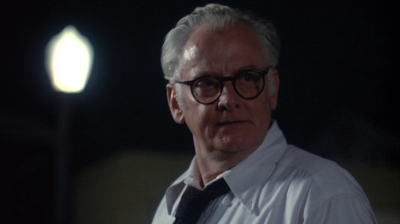

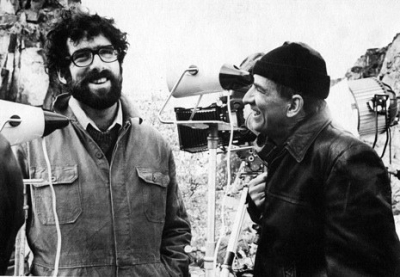

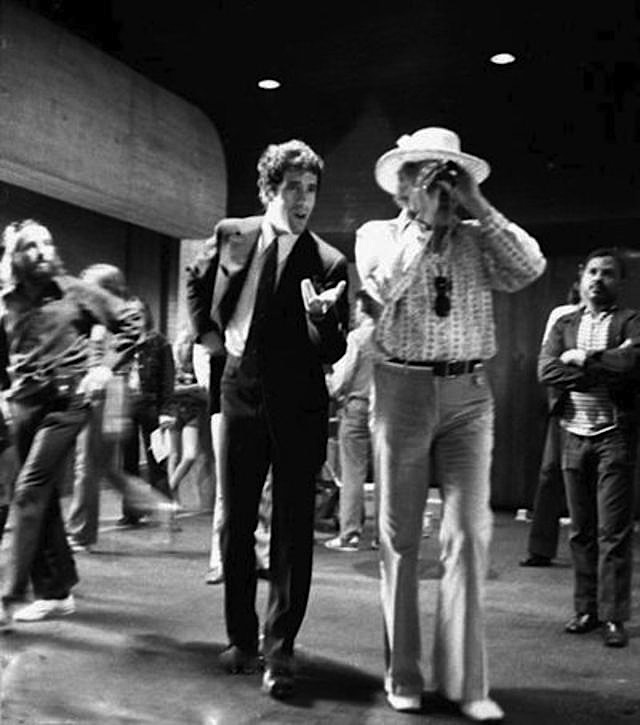

From my New Beverly interview with the great Elliott Gould:

