“The Hired Hand is the America of what Walt Whitman means to me. I’d respect Peter for no other reason than showing me the family as an ideal unit. That’s very close to me, I’ve gone through divorce.” – Warren Oates (“Warren Oates: A Wild Life,” Susan Compo)

“Morality sucks. Clearly, so does gravity, but we can prove gravity. We can’t prove morality. It doesn’t exist at all. Don’t pay any attention to it. Those were the characters that Alan Sharp had written so beautifully. He has this old slang of that time. It comes just rolling off Warren Oates’ tongue, and you’re right there in that time in 1881. It wasn’t really a three-way deal, sexually, but the inference was that she was not a bad person, but that she didn’t have any compunction about forgetting the man who ran out on her six years earlier, and having sex with someone else. Women get horny, too. They did in 1881.” – Peter Fonda (Onion AV Club interview, 2003)

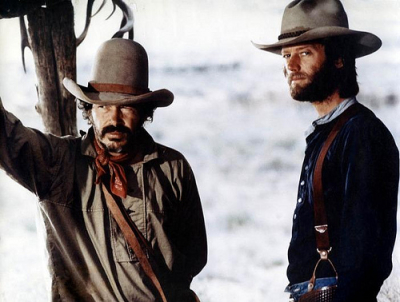

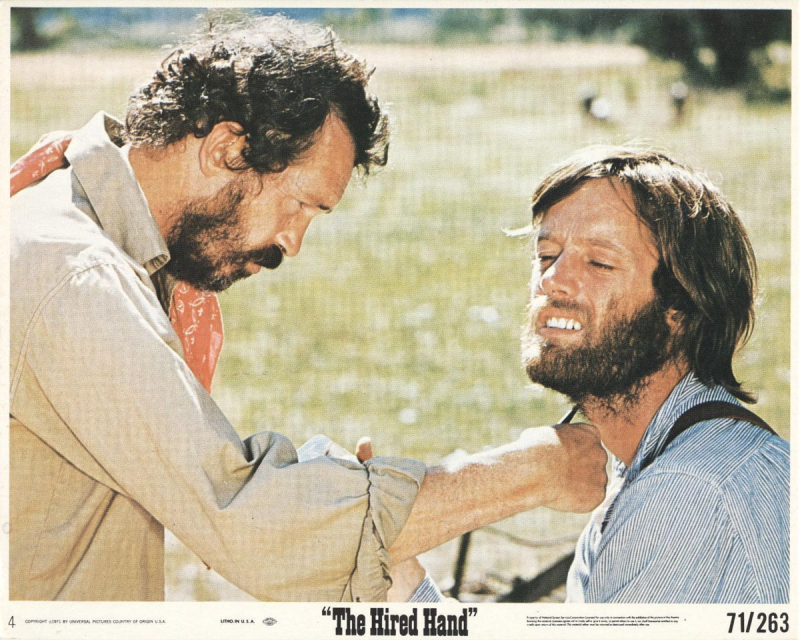

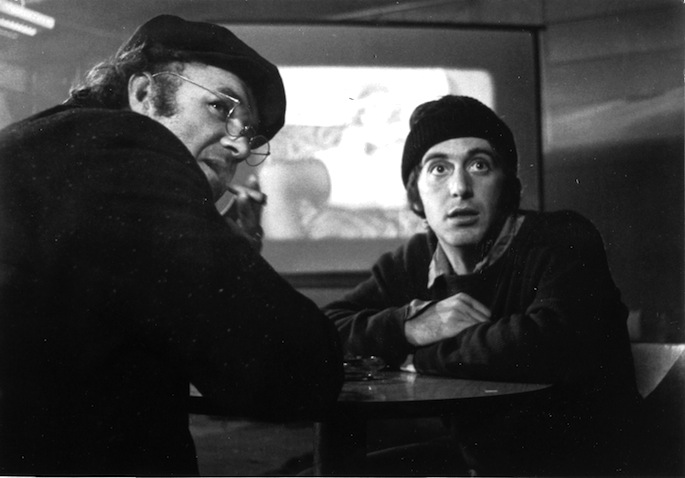

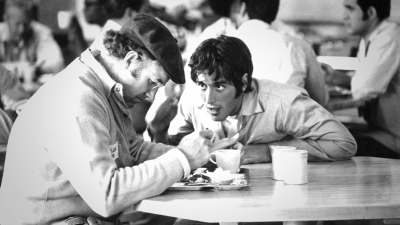

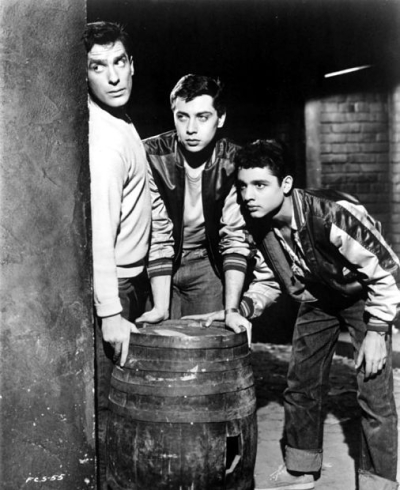

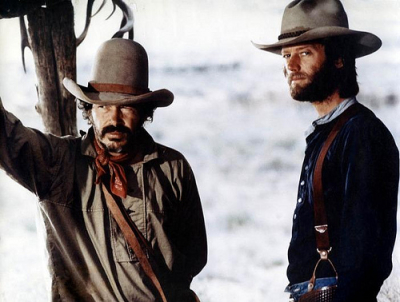

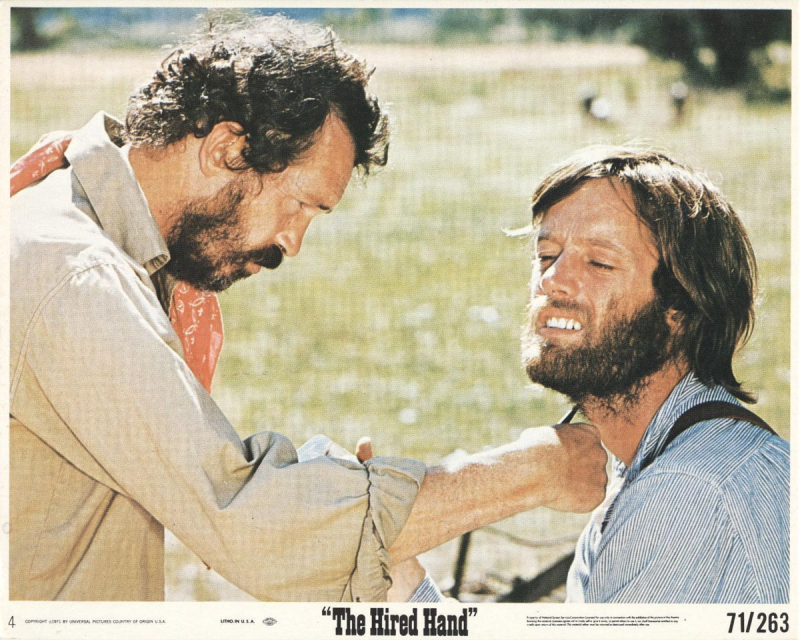

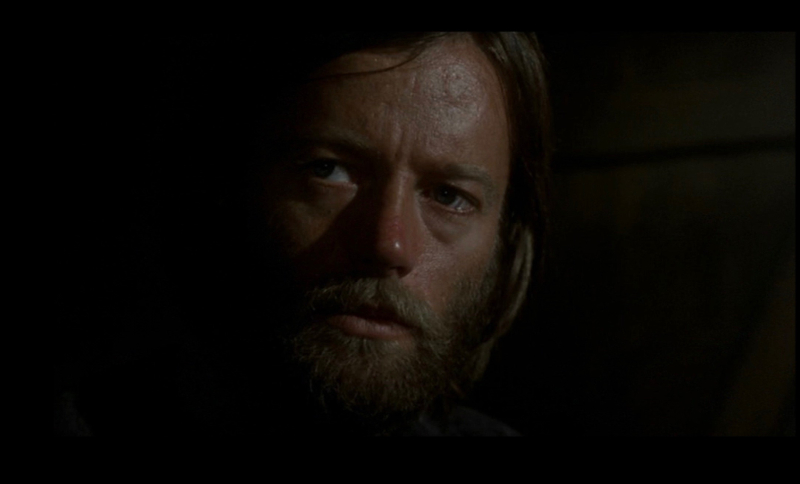

Peter Fonda and Warren Oates looking at each other – it’s an achingly beautiful thing. You feel the depth and concern of these two men, their friendship, lived-in and real, their faces, one blonde and stoic, sometimes dreamy-eyed and languid, a little lost, mysterious; the other dark-haired and soulful, but wily, and with a toothy grin and crinkly smile that can veer from loving laughter to murder ballad darkness – as Oates put it himself, a face like, “two miles of country road.” Captain America and Bennie. Iconic oddballs. Gorgeous in their own way and so deeply