“Wally Reid was a 180-pound diamond…”

–Cecil B. DeMille

Wallace Reid loved cars. When not working in pictures, the silent screen star would speed through Hollywood in a choice automobile, wildly tearing up roads in anything from a Marmon Coupe to a Stutz Convertible. Not just a well-heeled showboat Reid actually understood cars. He knew how to work on cars, he comprehended their mechanics and appreciated their beauty. Before his racing pictures, before traveling to Hollywood, before even working at Vitagraph, Reid wrote about cars for Motor Magazine, covering races, attending car shows and test-driving new models. As a famous actor he made friends with racecar drivers and entered races himself. He was fearless and he was reckless. For those he delighted with his rakish rapidity, there were others he horrified. His abandon was legend. He reportedly crashed his Marmon into a family while hurtling along the Pacific Coast Highway, killing a father and seriously injuring a mother and child. His passenger, Thomas Ince, suffered a broken collarbone and internal injuries. Wally was fine. He was well connected, well liked and lucky. D.W. Griffith bailed him out of jail. He wasn’t lucky for long. In less than ten years the star of The Roaring Road would be dead. His beloved Marmon didn’t do him in. Morphine did.

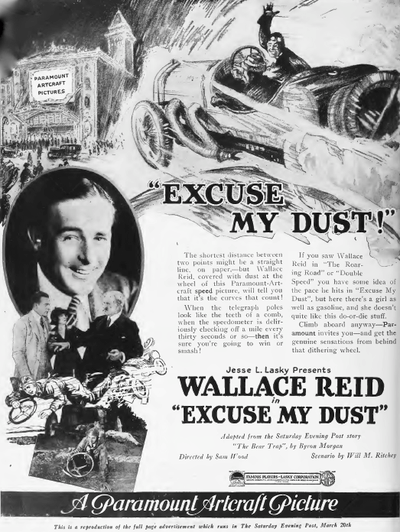

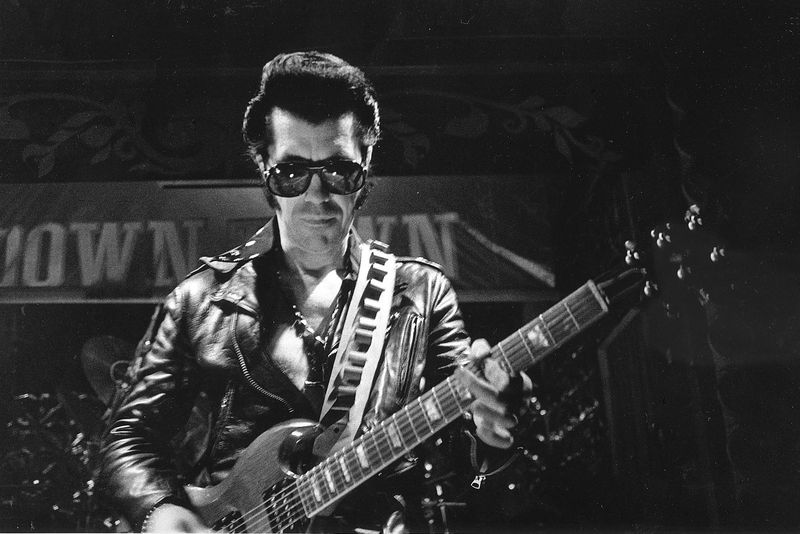

