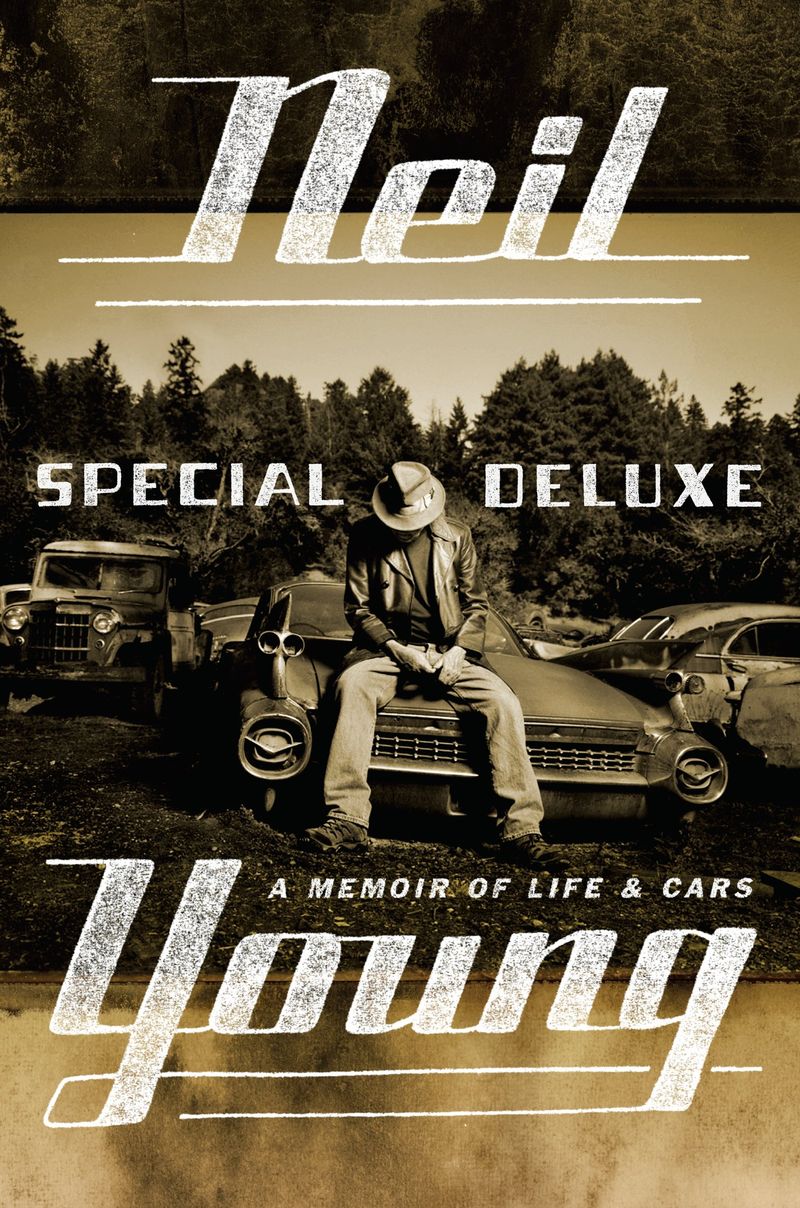

Journey Through the Past: Special Deluxe

“We were beginning to feel that the Continental had a soul, memories of the past and feelings about where we were going and what we were doing.” – Neil Young

When I was nine-years old, my mother rambled around in an old pine green Dodge station wagon. It was a big honkin’ thing, it seemed so out-dated, the back-end smashed, the seats an obnoxious green (everything in that car was green) the benches all tore up, wrapped together with silver duct tape so that when her purse spilled, which was often, dimes and quarters and lipstick tubes would get stuck and lost forever in the upholstery. She called it “The Green Bomb,” I later deemed it “Divorce Wagon" because it seemed like the dad-is-gone car. I don’t even remember the car from before. I was too young when they divorced (5) and I never processed it properly. In my mind, it magically showed up once my dad left (or she left him), though it must have been the family wagon. But there it remained – the car where mom donned big sunglasses and listened to songs on a tinny radio and was probably crying or raging or weirdly content – all over the place. Like the groceries rolling around the back seat when she rode the break, driving us kids insane. I don’t remember my Dad ever even being near that car. I hated that car.

Now, I’d kill to have that car. Once mom re-married and we moved from old-car-cool Bainbridge Island, Washington where no one cared about old ripped-up station wagons, neighbors loved vintage cars (and we had about five cars there anyway, including an MG, A VW Square-back, a motorcycle and my Uncle’s Lotus) to, what I viewed, an uptight little college town in Oregon, where cars were boring and newer (they all started looking like suppositories to me), a place where I had to make new friends who might just judge ripped seats and busted-up back ends, I could feel myself sinking into the floorboards whenever we picked up the infrequent play date in that thing. I turned against that car. I didn’t care to fit in there, I just loathed that the car used to be just fine. Now it was this rambling eyesore to, what I perceived, a bunch of jerks. That car represented something torn up in life. I just wanted her to get RID of it.