American. You see them together, take in their natural chemistry, and think, of course they love each otherTake this scene in Fonda’s elegiac, western, his masterpiece, The Hired Hand – it’s the moment in which we learn Fonda’s cowboy drifter, Harry Collings has a wife he left seven years ago. One of their riding companions, the youngster of the three, Dan Griffen (Robert Pratt), seems little interested, he doesn’t understand the depth or importance of this revelation and prattles on while Harry’s best friend, Arch Harris (Oates) looks at his good friend. Fonda gets up from the saloon and walks towards the door, as he walks, face melancholic, Oates watches him as if no one else is in the room. Dan says to Arch, “The hell with him we can go to the coast together…” and Oates states, while still watching Fonda, the seven years. Seven years – it’s been seven years that the wife and kid have been waiting for Fonda, or lamenting he’s never coming back, or perhaps forgetting he ever existed or not even caring if he does anymore. Who knows how they feel? His eyes are full of compassion and concern and maybe even worry as he gazes at his friend, studying his movements, knowing right then and there, without saying anything, this is a significant event.

Peter Fonda and Warren Oates looking at each other – it’s an achingly beautiful thing. You feel the depth and concern of these two men, their friendship, lived-in and real, their faces, one blonde and stoic, sometimes dreamy-eyed and languid, a little lost, mysterious; the other dark-haired and soulful, but wily, and with a toothy grin and crinkly smile that can veer from loving laughter to murder ballad darkness – as Oates put it himself, a face like, “two miles of country road.” Captain America and Bennie. Iconic oddballs. Gorgeous in their own way and so deeply