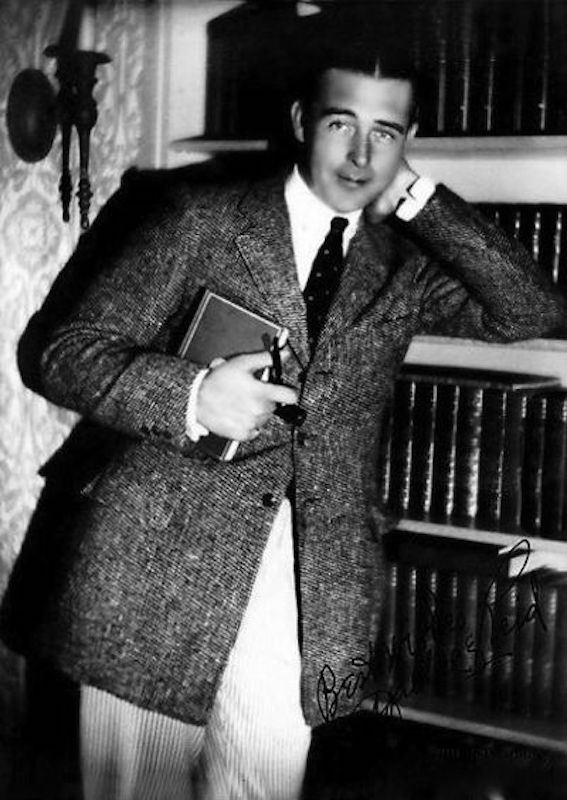

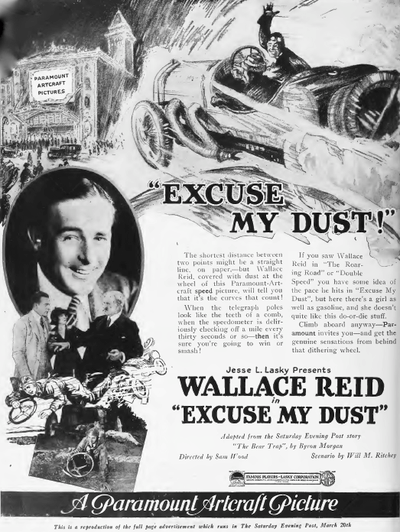

An enormous star of the Silent Screen, Wallace Reid or, “Wally,” as he was affectionately called, isn’t talked about much these days. His 200 plus pictures, many lost or tough to find, are rarely seen, his troubles occasionally discussed; many don’t even know who he is. A big enough name to rival Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks and Charlie Chaplin, the "screen's most perfect lover" was beloved by fawning women, admiring men and awe-struck kids. He was cool. He made soft collars fashionable, influencing men to abandon their stiff, detachable neck stranglers. Young, not-yet-famous Clara Bow once waited eight hours to see Wally’s personal appearance in Brooklyn. He starred in Cecil B. DeMille pictures including, Carmen (1915), Joan the Woman (1916) and The Affairs of Anatol (1921), worked with Dorothy Gish, Gloria Swanson, Geraldine Farrar and Bebe Daniels, popularized racing pictures including The Roaring Road (1919), Double Speed (1920), Excuse My Dust (1920) and Too Much Speed (1921); the inventory of pictures and collaborators are too extensive to list. Tall, well built, handsome, he was adept with drama, romance, comedy and action, making him a major moneymaker for Paramount/Famous-Players Lasky and one of the first movie stars of the silver screen. He was also one of its first dope casualties.

