Talking Christmas With Shane Black

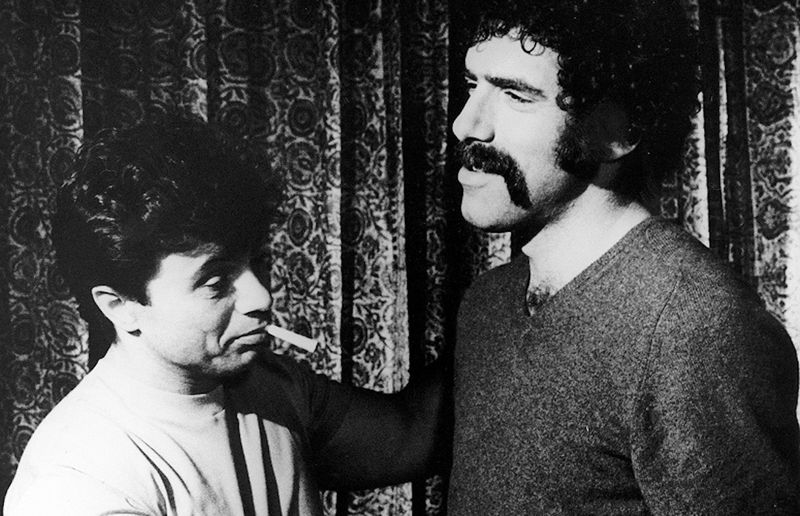

Shane Black makes a good cup of coffee. It’s December 21st, 2015, the holiday season, a perfect time to meet Shane Black. I’m watching Black work his coffee maker in his kitchen. He finds me cream. I find it disarmingly sweet, charming that we’re in his enormous, beautiful 1920's-era mansion, and he’s making me coffee. He’s wearing socks, no shoes. His two handsome dogs are running all over the kitchen. They jump on me, and he nicely tells them to stop. He loves his dogs and we watch one dive into the pool. Later we’ll walk around his house, check out a secret room with a delicious past and look at his libraries which includes lots of great vintage pulps with fantastic covers and countless original issues of “Doc Savage” and “The Shadow” as well as modern and classic mysteries and thrillers (some he calls “shitty” but likes reading them anyway, which is refreshing) and more and more. We talk for a long time about numerous topics and he's candid and unexpected. Endlessly fascinating, the boyish, but wise Black is honest, opinionated, pensive, incredibly intelligent, funny and self-effacing in a unique way. He’s unlike anyone I’ve ever met.

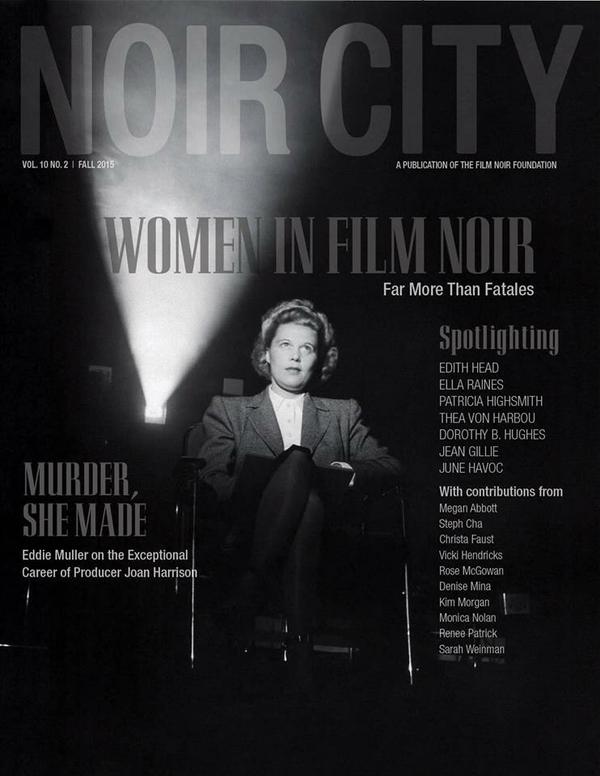

My interview with Black is for a much larger piece I will publish later. But, for now, I’m only sharing an excerpt, one that befits the holiday. Because there’s a consistent, the singular and often brilliant screenwriter and director (Lethal Weapon, The Last Boy Scout, The Long Kiss Goodnight, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang, Iron Man Three, the Amazon pilot Edge, and the upcoming and The Nice Guys, as well as the recently announced Doc Savage and Predator), is famous for: setting his movies during Christmas. I've written about Black's Christmas before and asked, within the piece, for him to further illuminate his Christmas fixation. When I finally met him during this holiday season, he did. And he did so beautifully.