American. You see them together, take in their natural chemistry, and think, of course they love each otherTake this scene in Fonda’s elegiac, western, his masterpiece, The Hired Hand – it’s the moment in which we learn Fonda’s cowboy drifter, Harry Collings has a wife he left seven years ago. One of their riding companions, the youngster of the three, Dan Griffen (Robert Pratt), seems little interested, he doesn’t understand the depth or importance of this revelation and prattles on while Harry’s best friend, Arch Harris (Oates) looks at his good friend. Fonda gets up from the saloon and walks towards the door, as he walks, face melancholic, Oates watches him as if no one else is in the room. Dan says to Arch, “The hell with him we can go to the coast together…” and Oates states, while still watching Fonda, the seven years. Seven years – it’s been seven years that the wife and kid have been waiting for Fonda, or lamenting he’s never coming back, or perhaps forgetting he ever existed or not even caring if he does anymore. Who knows how they feel? His eyes are full of compassion and concern and maybe even worry as he gazes at his friend, studying his movements, knowing right then and there, without saying anything, this is a significant event.

Fonda’s face says, without words, I have a wife and kid out there. I need to go back. Oates’ face says: He has a wife and kid out there. He should go back. And then there’s the added question mark to Oates’ gaze: But will I lose my friend if he does? It’s a meaningful exchange of such subtle, empathetic acting and beautiful, pure chemistry — they are so … powerful together. You believe every moment between them. It’s a meaningful exchange of such subtle, empathetic acting and beautiful, pure chemistry – they are so … powerful together. You believe every moment between them.