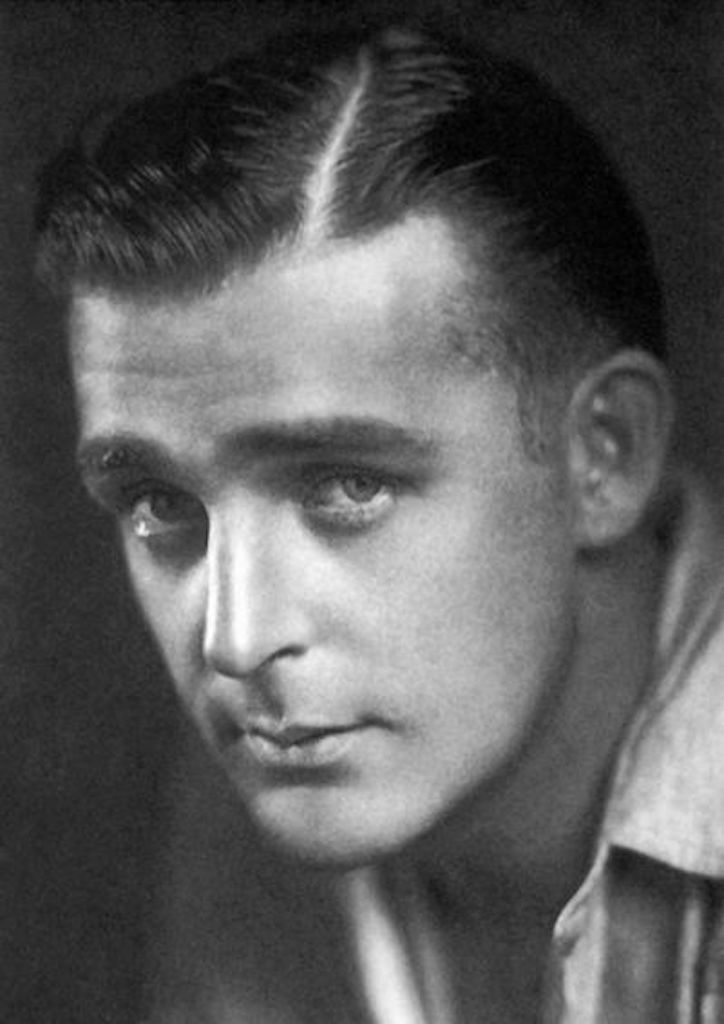

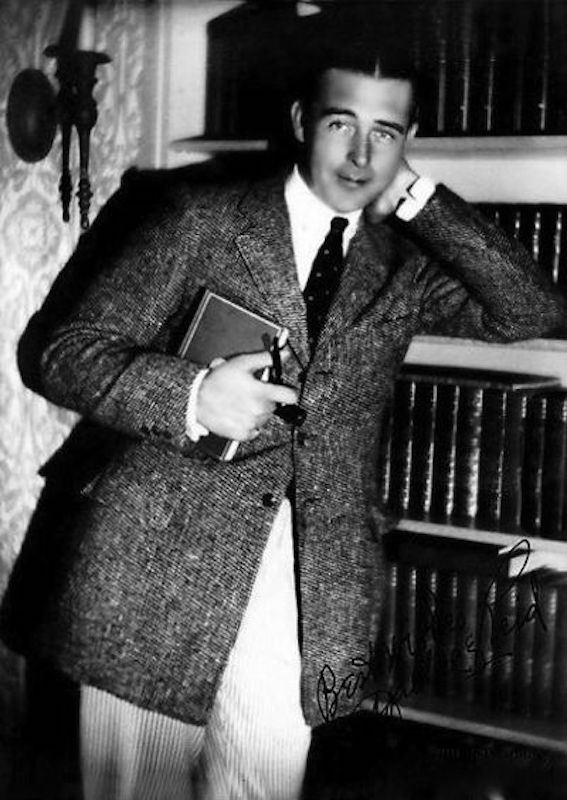

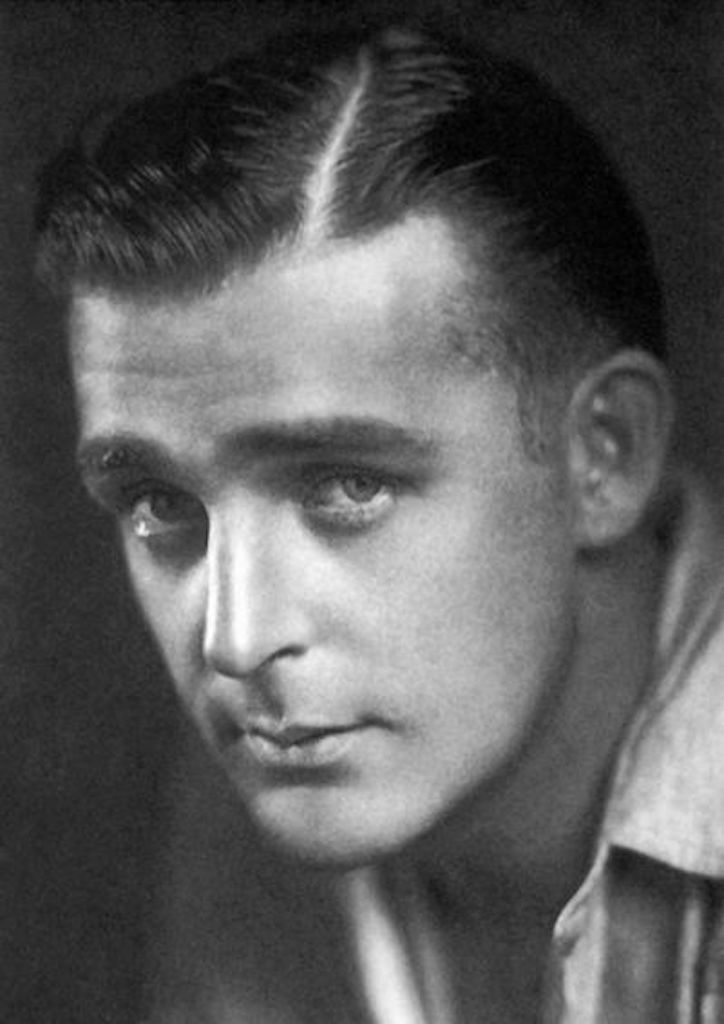

In photographs, he’s immediately handsome in a boyish, everyman sort of way. One wonders if he would pop on screen the way Douglas Fairbanks, John Gilbert or Rudolph Valentino had. But in the few starring roles I’ve seen, he does stand out, albeit with different effect. He’s relatable. Watching him sensual and intense in Carmen opposite Geraldine Farrar or almost erotically explosive in his smaller but unforgettable part in The Birth of a Nation, you get the sex appeal right away. He's timeless. I could picture him a heart-throb today. In pictures like The Roaring Road, the pre-McQueen real-life gearhead was thrilling to viewers. Utterly American, he was the adventure-seeking dream, affable, a man’s man. But there was something soft and lost in his eyes; a vulnerability that wasn’t simply effete, more like susceptible. Though intelligent, well read, outdoorsy, musically talented (he could play any instrument and reportedly kept neighbor Rudolph Valentino up with his saxophone) and creative, Wally was modest, generous to a fault and suffered low self-esteem. He didn’t always feel like a man’s man. When inscribing a photo for his friend, the journalist, screenwriter and novelist Adela Rogers St. Johns, Wally wrote: “Just another so-and-so who never got into uniform except when he put on his greasepaint.”

Reid entered the movie business during its exciting, embryonic time, when motion pictures were an evolving art, full of invention and experimentation. An enthusiastic Wally worked, watched and learned alongside some of the great pioneers: Griffith, Dwan, DeMille. Studying Reid’s history is studying the inception of movies – all of it – the developing technology, the lengthening of films reel by reel, the beginning of the star system, the growth of the studios, the arrival of watchdog Will Hays, the press, the fans, the scandal. Surely, the first flushes of scandal were hard to wrap one’s mind around. With fame coming so suddenly and with such unexpected fervor, the new stars had to quickly learn navigational skills never before imagined. There was, as they say, no road map. That mixture of adoration and scrutiny, the money and the mania, it had to have muddled the mind, creating great highs and great lows. Those drunk with celebrity one second could be depressed and paranoid the next. Drugs settle the mind, sooth the nerves and at their most blissful, double your pleasure. Smoothing out that rocky road, who needs a map?