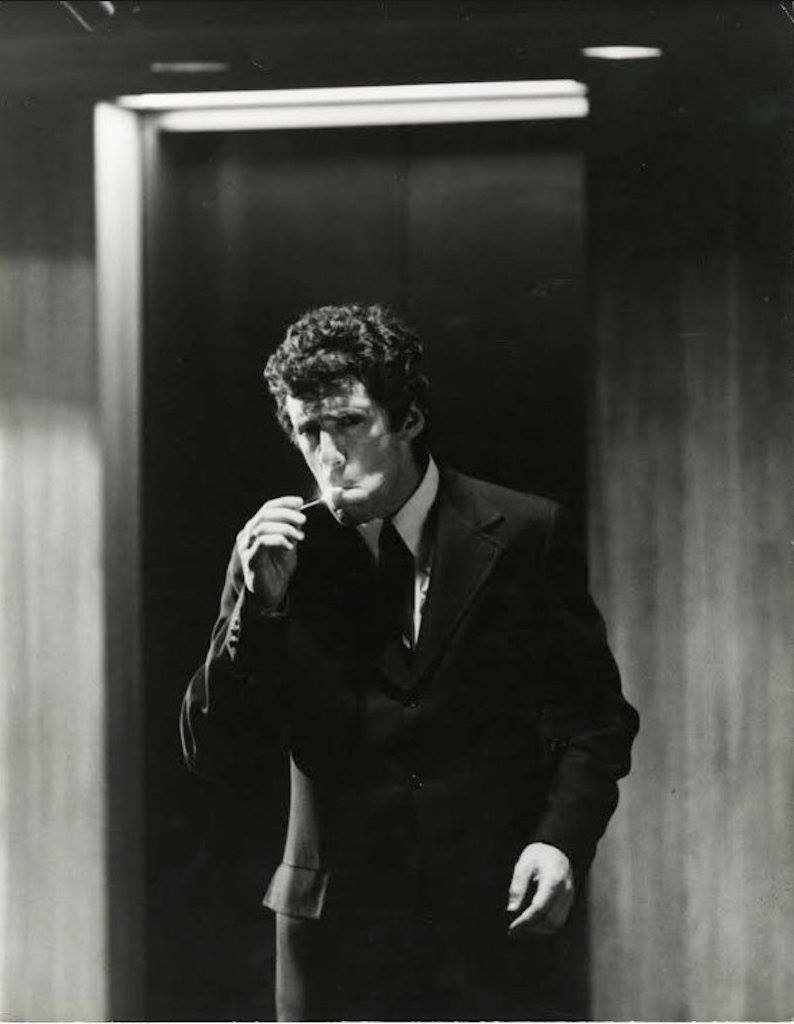

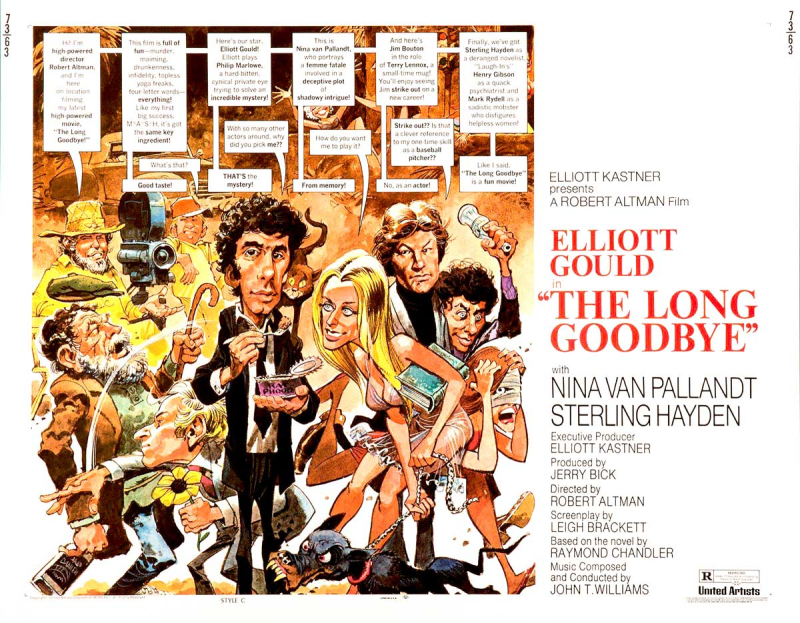

Talking with Elliott Gould is a unique, enriching experience. He philosophizes, he riffs, he free-associates in an erudite, non-linear way that recalls jazz. Jazz – which is how he describes the movie we’re talking about Robert Altman’s masterpiece, The Long Goodbye, in which he unforgettably stars at Philip Marlowe. I met with Gould recently in Los Angeles to discuss Altman’s seminal picture, and the conversation moved to multiple subjects – Altman, Bergman, Chandler, Bogart, identity, freedom, how you can’t double cross a cat … so many things. It’s never not fascinating talking to Gould…

Kim Morgan: I’ll start with the genesis of the project … Can you discuss the journey of this version of The Long Goodbye?

Elliott Gould: I went to visit my friend David Picker who was running United Artists, I went looking for a job or looking to see if I could produce something with someone who seemed to get me. And David Picker gave me Leigh Brackett’s script. And, at the time, I didn’t know if there was a formal attachment with Peter Bogdanovich. I read the script – and I thought it was somewhat old-fashioned … the word pastiche doesn’t come from here, but, still, I was always interested in the genre. I was told that Peter couldn’t see me in it. He saw, in his mind, Robert Mitchum or Lee Marvin. And I said to David Picker, “I can’t argue with them, they’re like my Uncles. But we’ve seen them, and you haven’t seen me.” And then out of the blue I got a call from Robert Altman to whom United Artists had given the material. Altman called me from Ireland where he was finishing Images with Susannah York. And Altman said, “What do you think?” And I said, “I always wanted to play this guy.” And Altman said to me, “You are this guy.” And that was it.

