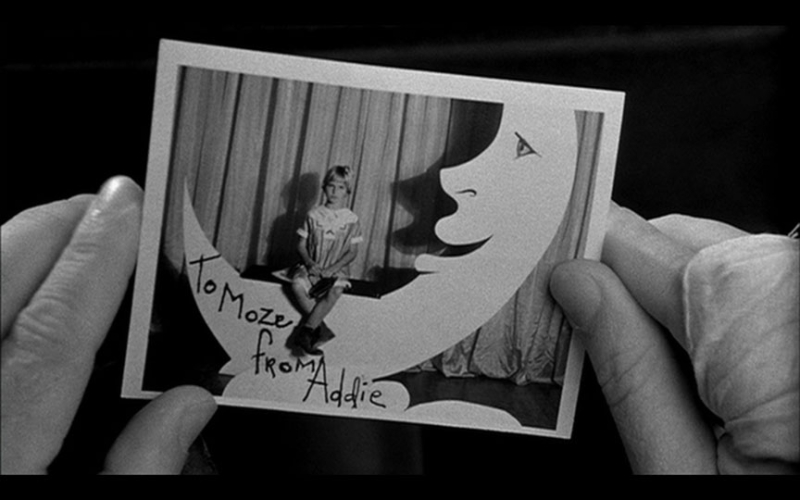

Young and beautiful oddballs Tuesday Weld and Rip Torn — together — in sickness and in health. Underscore sickness. Madly in love, madly in lust, the actors play two recently married, demented hillbillies in heat like ardent caterwauling kitties — cute as hell but dangerous to disrupt lest you’d like your eyeball torn out of your socket. Gorgeous, wild-eyed sociopaths driving down from the hills of Arkansas and into the mean streets of New York City, they yell about traffic, argue over dolls, fix their sites on wedding rings, grab guns and gobble frog legs cooked up by Torn in their dingy motel room. After child bride Tuesday playfully antagonizes Rip, laughing and hitting him with a pillow, they fall to the bed in a haze of pillow feathers, picking feather from hair, lip and eyelash…

Read the whole savage thing … pick it up here.

Happy Valentine’s Day: True Romance

From my interview with the late, great Tony Scott in 2006:

KM: This question is asked so often and hard to answer, but I am curious: Do you have a favorite film?

TS: “True Romance.” I love all my films but “True Romance” was the best screenplay I ever had. And all that was Quentin. It was so well crafted. But I did change the end. Originally in Quentin’s version [Christian Slater dies] and Patricia [Arquette] pulls over on the freeway and she puts a gun in her mouth [she doesn’t die]. I shot the film in continuity, so by the time I got to the end of shooting the movie, I had fallen in love with the two characters. It was a love story. I wanted these characters to live!

There’s a scene early in True Romance in which Patricia Arquette’s call girl Alabama (not “a whore, there’s a difference!” she insists), is so full of love and feeling and guilt, that I’m always (I mean, like every time I watch it) taken aback with emotion. She’s just so moving, so sure to prove her ability to “come clean” that you want to reassure her it’s all going to be OK. And when you first see the movie, you’re a bit worried for her. How will he (Christian Slater’s Clarence) react? Is he going to be angry with her? It’s a moment of truth where a macho ego might lash out at a woman who’s just pretended attraction, romance and compatibility (though she’s not pretending, she realizes, to her delight and fear). It’s also the kind of scene many critics take for granted because, well, it occurs in what would be termed a pulpy action movie. A brilliant pulpy action movie and now a classic and an influential one, notable for the excellence of Quentin Tarantino’s screenplay, but not a movie in which people win Oscars (but of course they should – listing and discussing all of the exceptional, oddball, sometimes brilliant performances in this movie could fill a book).

And though True Romance (directed by Tony Scott) is a lot more than action, and was certainly praised, and Arquette did indeed receive kudos by many, still, within confining categories, her skill of showing such complex feeling in the picture is not recognized enough. Not in the way, again, an Oscar-seeking performance with a big “important” speech would be praised. Well, Alabama hasa big, important speech because she’s a young woman in a seedy, dangerous profession (lord knows how she got there) and now she’s overwhelmed with a passionate purity of feeling – love. And that’s terrifying. She also wants Clarence to know she’s not a habitual liar or “damaged goods” or a bad person after revealing to him that their dream date was actually paid for by his boss. How will he react? Refreshingly and wonderfully (it feels so progressive watching it today), he’s not mad:

Alabama: I gotta tell you something else. When you said last night – was one of the best times you ever had – did you mean physically?