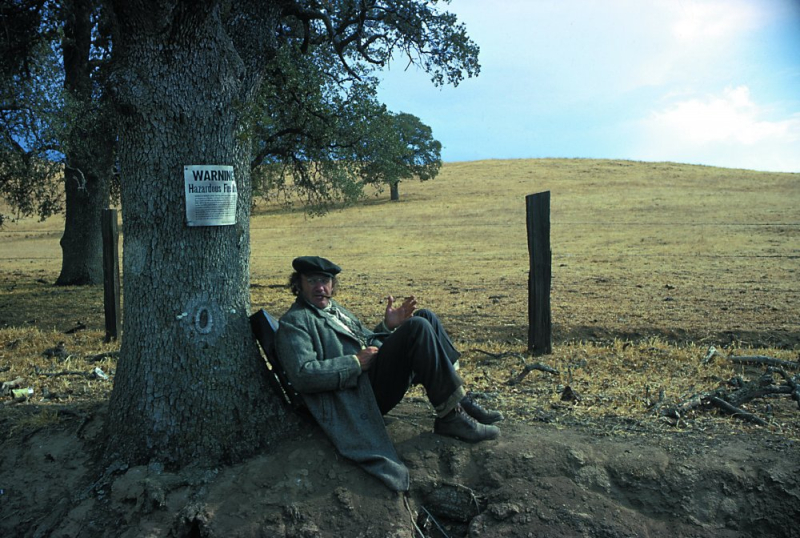

The Hired Hand was a first for quite a few people, a movie made with love and vision and the care to be quiet and reflective, something that came off both hippie dippy to some, and simple and sincere to others. Or both. Or perhaps it’s really a unique alchemy of many things. A revisionist western, or a hippie western, or just a different kind of western, the way Monte Hellman’s masterful The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind are so spare and existential, showing the west as a place full of mystery – mythic, yes, but the mythic almost looming over characters as a reminder of what once was, or who they should be, but also confusing; a place full of rough absurdities. Fonda’s reflection (from a lovely script by Scottish novelist and screenwriter Alan Sharp who wrote Ulzana’s Raid and Night Moves) was spare, if that is even the right word considering how visually stunning and scored the picture is. It also played with mythic ideas – what one should be or is required to be or was thought to be back then as a roaming man – but it was also bound to family and friendship and the struggle to come to terms with … a woman.

Not just duty to a woman in a traditional sense, but a woman’s needs. It asks, what happened when he left? This is and was a refreshing question and Peter’s sister, Jane was pleased that it was what one would call something you don’t hear much of – a “feminist” western. His father, Henry, a western hero, reportedly admired it as well. Surely this made Peter happy, particularly with family at the core of this movie. In fact, at one point Fonda wanted his father to play the Warren Oates part. Fonda Sr. thought he was too old. Well, that would have been interesting, but Oates is so beautiful here and the movie is so powerful, so singular, that it works in every way. Every way. Alas, when released, Universal didn’t think so, which is really, really unfortunate. Though the film received mixed reviews, some quite impressed, the studio was upset with the final product. This was not the western they wanted, and it played in theaters for a scant time. It was pulled and buried in obscurity. You watch the movie now and that makes you angry. It wasn’t until 2001 that Fonda re-released it in a lovingly restored director’s cut (he also made the film shorter), and finally received the adulation and attention it deserved.

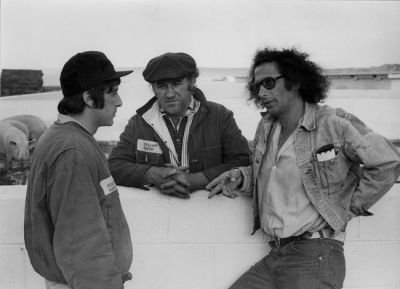

It was also a movie in which Fonda was given full artistic control. Coming off the phenomena and financial success of Easy Rider (1969), Universal allowed Fonda TheHired Hand to be his movie, his debut. Since Fonda co-wrote, produced and starred in Easy Rider, trust was granted, or perhaps a “this is what the kids want” devil may care attitude. How could it fail? After the counterculture, and everyone, embraced Easy Rider– yes. This is Captain America’s movie – people will go. Not surprisingly, that same year, Universal allowed Easy Rider co-star, and director, Dennis Hopper, to take off and make the fascinating, experimental The Last Movie, a notoriously complicated experience, and something that wasn’t a commercial success (it won the Critics Prize at the Venice Film Festival, but didn’t fare well financially and was mixed, critically, in the states, the New York Times called it “an extravagant mess,” though Stanley Kaufman championed it). Both men were and are talented directors with their own unique style and vision. The reaction to The Hired Hand reportedly left Fonda with a kind of gentle disappointment. That’s upsetting – it should have hung around longer, it should have been seen on the big screen (in initial release) more. It needs to be seen on the big screen. The fact that this film became more available in the 2000’s (on DVD), and was re-released in a director’s cut, underscores all those years Fonda was saddened by its quick obscurity. From 1971 all the way to 2001. That’s a long time. As Fonda say, “Universal tried to bury this film back in ’71. But the people who loved it really loved it. And they’ve kept on loving it.” They do (including Martin Scorsese) and they continue to.

