Just Waitin’: The Last Picture Show

My piece published at The New Beverly.

“Of all the people in Thalia, Billy missed the picture show most. He couldn’t understand that it was permanently closed. Every night he kept thinking it would open again. For seven years he had gone to the show every single night, always sitting in the balcony, always sweeping out once the show was over; he just couldn’t stop expecting it. Every night he took his broom and went over to the picture show, hoping it would be open. When it wasn’t, he sat on the curb in front of the courthouse, watching the theater, hoping it would open a little later; then, after a while, in puzzlement, he would sweep listlessly off down the highway toward Wichita Falls. Sonny watched him as closely as he could, but it still worried him. He was afraid Billy might get through a fence or over a cattle-guard and sweep right off into the mesquite. He might sweep away down the creeks and gullies and never be found.” — Larry McMurtry’s novel, “The Last Picture Show”

Some of us walk through life as the leading players in our movies. Memories and real life melodrama can intertwine in our minds like our own personal photoplays – we make pictures every day. We see this online, shared photographs and videos, creating story, mystery and art, and sometimes narcissism and pleading. But some of us also do this when we stop for a moment and put away that camera or phone, and we’ve done this ever since feature films have appeared in theaters. Pictures started moving and we starting moving our own pictures. Not with a camera but with eyes and minds – and we still do. Flickering through our brains like vivid Technicolor reminiscences or black and white chiaroscuro, our movie minds also project cinema out into the world, eyes scanning surroundings like cameras, hearts hopeful for something cinematic and exciting to create our own big screen stories. Movies can seep into our souls so much that we often feel we’re walking in a movie – real life should be like a movie – we think. Life can be lonely, a vast expanse of time, experiences behind us, experiences ahead of us, and when we stop to take a look at our environment, a forlorn feeling can flood our thoughts through the most everyday things: out of a car window during traffic, listening to a song, in crowded cities, staring down endless roads and observing barren landscapes. Many of us will be stricken, if even for a minute, with a void or an ache or, to quote Peggy Lee, “Is that all there is to a fire?” Though we study movies for all the reasons people essay and critique them, watching movies can fill and fuel that fire for 90 or 120 minutes or more, an all-enveloping escape, enclosed in dark rooms transported by that large screen. So can transferring those images onto real life, imprinting and even blurring our reality.

There are many passages in Larry McMurtry’s novel The Last Picture Show that exemplify the merging of movies and real life, illustrating why it was so well-suited for Peter Bogdanovich’s tender and heartbreaking big screen adaptation. In the novel, which takes place in 1951 (the 1971 movie does as well), the high school senior protagonist Sonny, admits his affair with an older, sad and married woman to a waitress he’s fond of: “‘Ruth Popper?’ she said, amazed. ‘How do you mean, Sonny? Have you been flirtin’ with her like you do with me, or is it different?’ ‘It’s different,” he said. ‘It’s… like in a movie.’”

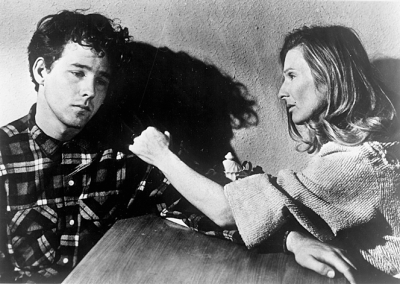

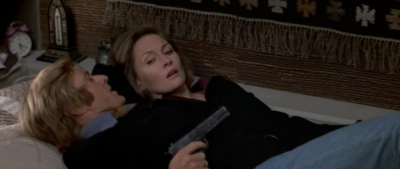

That Sonny really is having an affair with Ruth Popper, and one that becomes complicated, raw and emotionally messy to the point that she frightens him even as he desires her, makes it a hopeful yearning on his part – that it’s like a movie. It’s not, not with any kind of glamour or “suitable” romance, but in its own heightened way, of course it is. Peyton Place or a Douglas Sirk masterpiece, though Bogdanovich and McMurtry do not frame it that way. (The picture feels both New Wave and classic, Bogdanovich knowing his Ford and his Hawks and also something less easily definable, then and even now.) But Sonny gets a thrill and peculiar love from Ruth and eventually they don’t care about their audience – all that talk and the looks in the town – everyone knows. And Ruth is nice to kiss. Much nicer than his first disagreeable girlfriend. Earlier in the movie they do some heavy-petting in the theater and Sonny’s eyes are fixated on a close-up of beautiful Elizabeth Taylor, not his date. In the novel it’s Ginger Rogers and he envisions her naked. In Bogdanovich’s version (co-scripted with McMurtry), we can only think that’s what Sonny is thinking. We don’t doubt it.