Clarence: Well, yeah. Yeah, but I’m talking about the whole night. I mean, I never had as much fun with a girl as I had with you in my whole life. It’s true. You like Elvis. You like Janis. You like kung fu movies. You like The Partridge Family. Star Trek…

Alabama: Actually, I don’t like The Partridge Family. That was part of the act. Clarence, and I feel really goofy saying this after only knowing you one night and me being a call girl and all, but… I think I love you.

It takes a great actress and a clever, expressive screenplay to balance all of those feelings with such romance, fun and sadness (what has Alabama been through before that?) and Arquette’s angst and relief that Clarence isn’t going to haul off and smack her is so palpable, the viewer buys her insta-love without a doubt. And you buy his love towards her, and not just for her blonde hair and big boobs. The girl’s got heart, as James Gandolfini says as he beats the shit out of her (I’ll get to that other powerful Arquette moment later). “I think I love you.” Hey, that’s the best Partridge Family song (she may not even know that since she doesn’t even like them). But, boom! They are married.

Their swoony beginning seems too good to be true but their chemistry cannot be denied – it’s real. But their future? That’s where the fairy tale is amped up and enters, not just mythic Bonnie and Clyde terrain but the world of the Brothers Grimm or L. Frank Baum – Oz with bullets, cops and mobsters as flying monkeys. Detroit is not Kansas but neither is Hollywood and so their love, writ large, the kind that makes a person crazy and brave and stupid, mirrors the fantastical dominion they’re driving into. And Clarence is nobly stupid at first. Or perhaps he’s nobly stupid throughout the entire movie – he’s clever and cool and even admits he’s an amateur – but he’s as lucky as fuck. Thinking he’s nabbing Alabama’s clothes but is, in fact, actually stealing a suitcase full of cocaine from her Big Bad Wolf pimp (the hilariously, terrifying thinks-he’s-black Gary Oldman), and then kills him, Clarence figures they can sell the goods in L.A. and escape their lives, forever.

And then all… of … this: He says goodbye to his comic book store job, his papa ex-cop (a moving Dennis Hopper, whose Sicilian speech with consigliere Christopher Walken is now famous), drives off with Alabama in his beat-up classic Cadillac, meets up with his L.A. actor pal with a stoned roommate (Michael Rapaport and a scene-stealing Brad Pitt), gets in contact with a Hollywood producer (Saul Rubinek) and his nervous actor/assistant (Bronson Pinchot) and… the insanity begins. Actually, the craziness started back with Oldman, Walken and Hopper, but Clarence and Alabama aren’t entirely aware of all of the layers and levels and twists and turns that are and will happen, culminating in a showdown at the Beverly Ambassador Hotel – cops, bodyguards and mobsters all in a standoff. This is one hell of a story – so vividly written, so smart and hilarious, so violent and nuts, that yes – this is how love can feel too.

It all winds together and explodes in an exhilarating, surrealistic swirl through the unabashedly entertaining, hyped-up and artful direction of the late, great Tony Scott and a poetic, perfecto Tarantino. As I said, I see it as part fairy tale, but also part splashy Hollywood satire about movie people who pile in the coke while making pulpy war pictures, and struggling actors audition for “T.J. Hooker” while their lovable loafer roommates recline on the couch all day, smoking out of honey bear bongs. With that in mind (and if you live in Los Angeles) it’s not even that unrealistic. Like Mulholland Dr. and The Big Lebowski after it, you’ll recognize this Los Angeles on those days when the air feels chemically off – and all of this heightened chaos and absurdity crashes down on you. (I know some of you readers know exactly what I’m talking about) Tom Sizemore screaming/directing Bronson Pinchot’s Elliot, a now wired-up narc with, “You’re an actor. Act, motherfucker!” is a sublime metaphor of how on edge “talent” feels in this town.

Clarence’s negotiations with the coke-buying producer resonates for multiple reasons. Is Clarence ass-kissing to get the deal done like every Hollywood jerk? Yes. But, no, he’s not. He’s genuinely sincere in his admiration of the producer’s movies. Even his guide, the ghost of Elvis Presley (Val Kilmer, post Lizard King) in a bit of sublime fantasia during which the movie again, recollects the dream of Oz – Elvis as Glenda the Good Witch – reassures him he’s not being an asshole. And Clarence, the Sonny Chiba-loving movie fan, talks to the producer almost as if he’s talking about the real-life film he’s currently found himself in:

“You know, most of these movies that win a lot of Oscars, I can’t stand them. They’re all safe, geriatric coffee-table dogshit… All those assholes make are unwatchable movies from unreadable books. Mad Max, that’s a movie. The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, that’s a movie. Rio Bravo, that’s a movie. And Coming Home in a Body Bag, that was a fuckin’ movie.”