Fonda directed this sweet, painful, gritty, gorgeous, mystical and emotional story with a visual lyricism that tells its tale through its images (and score) as much as the script does. Working with the relative newcomer (in America), cinematographer Vilmos Zsigmond. The Hired Hand has been deemed his first movie, but he shot, distinctly, James Landis’ The Sadist and the underseen James Bruner picture, Summer Children, before that, and some other B movies – you can see the master’s talent and style in those movies. (Zsigmond said, “Before that, I basically did commercials. The Hired Hand was probably the first time that I actually had a dramatic story with good actors.”) But the magnificent, highly stylized choices he and Fonda worked with here immediately set the picture apart and certainly cemented Zsigmond’s tremendous craft – it’s a uniquely stunning picture. The long lenses, dissolves, slow motion, the figures in silhouette, the lens flare and the exquisite, expressive colors –all of this – created a superb tone poem of imagery that, at times, feels transcendent. (Editor Frank Mazzola’s lyrical montages also swirl into the mix, underscoring or adding emotions and mystery.)

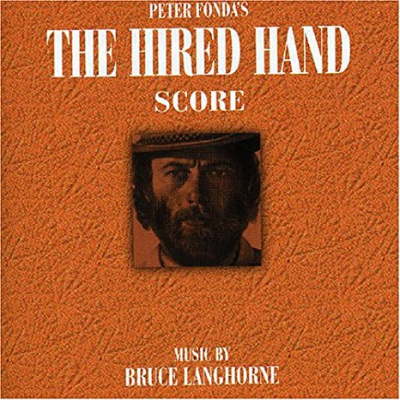

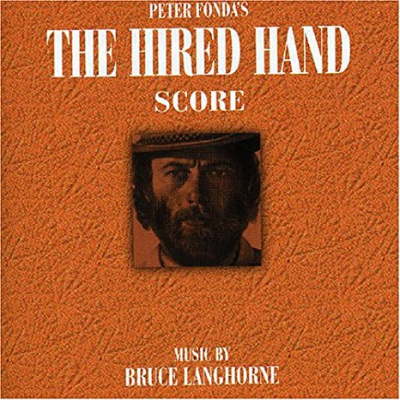

An early scene of Fonda riding his horse through the water shows him in an almost other-universe of light, color and nature – he’s suffused in a deeply blue world, and he no longer looks like just a man on a horse, but he looks like a man in a painting. Adding to this poetry is the brilliant score by Fonda’s friend, Bruce Langhorne, who had never scored a movie. A musician, and session man, who had worked in Greenwich Village with everyone from Bob Dylan (Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” was inspired by Langhorne, he also played on many of Dylan’s records) to Joan Baez to Richie Havens, Langhorne’s score is a character in itself, speaking when the film needn’t, but never obtrusive. Using varied instruments including soprano recorder, harmonica, upright piano, organ, dulcimer, and fiddle, the effect feels the landscapes Fonda directs, it instinctively understands the emotions conveyed on screen, while weaving itself into the poem of a movie. The score became as famous as the movie, and was released 35 years later. As Scissor Tail editions described:

“[Langhorne] opted out of scoring the film in a projection room, instead chose to shoot the film onto a small black and white camera to take back to his home in Laurel Canyon. He would watch the film and play along to it as his girlfriend at the time would record him and play it back, allowing him to overdub Farfisa Organ, piano, banjo, fiddle, harmonica, recorder, and Appalachian dulcimer onto his Revox reel to reel. Bruce’s 1920 Martin guitar is most prominent throughout the record. The Results were a uniquely wide and lonesome soundscape. The closest comparison might be Sandy Bull or possibly John Fahey, but nothing of its kind or even of its time poses a resemblance to Langhorne’s minimal masterpiece."