KM: What made Altman decide to get involved …

EG: Well, we didn’t do McCabe & Mrs. Miller (You know I couldn’t do it at that point) and still McCabe & Mrs. Miller didn’t suffer, although I understand that wasn’t so easy for Bob to work with Warren [Beatty]. Bob had said to me, at that time, “You’re making the mistake of your life.” And I said, “Well it’s not my life yet and you can’t take away that I was your first choice for this and someday I will look at this and say, wow what a masterpiece and you wanted me to play it.” Meanwhile Warren and Julie were great. But, Bob and I had done so well with MASH and I guess it was just such a blessing because I was not only out of work, I had gone too far… being that I was producing. But I didn’t understand limitations with the business. I didn’t understand realty with the business. But Bob was certainly perfect for me and we really did great. I thought we might have done perhaps a Raymond Chandler every three years. Just to do the whole thing…

KM: It was already an iconic character but you made it iconic in your own interpretation … but it doesn’t sound like you had any trepidation with this character…

EG: No! Bob gave me so much freedom…. When we [with Steven Soderbergh] were all shooting Ocean’s Eleven, and it was 1:20 in the morning and we were set to do the scene where George Clooney tells everyone what it’s going to be, and I had a little scene with Matt Damon and all of us – the whole group was there – and just as we’re ready to shoot at 1:20 in the morning, Steven Soderbergh walked up to me and said “the ink on the face…”

KM: Yes…

EG: You’ve heard this and you know this. “Was the ink on the face an improvisation?” I’m ready to do my scene with Matt Damon, hit my marks and play my part, and I thought, what are you talking to me about? I have to wake up to respond to your question. And then we said, at the same time, “The Long Goodbye” – I said, “Yes, the ink on the face was an improvisation … was that behavior acceptable to you?” And Stephen said “Yes, but it was so unexpected.” I [told him] that exhibited the kind of confidence and trust that Bob had in me… Here’s this fascist cop who was questioning the character of Marlowe in this little room which was being observed from a two-way mirror, right? I thought in terms of the irreverence of the character and the core, the substance of somebody who will not deviate when it comes to pure nature and justice and what we need to believe in… And the cops saying, “What are you doing?” And I’m saying “I have a big game.” (You know in football they put like charcoal under their eyes to take the glare away) … and just being totally irreverent to the authority that is [pauses]… trying to build a wall on our Southern Border. It’s the same thing…

KM: Yeah …

EG: Yeah, it’s the same thing. Yeah. And then I went even further and put it on my face and started to do Al Jolson … I said, “So once I committed to putting ink on my face… If I had stopped and hadn’t continued and followed through and done it, it would have taken us about twenty-five minutes to clean me up and as you know, movies are about time management in relation to resources. Everything to me is about nature. Everything is about nature. And it exhibited Bob Altman’s confidence in me. I could weep, you know. And his trust in me.

KM: That he let you really improvise.

EG: More than that… because I know when we did MASH, he said to me, a couple of times, and I don’t like the way it sounds but it’s true, “I can’t keep my eyes off of you …I don’t know what you’re going to do.” And I said, “Then don’t look at me. I’m always in character. My presence here once you have a camera and you’re working, I’m always in character so don’t kill what I’m doing until you see it in consort with everyone else. Then, if it doesn’t work, you tell me and I’ll change immediately.” And the next day, Bob came up to me and said, “You’re right.” Bob always had a problem with authority. So, did I… With The Long Goodbye, I felt it was, the first picture for me. The first picture for me…

KM: Really?