The two Reid biographies, E.J. Fleming’s “Wallace Reid: The Life and Death of a Hollywood Idol” (McFarland, 2007), and David Menefee’s “Wally: The True Wallace Reid Story” (BearManor Media, 2011), take you through this fascinating period with a compelling leading man; a young man who had no idea how “live fast and die young” emblematic his story would become. Both books were essential to researching this piece and proved passionately written page-turners by writers who made all of their exploration and analysis come to life. Born in 1891 to a theatrical family, both successful and scandalous (as reported in Fleming’s book, his actor and playwright father was charged with rape in 1887, a newspaper calling him “Hal Reid the Minneapolis Fiend”), Wally had little desire to work in front of the camera. While at prep school, young Reid was intent on becoming a surgeon. Nevertheless, he was seduced by cinema, excited about writing and directing.

According to Fleming, Wally worked as an “assistant director, scenario writer, cameraman and utility man” in Chicago under William N. Selig where he wound up appearing in numerous pictures. His first credited role was in The Phoenix in 1910. After that came Vitagraph where he wrote, directed, cranked camera and played violin or viola on set. Against his filmmaking desires, he also acted. After a failed engagement, he ventured to Hollywood and again worked with Selig and moved on to the West Coast Vitagraph. He also worked with his mentor, pioneer Allan Dwan, at Dwan’s “Flying A” company, and went with him to Universal. It’s tough to keep track of or to know just how much Wally accomplished during the infancy of cinema, he seemingly did it all. But he was too good-looking to stand behind a camera for long. Once he stunned audiences in Griffiths’ Birth of a Nation (1915) as the wrathful, shirtless blacksmith, that was it. Wallace Reid was a movie star.