And Tony Scott well understood that speech. Scott, who mysteriously, tragically took his own life in 2012, was a popular but supremely underrated director (among critics), one who was often accused of being a lot of flash and crass. He certainly indulged action, sex, explosions and quick cutting (fantastically in many pictures, from The Hunger to The Last Boy Scout to Man on Fire to Unstoppable), but he had wit and intelligence, a dark view of the world met with a smile. His films could be brutal, but they never lacked humanity.

He told me in a 2006 interview: “I have no regrets. I love the fact that people will continue to employ me and pay me to do what I want to do, which is attempt another world. That’s what so great even about this. I get the opportunity to do new things. I get the chance to do the research, educate myself and I get the chance in… touching this word.”

“Attempt another world” and “touching this world” – what a beautiful way to explain his artistry and love. And he as he expressed to me and others, he loved True Romance – he loved Tarantino’s superlative script and he loved all of those brilliant performances. You can feel it in every inch of the movie, right down to the smallest roles. From Oldman to Pitt to Samuel L. Jackson to, of course, James Gandolfini. Which brings me back to Arquette as Alabama and her showdown with Gandolfini’s hitman. It’s a painfully violent, terrifying scene, and Scott and Tarantino spare Alabama no comfort – but they also don’t exploit or condescend to her. Her ferocity in fighting back, her loyalty to Clarence, even the way she breathes and lunges and screams, blood dripping down her face, smiling in his face, middle finger extended high, fills the viewer with a range of emotions, much like her angst-filled confession of love on the rooftop. She’s surviving, and it’s bloody as hell, but it’s supremely moving. When I asked Scott about this scene, he was thrilled by my admiration, stating it was “multi-layered in terms of charm, humor and violence at the extreme. Patricia is unique,” he said. “She’s got this angelic childlike quality yet, she’s got this strangeness.”

Indeed she does. And her sweetness and strangeness match the picture’s pulpy lyricism. When composer Hans Zimmer’s Badlands homage chimes in, at both beginning and end, and Arquette’s loving, haunting narration is heard, an ode to Sissy Spacek, you feel a wistfulness that, though a cinematic hat tip, belongs to Clarence and Alabama as well. They’ve earned that music. And after all the guns and coke and blood and Hollywood craziness, it leaves one with a feeling that bad times are behind you, and hopefully love is in front of you (though one can never be sure). Alabama watches Clarence run on the beach with their child in a final scene that looks like a dream from heaven – as if their character’s never made it out alive, and Clarence really, truly got to meet Elvis. But they do make it out alive. It’s a movie. And, as Scott would say, they’re attempting “another world.”

Tatum & Ryan: Paper Moon

“There was a part in the script and I asked my dad to help me with it, I was still learning to read… and it said that I had to say: ‘I love you’ to him in the movie… And I looked at him and said, ‘I can’t say that! They don’t want me to say that! Why would I say that?’ I wasn’t the kind of kid who went around saying ‘I love you’ to many people, or at least to my dad. I mean, which little girl wants to say ‘I love you’ to their dad? Well, at least this kid didn’t. But anyway, they cut it. And so you’ll see that I never do say that in the movie.” – Tatum O’Neal, 2011

“Tatum has lived more than any 10 people three times her age. I want the best for Tatum, because she has lived through the worst.” – Ryan O’Neal, 1974

Tatum O’ Neal’s nine-year-old face in Paper Moon is the face of thousands of little girls, pissed off at their broken families and their absent dads. It’s a tough little face that’s resilient and smart, because in the movie, life has made her grow up fast (her mother just died, she’s gonna be sour), and it’s a lonely face, yearning for her dad to at least reveal himself. And yearning for him to stick around, not so she can simply hug him and blubber in his arms, but so she can yell at him. Yell at that son of a bitch! Where the hell have you been? Oh, and I want my 200 dollars!

In the movie, we never do truly learn if O’Neal’s daddy, played by her real-life daddy, Ryan O’Neal, is indeed her pops, but they got the same jaw. And they both have a talent for grifting. And she’s so good at trickery that her talent mirrors Tatum’s first-time acting ability – she’s a goddamn natural. Director Peter Bogdanovich (on the advice of his brilliant production designer and ex-wife Polly Platt) was canny and perceptive enough to cast the O’Neals: already wizened tomboy Tatum and her divorced, weekend father (who didn’t see her enough weekends) who were working through their relationship in real life. As Ryan O’Neal said in a 2011 interview alongside Tatum, “I was separated from her mother. So I only knew her on the weekends… But we had good weekends together, really good weekends. I thought that maybe if Tatum and I worked on this picture, it might seal our doom, or our bond. One or the other.”