EG: Well, I remember each up to The Long Goodbye…

KM: Yes, we talked about all of the movies leading up to this and how important they were to you …

[Gould discussed all of the pictures leading up to The Long Goodbye, what he learned, and the experiences associated with them, from his first picture, William Dieterle’s The Confession, also called Quick, Let’s Get Married, to William Friedkin’s The Night They Raided Minsky’s to Paul Mazursky’s Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice, a movie in which Gould said it was where he discovered his relationship “with the camera and that the camera is my first friend. It doesn’t lie to me, it doesn’t tell me do, or don’t, it just reports. It’s objective. Everything was subjective to me. That was a breakthrough for me. That was a great opportunity for me.” To, of course, MASHwith Altman, and how he was first offered Tom Skerritt’s part but said to Altman, “I could do it. I have a very musical ear, I could do it. But this guy Trapper John, if you haven’t cast it. I got what that character is. Even if it’s a certain color, a certain energy.” And then Altman gave him the part. He did Move and I Love My Wife. He did Richard Rush’s Getting Straight. And then he starred in and produced Little Murders, directed by Alan Arkin, based on the Jules Feiffer play… And then Ingmar Bergman’s The Touch – “I can’t say no to Ingmar Bergman, I want to know if I can act” – which was a meaningful experience for him – to work with Bergman and to talk to Bergman about many things – “In recent times I had seen an article which quoted Ingmar Bergman as saying I was difficult to work with. And that wasn’t true, nor is it true. But Ingmar is no longer living. Fortunately, there was an interview with Dick Cavett when The Touch was going to be released, and I couldn’t attend it, which was a disappointment to us… but Ingmar said on the Cavett show, which is on YouTube, that the day I showed up it was evident to him and his whole family, the crew, that I was a team player.” We led up to his ill-fated project A Glimpse of Tiger. So much interesting stuff – I will try to work on a second part of this interview to dig in deeper regarding all of those movies before and beyond The Long Goodbye…]

EG: The Long Goodbye was like a movie, movie, this was like in relation to movies I had seen growing up. And what with Altman giving me the kind of freedom he gave me, and for to have played a classic character out of time and place, it was like, in a way, a first movie for me…The Long Goodbye was the perfect vehicle for me to live in… I had come back from working with Ingmar Bergman [on The Touch], to do another picture, which was an error. There’s no shouldas… Once I could see that mostly people were in it for mostly what they could get out of it – and I don’t have necessarily a false value – but a great deal of what I could bring to it. You know, become a part of something. And so, that picture didn’t get made. But I started it and I didn’t finish it and I had to pay for it… and it was thought that I was nuts. And I must have been a little nuts in terms of not fulfilling my commitment to a picture…

KM: Oh, this was the project…

EG: It was called A Glimpse of Tiger and it emanated into What’s Up, Doc? which had nothing to do with what I was talking about [A Glimpse of Tiger]. My picture was like The Little Prince in urban American now, and the prince was this young girl, played by Kim Darby. They let me cast Kim Darby and they fought me all the way with Kim Darby and we couldn’t find anyone. And I remember meetings that I had … but that’s a different story… So, then I’m not working. I can’t work and they, being the establishment, without me being examined, they collect an insurance policy based on me being nuts. And I wasn’t. But in terms of understanding what I was doing and what I was trying to do, I didn’t quite know boundaries and limits. I thought I had earned the right to create. I thought I had earned the right to be in charge. We already made Little Murders I could do almost anything and… I had a very fertile potential to produce. I know chemistry in terms of nature and what worked together and there’s nothing more important and therefore, I just need writers… so I had no work. And then David Picker gave it to Robert Altman and here we are…

KM: I read that Altman had people read “Raymond Chandler Speaking”… which brings me to the beginning of the picture with your cat, a famous scene, which I love, and is an extension of Chandler because Chandler loved cats. I read that Altman said the cat is key because you can’t lie to a cat.