And then one day my mom came home and surprised us all: A gold Mazda (I can't remember the model). What?! I was so thrilled by this sexy, new car, I jumped up and down: “It’s so shiny!” And then, I asked… "So, what happened to the Dodge?” Mom replied, cheerfully "Oh, it's gone." I was suspicious: "Gone? You sold it? Someone’s gonna fix it up?" My mom said, laughing a little, almost sing-songy: "No, no, no. It's going to be crushed.” Suddenly, I was horrified and, then, filled with guilt. Surely I’d felt empathy in my little life before but this felt like something new, something I was complicit in. This is all my fault. I wailed, “The Dodge is all alone? It's all alone in some crusher? It's going to be killed?!!" My mother kept saying, annoyed, "It's just a car, Kimberley. It's not going to die." I protested, "It IS going to die. They're killing the car!” I continued on, awash with crushing remorse: “I was so horrible to that car! I feel so bad for the Dodge — alone. We have to save the car!”

I started to cry. And I couldn’t stop crying. The car became a person, it had feelings and I pictured it entering the crusher, knowing how much the family hated him, cold and alone. And now he was being upgraded with this gold… slut. What if dad does the same thing? What if they don’t get back together? I know mom’s married, but maybe they’ll get back together anyway? I became so incensed with the tacky gold car that I yelled at the car, "You’re so full of yourself!" and then ran inside and cried some more. I mourned that green Dodge for an entire week. A full fucking week. Maybe more. I never liked the Mazda. My mother thought I was insane. I don’t think so. I needed more cars in my life (which I made sure of here and here). And I just needed Neil Young in my life. He did come, later. Thank god. In tough times and wonderful times and magical times, many times marked by cars. Many times in a car. On the road. From the hot desert of Joshua Tree to icy Winnipeg, Manitoba, Young's last city he lived before he drove to California. Young is always felt. I remember the first time I saw the aurora borealis in Gimli, MB. I was so stunned, it was so beautiful, and I could only hear it in my mind the way Young so uniquely and melodically phrases it in "Pocahontas": "Aurora borealis, the icy sky at night…

“Only love can break your heart” but Young knows just as I do, just as many others do, so can cars. With his book, one of my favorite memoirs, “Special Deluxe: A Memoir of Life and Cars” he anthropomorphizes every single car in life from childhood until now. He even paints in watercolor, charming, impressive pictures of each one. It’s all so touchingly detailed, lovely and bittersweet, and then both revealing and mysterious, like Neil Young himself. (Stay with me here, but there's even a touch of Robert Walser in these accounts, the micro memories, and Young's enigmatic writing manages to convey something more revealing than perhaps even he imagines). Cars carry you on adventures and disasters and they can let you down, but you also let them down. I only wish auto enthusiast (if that’s even the right term for Mr. Young, more like beautiful obsessive, an auto-erotic) had been present at that past scene to tell my mother that I wasn’t crazy.

As he writes about his 1941 Chrysler Highlander Coupe, purchased in Malibu in 1975, which he loved, but never fully restored, he cited this reason for it’s disrepair, a reason full of regret and maybe even an excuse: “I don’t know why. It’s hard to understand, but somehow I think it has to do with Vietnam… Perhaps I should have not bought it and just left it alone and maybe someone would have fixed it up. Right now it is a struggle, a story incomplete, an empty feeling. I have to do something about it.”