Doom? That is some tough stuff (read Tatum’s autobiography “A Paper Life” if you want to dig further into this and her entire, tumultuous life). But they are so perfect together, that Tatum, not Ryan, as great as he can be under the right director utilizing his specific talents (see my piece on Stanley Kubrick and Barry Lyndon), is the one who lifts him up to a higher level here. This is one of his greatest performances. I don’t care if she was reportedly a pain in the ass on the set. She was a child. And she breaks through the screen with such charm and charisma and the camera loves her so much that it’s like what Billy Wilder said of working with the brilliant Marilyn Monroe: “She was a pain in the ass. My Aunt Millie is a nice lady. If she were in pictures she would always be on time. She would know her lines. She would be nice. Why does everyone in Hollywood want to work with Marilyn Monroe and no one wants to work with my Aunt Millie? Because no one will go to the movies to watch my Aunt Millie.” Exactly. And viewers and critics liked watching Tatum so much that she won an Oscar for it. Striding on stage in her little man’s tuxedo with bow tie and short hair (GODDDESS), she not only deserved that gold statue but she gave a fantastically brief, no-bullshit speech that adults should learn from: “All I really want to thank is my director, Peter Bogdanovich, and my father. Thank you.”

All of these thoughts flicker across Tatum’s face, even when she’s not speaking her mind (which is a lot), but in beautiful little moments – like when she’s all Leo Gorcey-tough guy, sullenly smoking in bed, or posing pretend ladylike in the mirror, or smiling to herself in the car after getting the better of Moses. There’s many sequences in the movie so expertly shot by Bogdanovich that not only show Addie’s sharp little mind at work (her scheming with Trixie’s put-upon maid, Imogene, played by a terrific P.J. Johnson is hilarious, impressive and genuinely moving for the fate of Imogene too), but the stand-out is an uninterrupted argument between Tatum and Ryan in the car. The amount of dialogue, the comic timing, the way the disagreements flow from “But they’re poorly!” to “Frank D. Roosevelt” to complicated directions on a map, is so expertly handled by Tatum and Ryan, that you’re left a little breathless by it all. These two were made for each other. And that makes these deceptively light moments extra poignant.

Also adding emotional complexity is the gorgeous, effective deep focus black and white cinematography by László Kovács – it isn’t handled in some self consciously old-timey manner. The stark landscape and Dorothea Lange-looking faces have been compared to Bogdanovich’s hero, John Ford, and specifically his work with Gregg Toland on The Grapes of Wrath. And you certainly see and feel that in this picture, but it also achieves a modern European look as well. But then, maybe it’s just a Bogdanovich “look” and I shouldn’t label it as anything else. For as much as Bogdanovich lovingly harkened back to the past with Paper Moon andThe Last Picture Show, he wasn’t merely aping it, or reveling in nostalgia – as touching and as gentle as those pictures are, there is a harder edge to these movies. These were not the “good old days” because Bogdanovich was not only old enough to know better, but he was enough of a film historian to know that old movies never thought the days were so great either. Again, 1940’s The Grapes or Wrath is indicative of this, as well as plenty of pre-code pictures from the 1930s (and how about the 1950s and Elia Kazan and… I could go on an on). Paper Moon is a sweet road movie but it’s also very sad. And timeless – fathers and daughters (and surrogate fathers and daughters) will have strained relationships until the end of time.

And Bogdanovich trusts his actors to know this. With the O’Neals especially, he trusts their own real-life bumping up against the written word. And they know it too. And they and Bogdanovich know that the future is a mystery. Taking the time to look at their faces and wonder what else they’re thinking, or what is down the road or around a corner adds an extra visually potent unknowability about what will happen to these two. When Addie arrives at her Aunt’s house at the end, it’s a nice house, and yet there’s something incredibly depressing about the place. In spite of what any sensible person would say, you want Addie to leave it, and to go back on the road with Moses. And you want her to get that 200 dollars. And you want Moses to be her dad. Who knows if that’s the happy ending?