EG: Well, sure that was Altman! Altman said to me before we started to shoot, he told me the first sequence with the cat and the food. He said, “That’s the theme of the picture.” And that’s all Altman. It’s all Altman…

KM: And then the line throughout the movie is “It’s OK with me…” which was you …

EG: Altman gave me that freedom. It’s always the way I am. That was the first day. What that reflected to me was, I don’t necessarily know what anything means, I don’t know what’s going on and here we are after having awakened and trying to replace my cat’s food with something concocted. And again, this scene is not in it – the first day of shooting, we went to the CBS Radford Studio because we wanted an office building where a lot of different, like if you’ve got dentists, or a lot of different private eyes, or even Sam Spade at one point – and when I’m there and I say “It’s OK with me” … meaning, like I don’t understand what you’re doing or what any of this means, just don’t tread on me. And think what you think, do what you want to do, but I’ll just go my own way.

KM: It’s such a wonderful refrain throughout the movie…

EG: I had a little house in the beach… and Altman hired a skywriter to fly over my house and write, “It’s OK with me, too…”

KM: Really?!

EG: Yes, isn’t that sweet?

KM: Yes, that’s incredible. Do you also believe that by the end of the film that it’s not OK for Philip Marlowe?

EG: No, it wasn’t. He killed him [Terry Lennox]. No, it’s not OK.

KM: The setting is that present – the early 1970s Los Angeles, which is so much different than now, in Los Angeles, but… in some ways, not entirely different…

EG: No, it’s not different than now. That’s the title for the sequel that I’m still interested in making – It’s Always Now [an adaptation of Raymond Chandler’s story, The Curtain]. The Chandler Estate gave me the rights to (I no longer have them) The Curtain… this [Chandler’s story] was pre-The Big Sleep and pre-The Long Goodbye. The character’s name [is different] and they said I could be Philip Marlowe… The character is much older but he still has the same spirit and the same mind and the same focus… I did a little work with Bob on it, I’ve got a first draft screenplay from Alan Rudolph… It’s a very interesting project, and you can see where The Big Sleep came from…

KM: Working with Sterling Hayden – he’s so raw and touching.

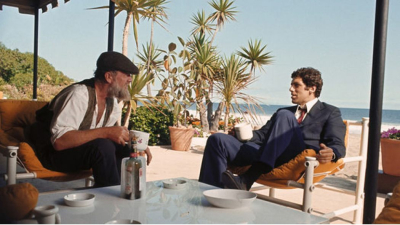

EG: You know the history was that Bob cast Dan Blocker and then Dan Blocker died and it was almost the end of the picture. And then I thought about John Huston, but then Bob cast Sterling Hayden. And I asked to meet Sterling Hayden, I just wanted to sit alone with him. And in a dark room in the house that Bob had been living in…

KM: The house in Malibu…

EG: Yes, which was the Wade House [in the movie]. I was in a room like this, and he had recently come back from Ireland where he had some work with R.D. Laing… and so I knew that Sterling knew that I knew that Sterling knew that I understood him… So, at one point when we were in Pasadena working at the sanitarium where we find Sterling Hayden in that cottage that he’s in with Henry Gibson (you know, that specific cottage was where W.C. Fields lived the last part of his life…) And when Altman would be stressed… Sterling would say to me, I don’t know how he phrased it exactly, but, “Is the old man giving you a hard time?” something like that… And I said, “A little bit.” It didn’t have to do with the work but it probably had to do with my response to what Bob needed, and I’m always looking for something. And Sterling said, “Just vamp.” [And] what does vamp mean? It means, to hold time, meaning, when you vamp with music you hold time.

KM: Sterling Hayden and you … your chemistry together is beautiful.

EG: And the kind of man that he was! That scene where we’re sitting down and [having the drink] … Bob had designed it so that the camera is circling the two of us. And we couldn’t even know whether it would be able to be edited, but I didn’t have any doubt, and I don’t think that Bob has doubt, and so we did that with the aquavit.