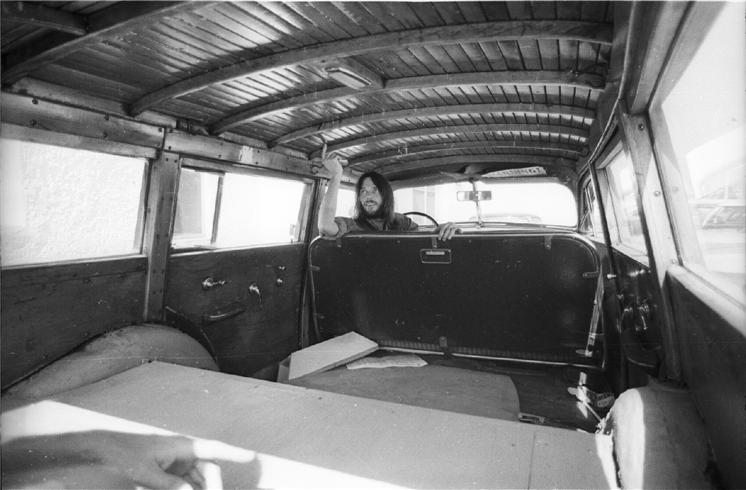

Young’s book is incredible for chronicling nearly every car he’s known, owned, worked on, didn’t work on and then some, from his parents' 1954 Monarch Lucerne, to his various Hearses, one famously named Mort, where he’d haul his equipment around as a young musician and famously drive from Canada to Los Angeles, breaking down on Sunset Blvd, to his 1957 Corvette (a great car to speed around his new home in Laurel Canyon) to a 1951 Wily Jeepster, to a 1954 Cadillac Limousine (named “Pearl”)… Listing all of the cars would take forever, but Young’s owned them and loved them and his gear-headedness is so open and expansive, it’s impressive and passionate. He’s not one of those annoying classic car types – the ones who cherry out a badass muscle car or do the easiest thing in the world: Buy an old Mustang – he seems to love them all, find something curious and soulful about a car.

The slick and the fast, the rambling heaps, the ridiculously enormous family sedans from the 50s all have equal importance and appeal. And, as the chapters illuminate, each car has a memory attached, written with vivid, at times, dream-like detail. Cars drive in and out of his life, underscoring all of the changes and upheaval, some sweet, some exciting, some rock and roll, some down home and family and some very sad. Cars even help him become more ecologically conscious. He loves all of his gas guzzlers, but grows increasingly concerned about CO2 emissions, hence his interest in driving with renewable fuel (like his 2000 Hummer 1) and then, his now famous fuel efficient LincVolt, a 1959 Lincoln Continental converted into a hybrid demonstrator.

And then there’s divorce.

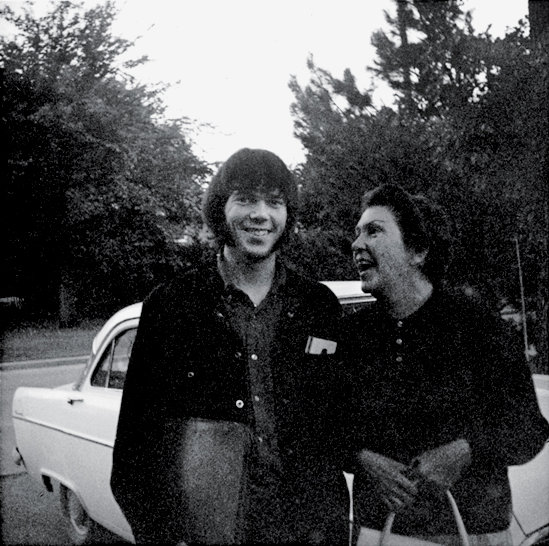

Some of the most moving moments in the book come from Young writing about his parents' divorce. What’s with cars and divorce? Do all of us children of divorce have a car attached? In a chapter covering his dad’s late 1950s Triumph TH3, he remembers his father leaving his mother (with a letter) and that his father was, in his way, telling him about the departure before it happened while driving in that car. “I knew it! I knew it!” little Young exclaims after his father ditches mom. His mother asks, “You knew what?” and then he proceeds to tell her about their car trip. His mother cries and, as Young writes, “I just held on to her.” The memory becomes more painful:

“A few days later, I came home from school and found Mommy in the driveway in front of the garage. She had her record collection out, a big pile of 78s from a couple of boxes. At first, it looked like she was organizing something. But Mommy was crying now, taking out each 78, looking at it, and breaking it on the cement driveway. That was one of the saddest things I have ever seen. I try to block it out of my mind. Just a late afternoon, sun getting ready to set, and there is this picture of her crying and breaking each record, making a little comment with each one.”

What a heartbreaking recollection. And from car trip to house to garage to driveway to… music. It all swirls together in Young’s evocative memoir. When discussing his 1959 Lincoln Continental, his “most outrageous car of them all” and the one he used in his Bernard Shakey-directed movie Greendale (the car that would become the “LincVolt”) Young reflects in the relative present time (the late 2000’s), driving through a lonely Las Vegas with his partner in Shakey Productions, Larry Johnson, discussing the “empty lots, as well as a huge dark old hotel that was no doubt about to be blown up… The giant building where Elvis had played his first Vegas shows. Such was the way of progress in Las Vegas. Out with the old and in with the new. “

Touchingly, Young wonders how the Continental might feel about this ever-changing Vegas landscape, “rumbling along, taking this in, no doubt noticing it was much older than that aging hotel, now slanted for demolition.” The directness and mystery of Young is all over this book, making it, sometimes, as affecting as his music. When he turns back to both the car and to himself and then, states something so obvious, it takes you aback with its frank emotion, the way a lyric like “Do you think of me and wonder if I’m fine?” does from “Journey Through the Past” (that title and song, is damn nearly what this book is all about).

Young writes, “We were beginning to feel that the Continental had a soul, memories of the past and feelings about where we were going and what we were doing. Spending a lot of time with a car can do that.”