From my piece on Paper Moon for the New Beverly

Adrian Lyne’s Lolita

From my piece written for the New Beverly

“Then she crept into my waiting arms, radiant, relaxed, caressing me with her tender, mysterious, impure, indifferent, twilight eyes – for all the world, like the cheapest of cheap cuties. For that is what nymphets imitate – while we moan and die.” – Vladimir Nabokov

Adrian Lyne’s Lolita? At the time, the very thought made certain cinéastes and academics shudder. How could the “vulgar” white-gauzy-sex director of Fatal Attraction, Flashdance and Indecent Proposal ever think he could match the brilliance of Stanley Kubrick’s 1962 tragi-comic adaptation? And one starring a Dolores Haze (our great teenage wonder of cinema – Sue Lyon) whom Nabokov himself approved of? Furthermore, could Lyne even touch the poetic resonance, the linguistic ingenuity, the slyly sad and humorous pedophilic venerations of Humbert Humbert from Vladimir Nabokov’s magnificent novel? One of the greatest novels ever written (says this writer, and many others). How could Lyne cover Lolita without getting all 9 ½ Weeks on us? Sadomasochistic role-playing and erotic food-feeding next to an open refrigerator, copious milk guzzling, white cream sliding all over Kim Basinger’s pillowy lips? Basinger is a grown woman. She can guzzle milk and let it run down her face like metaphoric sperm. But a young teenager? Well, a fridge does happen in Lolita: the girl alone at night, spied on by an older man as she enjoys a midnight snack next to the open ice box, eating raspberries from each hand and sucking them off of her fingertips. Lyne likes a good fridge scene.

That young teenager and older man are lovely, scary, heartbreaking, sardonic and powerfully perverse through the written word (a captivating and gorgeously written novel), and were handled with wit, sadness and irony in Kubrick, but with Lyne? At the time, naysayers likely shook their heads or rolled their eyes and, in the case of freaked-out censors attempting to quash its release, wagged their fingers. But both were asking, albeit for different reasons: where does this Adrian Lyne get off?

Getting off is an appropriate/inappropriate question. Given that the film’s controversial source material – a pedophile (technically, an ephebophile) who falls in love with and beds a 14-year-old “nymphet” was such a taboo tale, surely to be made more titillating through imagery, and during a time (1997, when the picture was released), when people were arguing over the photography and, in some cases banning the work of the great Sally Mann or Jock Sturges, eyebrows were raised the moment filming was announced, no matter who the director was (though Lyne had directed the great 1980 teen film Foxes, with a casually Humbert-like character in Randy Quaid). Brooke Shields’ Pretty Baby beauty would not be tolerated or acceptable to admit as sexy then or now (check out Shields’ “The Brooke Book” from 1978 – much collectable now, probably by many creeps), and yet, teenagers and men were ogling 16-year-old Britney Spears a year later dancing in her Catholic school girl uniform to “Baby One More Time.”

But here’s what Lyne did – he made a visually stimulating portrait, a heartbreaking work of lyricism highlighted by two sensitive, provocative performances by Jeremy Irons and Domique Swain (aided by an exquisite, heart-aching score by Ennio Morricone). Yes, the movie lacked the more trenchant humor of both Nabokov and Kubrick (who brilliantly amped it up to metaphorical levels with Peter Sellers’ Claire Quilty as a hilarious, bedeviling double of Humbert), but Lyne’s Lolita was still indeed funny, though subtly so. And Lyne went directly to the tragedy and the romanticism, which felt even creepier, but in the way that it should. He also made Irons’ Humbert watch Lolita, and really watch her, eroticize her, yearn for her. Constantly. In Kubrick’s introduction to Lo, Shelley Winters as mama pronounces that bulls-eye double entendre with “My cherry pies” as Sue Lyon, clad in a bikini, gives James Mason’s Hum-Baby an alluring look-see, Nelson Riddle’s “Lolita Ya Ya” taunting him. She seems to know her power in the moment and what that dirty old man Mason is thinking (read my essay on Kubrick’s Lolita for more on this).

In Lyne’s introduction, Lolita lies in the backyard grass in her own world, looking at pictures of movie stars, a sprinkler spraying near her white, wet dress, which clings to her young body like a perfected David Hamilton image (considering the charges against the now dead Hamilton, this seems even more disturbing a comparison). She looks up at him and smiles, retainer in her teeth. She doesn’t appear to know what he’s thinking; she looks like a pretty adolescent placed in a haltingly erotic composition through the lens of Lyne (and cinematographer Howard Atherton). She will soon know what he’s thinking, but at that moment she’s just relaxing in the grass, and Humbert just stares. He utters the word “beautiful” to her mother’s admiration of her “lilies” (beautiful is obviously meant for another lily), and again, he stares. And stares. You wish he’d stop. But you can’t stop staring at him staring. This is from his point of view and the movie makes no bones or excuses about it. All that discussion of the male gaze, as if females don’t gaze in similar ways (we do), this is a male gaze movie by a man with a problem. And that’s part of the point.