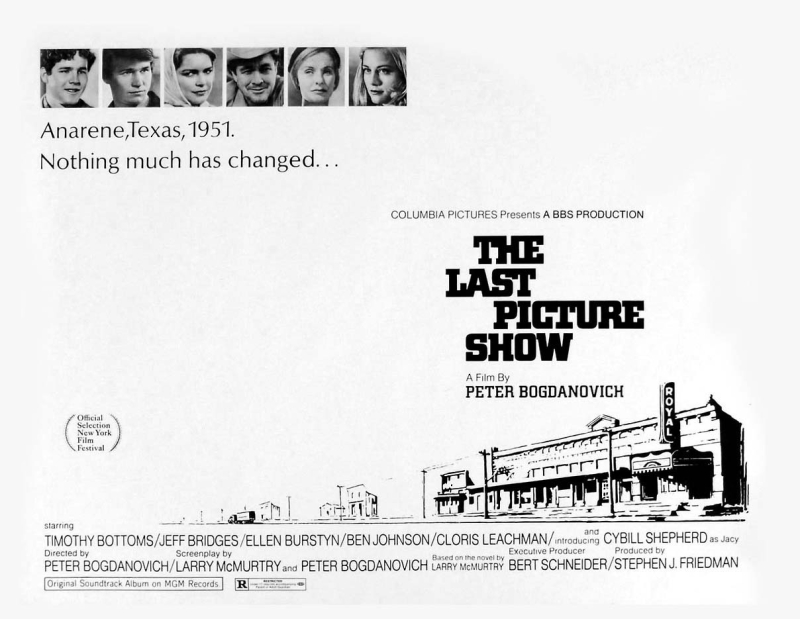

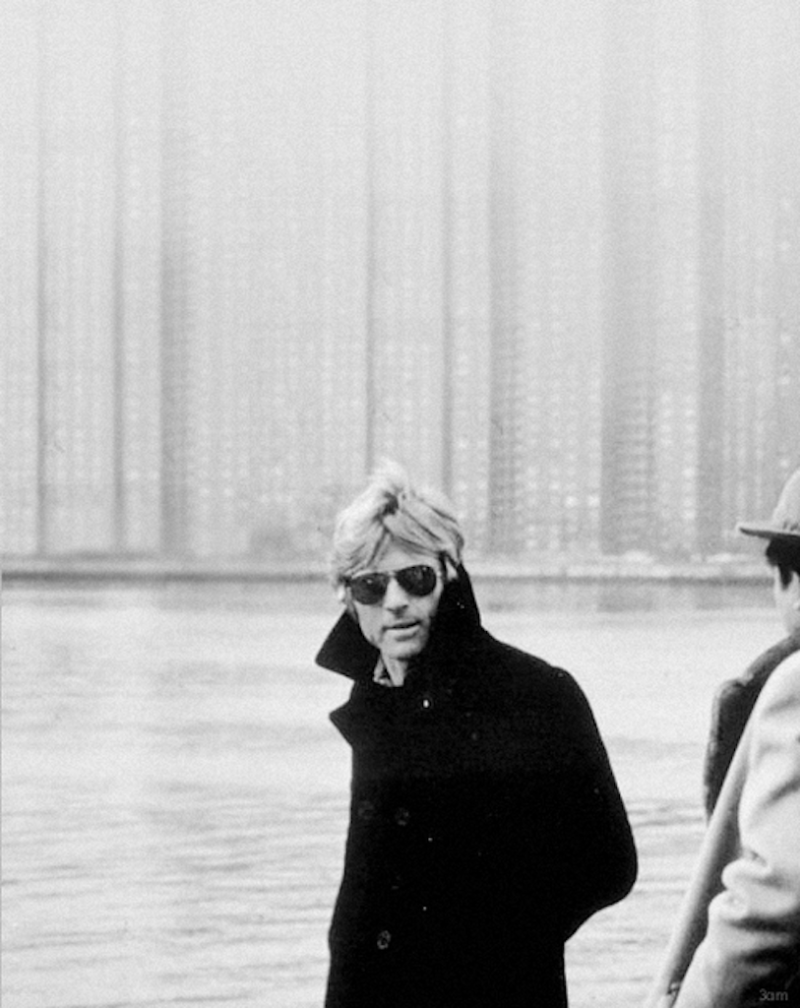

A perfect place for thinking, projecting, remembering and watching, Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show, set in the tiny town of Anarene, Texas, opens on their one movie theater, The Royal (Father of the Bride is on the marquee), panning to reveal a desolate Main Street with one traffic light, all dusty and fading and hanging on for dear life. Wind and leaves blow across the chilly landscape (shot so evocatively in black and white by veteran Robert Surtees) as we hear a car motor chugging. That’s Sonny (Timothy Bottoms) who struggles to get the heap going, freezing his ass off and fixing his radio dial to better receive Hank Williams’ “Why Don’t You Love Me?” Hank Williams will follow these characters all over the movie, commenting on and filling in the quiet they’re intent to avoid. He also matches many of the character’s spirits and Sonny’s especially – “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry.” The novel’s first two sentences begin: “Sometimes Sonny felt like he was the only human creature in the town. It was a bad feeling, and it usually came on him in the mornings early, when the streets were completely empty.”

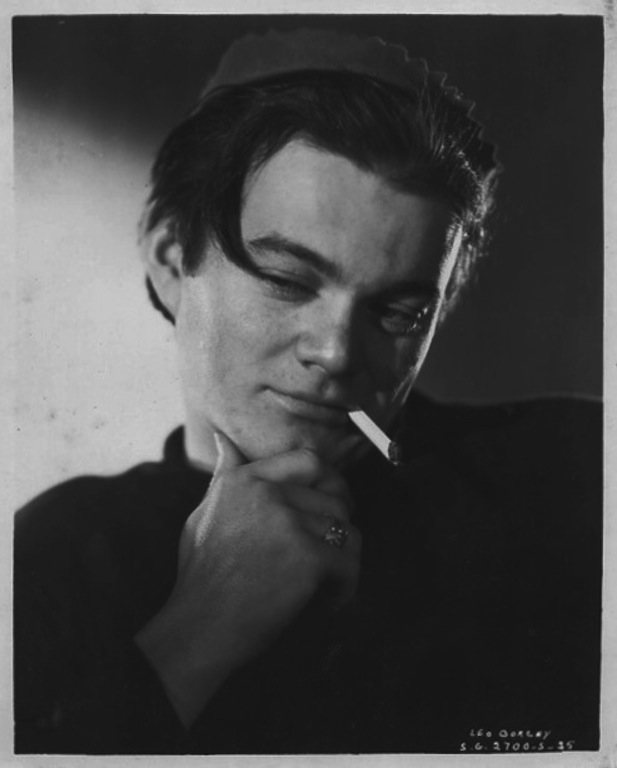

Sonny spies Billy (Sam Bottoms, the actor’s younger brother) sweeping the street and gives him a lift, playfully turning the younger kid’s baseball cap backwards, an affectionate refrain throughout the movie and they drive on to the pool hall. Through the detailed, formal but never stodgy, and incredibly lived-in excellence of Bogdanovich’s direction (and production designer Polly Platt) we are immediately transported right into this world that, at the time, was 20 year ago, but we don’t feel simple nostalgia about it (though we wished these places still existed. I do anyway). As beautifully shot and as intriguing as this town is, it also appears hard and unforgiving. Maybe life was simpler? Maybe? But as the picture goes on to show, it certainly wasn’t more innocent (that’s fine, nothing is) or easier (that’s also true). Watching it in 2017, Anarene is such a relic that it’s almost exotic. If these towns were dying then they’re sure as hell not surviving now unless you’re lucky enough to stumble across one on a cross-country road trip. But meeting Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson), a father figure to Sonny and Billy and, as we’ll soon learn, Sonny’s best friend Duane (Jeff Bridges), we feel warmer with his friendship (the place seems too small to say community). Even razzing the boys for their lousy football team, Sam’s a complex, even poetic man (though he’d never describe himself as such).