KM: And part of it was improvised?

EG: I knew there were certain pieces of information that had to be in that scene so I could help with that [improvising], otherwise it was just about getting to know and see this relationship between these two different generations of men, and that was pretty amazing…

KM: I know you loved Hayden – was Hayden during the whole shoot, working with Altman – was he fine all during the production?

EG: Yes. [Gould nods a decided yes]. He hit me in the ear. When he comes home the night before he goes to sleep and I’m there, the “Marlboro Man,” he hit me on the ear – it really hurt. He really gave me a whop on the ear. Oh my god. It’s there in the picture too. I almost saw stars. Sterling was fabulous. Just fabulous…

EG: Yes. [Gould nods a decided yes]. He hit me in the ear. When he comes home the night before he goes to sleep and I’m there, the “Marlboro Man,” he hit me on the ear – it really hurt. He really gave me a whop on the ear. Oh my god. It’s there in the picture too. I almost saw stars. Sterling was fabulous. Just fabulous…

KM: His frustration, his anger is so palpable, his drunkenness so real, it’s just such a powerful performance…

EG: Oh yeah, I sometimes think about establishing or seeing what it would take to establish a new category, several new categories at the Academy for performances that were not only overlooked, but not recognized, and his would be one.

KM: I like the little touches of old Hollywood in the film kind of living there on the periphery…

EG: Of course! Bob does that in the beginning and the end. And then, the end, “Hooray for Hollywood…”

KM: The security guard who does the impressions, he is so lovable.

EG: Oh, I know. He’s so charming! I wouldn’t have used the car… that was my car… the 1948 Lincoln Continental Convertible. I had won a bet once, and I don’t gamble anymore, as much as I love to win, I hate losing more and there’s nothing I need that I can win… I won the money to buy that car. And Bob used it. I didn’t even charge them for it. But I wouldn’t have used that car. I thought it was sort of obvious, I must say. It was called the Last American Classic. And John Wayne had one earlier. It was green. I gave it to Harrah’s Museum and they re-painted it and it’s there in the museum right next to the car that James Dean used in Rebel Without a Cause… It all connects. You know, it all connects…

KM: The casting is so wonderful and unexpected throughout – two of the main actors had never acted before…