“[Langhorne] opted out of scoring the film in a projection room, instead chose to shoot the film onto a small black and white camera to take back to his home in Laurel Canyon. He would watch the film and play along to it as his girlfriend at the time would record him and play it back, allowing him to overdub Farfisa Organ, piano, banjo, fiddle, harmonica, recorder, and Appalachian dulcimer onto his Revox reel to reel. Bruce’s 1920 Martin guitar is most prominent throughout the record. The Results were a uniquely wide and lonesome soundscape. The closest comparison might be Sandy Bull or possibly John Fahey, but nothing of its kind or even of its time poses a resemblance to Langhorne’s minimal masterpiece."

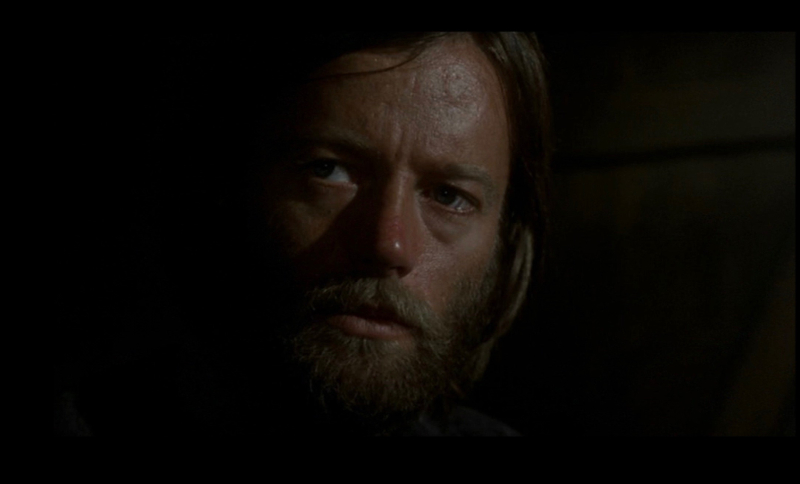

There’s a dreaminess to The Hired Hand that shifts between feeling live and direct, and then, wistful, faraway, like you are always reaching for something, and even if it’s right in front of you, speaking frankly, you’re looking beyond. Or trying to understand something larger than yourself. You see it in Fonda’s eyes, you see it in Oates’ eyes, and then you see it in moments that you’re not even sure of – like when coming across something very real that doesn’t look real, not at first. Not right away.

What comes across is when the men (including young Pratt) find a dead girl in the water – something that feels not just incredibly sad, but portentous to the understandably disturbed men. A dreamy, natural reverie is interrupted by something that’s at first unreal, and then shapes into what is tough and hard in life, and something of which they know of – of course. But this girl’s death feels like something else. And it makes them think. It makes you think as well. People die. And women die. With those thoughts lingering, Fonda begins pondering life, that wife he left behind. Fonda needs to go back. That little girl in the water – dead as anything and drifting – that could be her. Or him. Or anyone. Life needs to change. Or at least it needs to stop drifting the way it is.

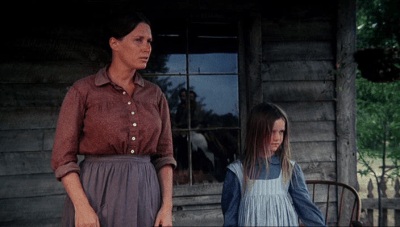

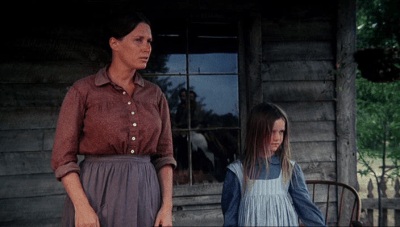

This is when Verna Bloom comes in. Or, rather, Fonda returns to her, his wife. An excellent stage-trained actress (she had made two movies prior, Medium Cool and Street Scene), Bloom is wonderfully unadorned here, though uniquely lovely, and she’s playing older than her co-lead by ten years (the actors were, in fact, the same age). I love her performance – she’s at once, matter of fact and sexual, then hard, then vulnerable. She’s complex. She’s real. She’s so real, in fact, that her sexuality feels striking and so refreshing that it’s almost startling to see, and not in any obvious come-hither way, but in the way that women just need to be pleased, like any man needs to be pleased. And she’s so open about it.