Kim Morgan: I am going to ask you a question that everyone asks you because all of your movies take place during Christmas. What happened? Are you obsessed with Christmas?

Shane Black: I’m not obsessed with Christmas, I’m only obsessed with Christmas in movies. It grounds me, it makes me comfortable and happy to escape wherever I am into a movie that’s set at Christmas because you recognize that the hush that comes and the sort of rarified arena that it provides at that time of year [is good] for drama to take place. And also I think, the isolation people feel at Christmas is important (and also being in a blizzard is wonderful). The homecoming feel of people striving to come back to something at Christmas is important and also, just in Los Angeles, the way you have to dig for it. How, just tiny bits of Christmas exist here but they are things you have to unearth. Like, I remember walking at Christmas and seeing a little Mexican lunch truck with a broken Madonna and a candle in it. And I thought, that is as much, that is as powerful, as talismanic a bit of Christmas as the 40-foot tree at the White House. It’s like little guiding beacons to something we all recognize as a time to put things aside and focus momentarily on the retrospective of our lives; a spiritual kind of reckoning where we’ve been and where we’re all going to. All these things, I just love it in movies.

KM: And again, it can also be so incredibly lonely…

SB: Don’t make me cry [Laughs] Look around. I’ve got two dogs and a big house.

KM: Christmas in Los Angeles is very strange. When it’s absurdly hot, the decorations on Hollywood Blvd. are just sagging there, all depressed and dejected looking. It seems cliché, but it’s like all those with sagging hope and dreams, trudging around the city, trying to keep it cheery. It can be so depressing and touching. And so dark, in the light.

SB: If you like noir — the idea of little glowy bits, striving for some kind of attention in the middle of a non-snowy downtown L.A. landscape, the iconic nature of Christmas, that’s sort of blotted-out or hidden, but that still informs everything around it. Noir is about awakening from paranoia, hatred and depression to latch onto the one true thing that you have and inkling of. And that inkling sustains your faith throughout. And by the end, hopefully by the end: “I believe that one thing; everything else is falling apart, I’m shot and I’m dying but it’s for a reason because I believe one thing.” And so, to embody that as Christmas in L.A. I don’t know that it means any specific thing to believe in but it just means something.

KM: And that trying to believe, and during Christmas in Los Angeles… I mean, there’s that Scientology Santa siting there, adding to the surrealism and even darkness. That feels noir and almost Lynchian. You can feel so lost…

SB: Yes.

KM: But, then, in my neighborhood Koreatown, I’ll hear Mexican families singing and holding candles. It’s so haunting and lovely and far more beautiful than pristine decorations in Beverly Hills.

SB: Well, to me, when I was a kid it’s something that had a heavy impact, I was walking downtown Pittsburgh on a street, and it was late at night, the wind was blowing, and it was very dark, and all of a sudden down the street, for some reason the streetlight went out and there was just a woman, a fat woman, who was just sort of standing in the window looking out and there was just this one little thing of light, it was chiaroscuro, everything else was dark, and the idea of beacons, and the candles in the woods. I talk about the Robert Frost poem, being lost in a dark wood, and the idea of the secret light in the window, also seeing a light in a window and knowing that there’s a destination that’s vaguely seen or even sensed but not quite seen, and just so far off the path you can go to, and the lights that could steer you back onto the path; it’s vague and if you put those images in a movie one in a thousand people will say “Yeah, it was about being taken off the path and finding your beacon.” But, there is that element of me that’s just… the magic underneath Christmas we are briefly, almost fleetingly, aware of a magic that could be there. If we just stopped long enough to pay attention. And the perfect expression of this, more than anything else I could ever tell you is, "The Cricket in Time’s Square." Christmas in Time’s Square with that little cricket, that’s what we’re talking about. That’s noir.

Merry Christmas. Now go watch some Shane Black. Or read The Cricket in Time's Square. And stay tuned for my longer interview with Black.