I first learned of Reid as one part of the early trinity of Hollywood scandal. The trials and unjust destruction of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle (who was cleared in the case of Virginia Rappe but the reputational damage was done), the mysterious murder of William Desmond Taylor and the All-American matinee idol turned addict, Wallace Reid. His fate was sealed by what is usually understood in figurative terms, a train wreck. For speed demon Reid it was horrifyingly literal. While traveling to their Oregon location for the James Cruz picture, Valley of the Giants (1919), Reid and company experienced a near-catastrophic crash when their train fell off a bridge, rolled down 15 feet and landed on its side. Wally was seriously injured, suffering a deep laceration to his skull, a gash in his arm that cut to the bone and severe injury to his already weakened back. It was a harrowing, bloody calamity that would, today, stop production on any motion picture. Menefee wrote: “Alone and in the middle of nowhere, they were without any outside help… For the next twelve hours, Wally used his medical skills to administer to those who were injured… Rescuers finally arrived, but only after the injured had languished in isolation for half of a day." Wally, most wounded, was one of the last to be treated. He was soon back on set.

To ease the excruciating pain during filming, Wally was given morphine — a lot of morphine. And so it began. Shot up with the opiate for his agonizing injuries, it was administered whenever needed. Swiftly, he was hooked. And, as the story goes, the studio kept him good and smacked up. Needing their All-American cash cow to work at his same level, to continue to churn out pictures fans stood in line for, junk was necessary. In 1919 Wally had eight movies released. Mary Pickford had two. Whether or not the studio supplied him with endless drugs is not absolutely proven, and from reading both biographies, it’s clear that when his addiction worsened, Wally scored his dope on his own.

Wally was well-liked around town and, like many actors and addicts, gifted at concealing his problems. When rumor was strong, the studio hired a doctor to live with Wally for two weeks. Wally either bravely abstained two weeks of hell or sneaked his doses, manipulating his watchful houseguest. The doctor reported back to his bosses with not only a clean bill of health but with a veritable boy crush. He wrote, “I don’t know anyone else I could live with like Siamese twins for two weeks without wanting to murder, but he is unquestionably the nicest chap I’ve ever known.”

Wally could not and would not stop. As chronicled in Fleming’s book, it was work, drugs, parties, affairs, a mysteriously adopted three-year-old daughter and eventually, unavoidable scandal, with Wally’s drug dealers getting arrested and newspapers writing items alluding to or frankly discussing Wally’s drinking and drugging. And yet, he continued to work. Eventually, his diminishing frame, loss of teeth, moodiness and deteriorating beauty were becoming all too evident. The fact that he was even cast in Nobody’s Money directly after being unable to stand during the filming of 1922’s Thirty Days is horrifying – the studio was going to use their asset, and Wally wasn’t giving up, even on the brink of death.

In Kevin Brownlow’s 13-part documentary Hollywood: A Celebration of the American Silent Film, then assistant director Henry Hathaway tells a heartbreaking description of Reid’s last day on Nobody’s Money, Reid’s last day on any movie set: “He sort of fumbled about, and bumped into a chair, and then just sat down on to floor and started to cry. They put him in a chair, and he just keeled over. They sent for an ambulance and sent him to the hospital.”

Wally was taken to the Los Angeles sanitarium of Dr. C.B Blessing, which treated addicts via a controversial method called the “Barker Cure.” As told by biographer Fleming, Blessing followed the remedies of Dr. John Scott Barker, whose Oakland drug treatment facility was raided “numerous times.” Fleming wrote, “His most famous client, actress Juanita Hansen, said the ‘cure’ consisted of a cocktail of unidentified pills and medicines and a rigid diet ‘to extract the poison that remained in my system.’ Rumors abounded that the pills were just replacement drugs that kept the addict off one but hooked on another.” Wally stayed there for six weeks. When that didn’t take, his wife placed him in a private sanitarium where he dried out in a padded room. He wasn’t improving. He was, in fact, dying.