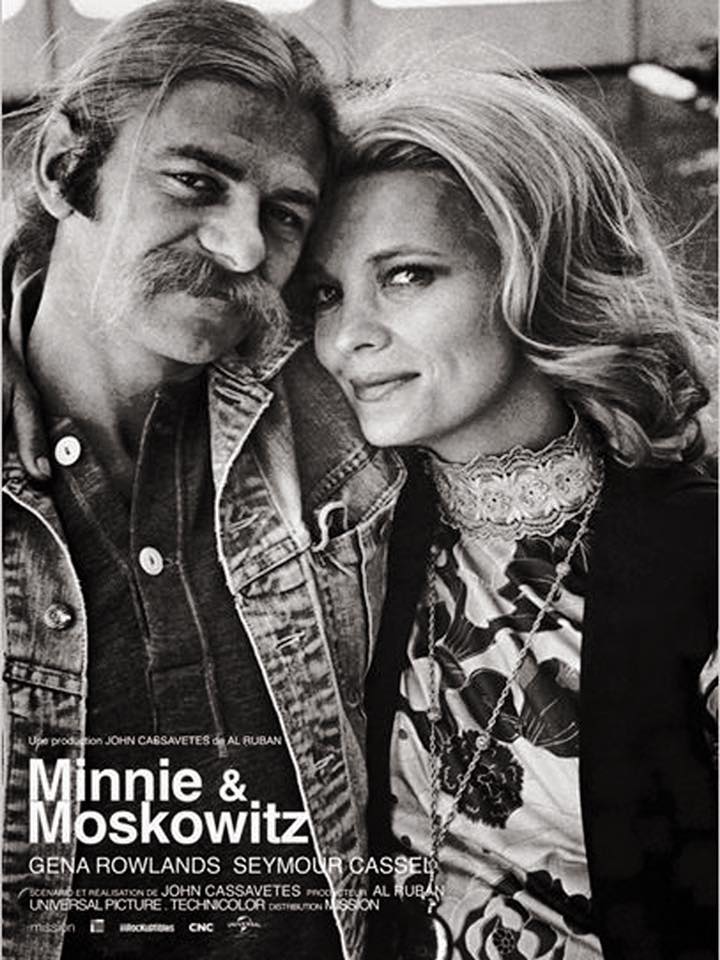

EG: Yes. Jim Bouton. And Nina van Pallandt. She was a singer…

KM: And then, Henry Gibson – this was his first time working with Altman and he was so perfect…

EG: Henry Gibson. Yes, he was great. He was really scary in it. A really scary character.

KM: And Mark Rydell is also so scary in it…

EG: Oh, he was fabulous in the movie…

KM: As you obviously know, Rydell, a director… and he directed you…

EG: Yes, in Harry and Walter Go to New York…

KM: And I read that Rydell and Larry Tucker – who wrote with Paul Mazursky as you also know – that Tucker and Rydell re-wrote the Marty Augustine character …

EG: Larry Tucker and Paul Mazursky – they wrote I Love You, Alice B. Toklas, and Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice. And then they did some other pictures. They did Alex in Wonderland. They were pleading with me to do Alex in Wonderland but I wanted to do Little Murders. And again, not to be sorry… I have no regrets…

KM: And Little Murders is such a great movie! I love that movie.

EG: Me too. I know. Oh, I know. But… I would have met Fellini…

KM: I’m curious about how the movie, the way it was shot, the camera movement, all of that, and how all of the actors flowed together as you were working…

EG: I read Luis Bunuel’s autobiography and there’s a story in it about when someone asked him to do a movie. And he asked, “How much do you have for the movie?” And at the time they said $75,000 and he thought, and then said, “I’ll do your movie for what you have for it, but you’ve got to stay away, I don’t want anyone else there thinking. No one else can be involved. It’s just us.” Do you know what I mean?

KM: And so, was Altman like that on the set – and with you?

EG: He said to me, when he called me in Munich another time, to take over what we thought Steve McQueen was going to do in California Split, he said, “I know if I give you a nickel, you’ll stretch it more than anyone else would consider.” And, well yeah. We want to work, we want to continue to work, but we have to be free…

KM: Did you have the most freedom with Robert Altman? It sounds like you did, of all of your directors you worked with, that he gave you that freedom…

EG: Well, I took it. I took it… Altman needed so much freedom to do what he did. I breathed it in. I took it… On The Long Goodbye, he told me I scared him. In terms of being free, and in terms of adapting to where we were at. Because even with the drowning scene and having waited for the high tide, Altman said to me, “Do you think we can do the two days work in one night?” Being that the first part was Sterling [when, in the movie, he’s walked out to the water], and the next was me running down, and the next part was waiting for the high tide, and then me going in there and coming out – and I nearly drowned. I literally nearly drowned… I had been playing basketball all day, and then I ran down to the beach several times… I thought, “You can’t go down, Elliott, there’s no one here to bring you back up.” And I was able to bring myself up and be able to go to her [Nina van Pallandt] and she was acting right there. She did great, she was perfect. And then we had to do it again, and I was really scared. And so, I could act a little more. I didn’t realize this was the mother ocean. And, I was aware that I was out of control, and if I went down, I was really close to drowning, because there was no one there with me… And I said, we could do it. Because I might have had shots with the sun coming up – in the scene where I talk about Ronald Reagan and throw the bottle of liquor – and I can see that people are lying – the police are playing parts, and she’s lying. And also, something interesting, if you want to look at it and analyze it, that Altman gave me all of that room, you know, all of that room. And … we did [the scene] three times… and we could have done it [again], but Altman came to me and said, “I’m tired. We can’t do it.” And I was all ready to do the two nights together. But it worked. But I would have loved to have seen sunrise in it. I would have loved to have seen the light change. Using light in relation to our mind.