He’s the heart and soul of the town – and not in any corny way – and we grow so fond of him that it will bring on an almost sick despair to even think of him gone. If he ever leaves, the town will sag down further, almost on top of itself. Not only does Sam own the pool hall (where handsome-hard mystery man, Abilene, played by Clu Gulager, has his own key), but the diner and the movie theater. Sam provides all of the services for escape and joy it seems, but also wisdom and ageless camaraderie, even if he’s decades older than the boys. But he’s missing a piece in his life, and there’s something quite melancholy about him, specifically because he’s so gracious and lovingly worn-in. In a later, powerful moment, he recalls a memory to Sonny that, as spoken by Johnson, is so vivid and cinematic that we can envision the scene almost right there in front of us – his mind rolling a movie reel of the past as we watch him speak:

“You wouldn’t believe how this country’s changed. First time I seen it, there wasn’t a mesquite tree on it, or a prickly pear neither. I used to own this land, you know. First time I watered a horse at this tank was – more than forty years ago. I reckon the reason why I always drag you out here is probably I’m just as sentimental as the next fella when it comes to old times. Old times. I brought a young lady swimmin’ out here once, more than 20 years ago. Was after my wife had lost her mind and my boys was dead. Me and this young lady was pretty wild, I guess. In pretty deep. We used to come out here on horseback and go swimmin’ without no bathing suits. One day, she wanted to swim the horses across this tank. Kind of a crazy thing to do, but we done it anyway. She bet me a silver dollar she could beat me across. She did. This old horse I was ridin’ didn’t want to take the water. But she was always lookin’ for somethin’ to do like that. Somethin’ wild. I’ll bet she’s still got that silver dollar.”

“You wouldn’t believe how this country’s changed. First time I seen it, there wasn’t a mesquite tree on it, or a prickly pear neither. I used to own this land, you know. First time I watered a horse at this tank was – more than forty years ago. I reckon the reason why I always drag you out here is probably I’m just as sentimental as the next fella when it comes to old times. Old times. I brought a young lady swimmin’ out here once, more than 20 years ago. Was after my wife had lost her mind and my boys was dead. Me and this young lady was pretty wild, I guess. In pretty deep. We used to come out here on horseback and go swimmin’ without no bathing suits. One day, she wanted to swim the horses across this tank. Kind of a crazy thing to do, but we done it anyway. She bet me a silver dollar she could beat me across. She did. This old horse I was ridin’ didn’t want to take the water. But she was always lookin’ for somethin’ to do like that. Somethin’ wild. I’ll bet she’s still got that silver dollar.”

That woman turns out to be his greatest love and, he, the greatest love of the woman (who still lives in the town, Ellen Burstyn’s saucy and soulful Lois Farrow), deepening a character whom we might initially view as simply calculated and alcoholic. Not Lois. She’s hard but sexy as hell here (her opening shot reminded me of Lee Remick in Anatomy of a Murder), but when the ice in her drink cools, Lois seems like one of the wisest women in town. Refreshingly, Bogdanovich and Burstyn (and McMurtry) allow her to be a bitch, but a human-being bitch, and when she opens up and warms us with a smile or simply amuses us with a line, we genuinely like her. Few are simple or shallow in this movie, in fact, not even Lois’s daughter, Jacy (Cybill Shepherd), the prettiest, richest girl in town and girlfriend of Duane. Jacy’s been described by some writers as a cock-tease or even a femme fatale, but she’s a bit more complicated than that (as she is definitely in the novel). She’s a tease but she’s doing it for reasons that may appear cold-blooded, reasons more resourceful, yet confused and, yes again, cinematic. She wants a big story; she wants drama, romance; she wants everyone talking about her. Why not? There’s not much else going on and if she’s the prettiest girl, why sit around waiting for intrigue? So start it. She’s vain (she’s so lovely it’s hard for her not to be) but she’s also unsure of herself, adventurous and curiously sexual, though sometimes scared, without the movie showing her any condescension (her later moment with Abilene boldly proves this). When she finally tries to sleep with lovesick, horny Duane and, baffling to him, he can’t perform, she makes sure those outside the motel room watching in their cars think they just did it. She has an audience and she is going to be the star, virgin or no virgin, dammit. When her girlfriends excitedly bounce into the de-flowering chamber asking her how it was, she gives them her best movie star face, looking up, liquid eyes all dreamily: “I just can’t describe it in words.” Jacy really should get out of Anarene and move to Hollywood.