One thing curious about Reid’s story is just why he was dying. Hearing about Reid’s tragedy, one would think the man suffered a fatal shot of morphine and overdosed after various cures. Cold turkey is terrifying and dangerous, but you can live through it, particularly at 30 years of age. Adjusting your life and resolving the need for dope is the long-term challenge. Reid never even got that chance. Instead he wasted away, with kidneys failing him, a respiratory system, shot, fever, flus –a nightmare. Overdose would have surely been a welcome relief from such wretched hell. Both Reid biographers state that Wally wanted to go out clean, that he’d rather die than seek comfort from the elixir that produced his demise. Drugs and drink will lower your immunity, and Reid’s use was extreme, but after reading of another one of Reid’s earlier cures, I wondered if it contributed to his rapid decline.

Called the “Crebo Method,” the regime, as Fleming describes, “was a daily mix of injections, enemas, and pills with crebo, curare, ephedrine, luminal, emetine hydrochloride, philocarpine hydrochloride, adrenalin, avertin, and adreno-spermine. Curare was an interesting choice, a plant compound used in South America as an extremely potent arrow poison… Death results from asphyxia by paralyzing skeletal muscles and depending on the animal’s size takes from seconds to 20 minutes.” Curare?! If that’s not enough to raise an eyebrow, these disturbing mixtures were injected directly into the chest. The side effects are a list of horrors: every kind of nervous symptom, exhaustion, twitching, cramping, thirst and dysentery are among the trauma. Usually these treatments were undertaken in a clinic. Wally performed all this at home.

He wasn’t alone. His wife, actress and, later, filmmaker, Dorothy Davenport was by his side. Dorothy, whom Reid married in 1913 (back when he was known as a director at Universal instead of an actor) is an intriguing character herself. After Wally’s death, the actress became something of a pioneer for both female directors and exploitation pictures, often crediting herself as “Mrs. Wallace Reid.” Her earlier work contained tonier collaborators, including the 1923 drug scare picture Human Wreckage, starring herself and Bessie Love. Dorothy co-produced the now lost film with Wally’s crash survivor, Thomas Ince. The next picture she produced was 1924’s Broken Laws (based on an original story by Reid friend, Adela Rogers St. Johns) in which she stars as an overbearing mother whose son becomes a spoiled jazz head and reckless driver on trial for vehicular manslaughter. Considering her relationship with Wally’s mother, this was an interesting social ill to sensationalize. She moved on to directing exploitation pictures including, Linda (1929), Sucker Money (1933), Road to Ruin (1934) and The Woman Condemned (1934) and, for a spell, before she lost money in a lawsuit involving her white slavery film The Red Kimono (1925), she owned and ran a Los Angeles apartment building. Purchasing the place in 1930, she called it “Mrs. Wallace Reid’s Casa de Contenta Apartments.” One of her tenants was Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle.

Her fervor started before Wally died. When Wally’s use became too obvious to ignore, she went to the already pouncing press to discuss not only her husband’s plight but the evils of narcotics. Reid didn’t see shame in Wally’s misfortune and appealed to an empathic public. She also changed stories, a lot, and comes off as unreliable — oddly, both frank and in denial. \

She must have suffered guilt over enabling him (though no one used that term at the time). She was probably angry too. And, so, turning to more exploitative measures, she's a controversial figure.

While Wally struggled, Dorothy let the world in on his torment. Reported in Menefee’s book, the distraught wife told the New York Times intimate details: “He thought he would die the other night,” she said. “He was so brave about it, poor boy. For three nights he had expected to die. He isn’t afraid to die, but he wants so much to live for Billy and Betty and me,” referring to their son and adopted daughter. Mrs. Reid, in describing his condition just before the present breakdown, said that he wept and said: ‘How did I happen to let myself go? Why couldn’t I have stopped long ago? I thought I was so strong; I thought I knew myself so well; I can’t understand it.’”

Reid was still young. Just out of his twenties. It’s not surprising he was baffled by how deadly his addiction became. Like the Marmon that he cracked up, he was confident he could control it at any speed. And when he lost control, he even thought he could outrun it. But not by the end. He finally collapsed and, on January 12, 1923, he was dead. He was 31.

In Fleming’s book, Wally is quoted from a picture magazine interview, revealing more about himself than he probably realized: “I love to speed. If I always drove myself, I’d probably spend half my money on fines for breaking the road laws… Whether speeding down an open road or through the air, I feel a surge of blood through [my] veins that prompts [me] to ever-increasing speeds.”