KM: The movie is referenced in other films, you see the influence – like The Big Lebowski and you feel it in Inherent Vice… you see how much people return to the picture…

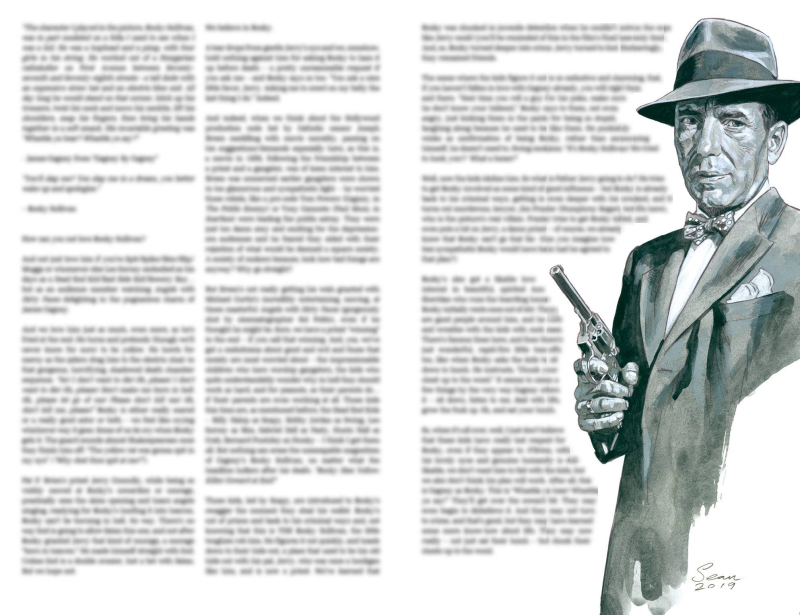

EG: It’s an American jazz piece… Sometimes I’ll study a generation later [in life]. Like I started to study High Sierra, and [John] Huston wrote that… Yeah. Ida Lupino. And I remember seeing it at the time. Now that I understand myself, and I could see through it. Bogart was fucking perfect… You talk about things that hold up. I mean, I watched Casablanca [again], not to be sentimental. I don’t want to deny it – if it touches me, it touches me. It means I’m still living.

KM: But no one’s ever been able to do you – you are so one-of-a-kind, I don’t think anyone could really emulate your performance, there’s no one like you.

EG: I would rather not ever go there… I should really go out and find all of the books on tape that I did [reading] Chandler, I think I did all of them – but I don’t want to go there. I find a personal identity in that. But it’s very hard to do. Because you have this character. This guy. I mean, he’s, it’s, a unique character. There’s no ego there…

KM: No, and it’s not a stereotypical type of masculinity either…

EG: Well, whatever masculinity is…

KM: And how Marlowe talks to himself, your interior monologue that you’re vocalizing…

EG: Always! Don’t we all have that?

KM: There’s such alchemy with this picture. Did you know you were making something so masterful, so magical while you were doing it?

EG: No, no you can’t… And sometimes we hope for things, and we don’t necessarily know what we hope for. We hope to do well enough to validate continuing to work. I’m sure that there have been some pictures as far as seeing some magic, or seeing something fuse; seeing different ideas fuse… But the idea… it’s Altman. It’s Altman. It’s Altman’s chemistry. And of course, me, being in the right place at the right time … It’s so close to me. It’s so close. It really is. I mean, again, Bogart was sublime. Dick Powell – he’s interesting, I look at some of his work, he’s a very fine actor and director and smart business man. And then you had several people, and even afterwards, like Robert Mitchum, and I love Mitchum… But, no, no, I’m glad Bob and I made the one. And… it breathes.