Sonny’s lover is not so Hollywood – the aforementioned Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman) – wife of the one the most unlikable characters in the movie – the coach. She’s pretty, frail, nervous, middle-aged, prone to crying or occasional anger, apologizing to Sonny, mad at him, then mad at herself. You feel for her, you want her to find happiness, but you’re not sure what to make of their union; if it should last at all. Sonny is still growing up even after growing up so fast. You grow up quickly in a town like this – working, running a pool hall, smoking, whoring, maturing past sexual interludes with bovine (mentioned in passing in the movie, in much more detail in the novel) – but he’s not weathered the 40 years Ruth has yet. And, yet, she seems like she’s done absolutely nothing in her life save for changing her bedroom wallpaper and serving cookies to kids. She hates her husband, she gets sick, she falls for Sonny. A lot more pain is in store for her and the Picture Show of Sonny – that lovely romance that makes her swoon and escape her depressing little house – could not be sustainable. But what’s wonderful about this movie is, hell. It very well could be, for good reasons or bad reasons or reasons somewhere in between. Sonny, nearly an orphan, loves (maybe, we’re not sure) and desires Ruth, but he also makes her feel childlike, and gives her an underage kind of paternal care. She’s less a mother figure (his mother is deceased), and more like the sweet, drug-addicted father he can’t count on. In the novel McMurtry writes of Sonny looking at Ruth: “There was something wild in her face that made Sonny think of his father – when she smiled at him there was a pressure behind the smile, as if something inside were trying to break through her skin.”

But Sonny is just so young, and in a final scene, as Ruth gazes at his innocent-looking eyes, his youth so strong, it’s both strangely upsetting and tenderly poignant. Bogdanovich lingers on this long enough for the viewer to truly feel that age gap. And Bottoms plays all of this with a quiet charm and longing, a longing for something (what is it?). His longing is so powerful that, in some cases, it’s simply his eyes, those cinematic eyes, looking as we look with him – surveying the land, the town, a face or even a tumbleweed – that gives us an overwhelming surge of beautiful heartache. Sonny’s already experienced two other beloved people die: one young (which he sees), the other old (offscreen, which feels so jarring since Sonny views everything) and both unexpectedly, that you wonder how much he’s truly processed in his mind. What is he thinking? He seems like the type who might get out of the town (and he tries, briefly) but, nope. Looks like he’s gonna stay. Will he always? Bogdanovich and McMurtry will not answer that. Not in this picture (you’ll need to read and watch Texasville to find out).

And now the movie theater has closed down (Sonny and Duane watch Howard Hawks’s Red River the final night before Duane heads out for Korea, another loss). No more time staring at the screen (TV is taking over) but Sonny will likely listen to more music and drink in whatever is in front of him or comes his way – the pool hall, the residents, newcomers, cars, random excitements, girls. Maybe he’ll go crazy. Whatever he’s doing or wherever he’s going, the fading town is still standing while he matures into another year. Sonny will continue to make his own movie memories through living, however that goes. One day he’ll likely weave a vivid impression of a time to one younger than him, just as Sam the Lion did. Maybe he’ll fall for another woman, hard. Wonder if it’ll be different? “Like in a movie.”