When Fonda does come back (almost like a new relationship) and back to their child, who has now grown into a young girl of about ten (again, you think of that portent at the film’s beginning), he brings his best friend Oates with him. The wife is skeptical at first. This man abandoned her. Why should she allow him back in her life? And who is this other guy? How is this going to even work? Fonda doesn’t ask to be her husband again, not right away, but just to work as her hired hand. He’ll work for his wife, he’ll get to know her again, if she likes. In a potent little moment, she asks, “Why’d you come back?” He answers, “Got tired of the life.” It’s a spare exchange, and she is maintaining her strength, her toughness, but Bloom is so marvelous, you can feel her emotions vibrating under that hard shell.

This is where the film turns into something audiences probably weren’t expecting: a movie about a man who returns to his wife and a movie about a man who comes to terms with her sexuality. There’s a frank exchange between the two of them after Fonda and Oates have heard in town about how many men she’s slept with since he left – all the hired hands she takes to her bed – the typical “the woman is a whore” moment. The two men are livid, and further than that, Fonda is confused. But later that night, he discusses the situation and talks with her and … she lays it out, bare. Essentially, she says: You left, I walked this house lonely night after night, and then, I decided to do something about it. She did do something about it. She states: “Sometimes I’d have him and he’d have me… But not all of them…” It addresses many of those westerns in which you wonder, what are the women thinking about, past their husband, past their children, past the horses or whatever else? All those things lingering in movies – like the sexual tension between Alan Ladd and Jean Arthur in Shane, or the obvious unspoken past love between John Wayne and Dorothy Jordan in The Searchers. Those women weren’t alone like Bloom is in this picture, but clearly, they wanted other men too, even while married. And the men who wandered off drifting, just as Fonda did in The Hired Hand, well, they wanted to sleep with them, and they wanted their love. You know Ladd’s Shane is yearning for something, something to hold on to. Here, had Bloom so desired, she would have invited Shane in and held him close. And more. As Fonda said in an interview, “Women get horny too. They did in 1881.”

But what ties all of this tension and yearning and attempts at understanding together so gorgeously and perceptively is Warren Oates, the best friend. He is so close to Fonda that Bloom accuses him of marrying him, not her. (Oates and Fonda would go on to become best friends themselves, Oates both pal and father figure, and they’d memorably make other pictures together, including Race With the Devil and 92 in the Shade). Fonda understood Oates as more than a character actor, he got his depth, his experience, his sex appeal: “I had watched Warren in a couple of films and realized there was something else going on in this man. When he wasn’t playing the assistant sidekick character or the doofus goofus role, he had this quality which in a strange way was dashing—like Bogart. He had to play wisdom and experience and when it came time to cast the role, I didn’t even think of anyone else.”

And you get his sex appeal in The Hired Hand right alongside Bloom. Bloom doesn’t resent Oates as an interloper, and, instead they, too, share lovely moments together. He treats her with the utmost respect, something that feels supremely touching, as women are so frequently not treated that way. At times you think, who are these men? Why are they so patient and accepting? But, then, you further think, why wouldn’t they be so sensitive? Drifters, misfits, however they would be labeled, who is to say the Old West wasn’t full of unconventional situations not ruled by fear of God or the townspeople’s gossip or typical “masculine” attitudes that we all think everyone exhibited back in the day? I mean, of course it wasn’t all that. And why should these men and this woman care what people think? They just want to start their lives over again and keep the family together – who cares about the petty gossips? As exhibited by that poor girl in the water – people die – adults die. People you love die. They know that.

Oates is with them in regards to these sentiments – live your life – though he realizes his own attraction could be getting in the way of his friend. He wishes for Fonda to just be with his wife and restore the original family. And, so, he leaves. It’s a gently heartbreaking moment because, well, we don’t want him to leave. It feels wrong and even a little scary. And, in the end, perhaps he shouldn’t have left – trouble awaits him. The trouble isn’t his fault, but this past trouble catching up with him, ropes in Fonda. And Fonda will … I can’t say anymore. Oates will return to Bloom, bringing Fonda’s horse with him. Whether or not he will stay is up to question, giving the movie its aching, high lonesome power… we want him to stay. Someone stay. Someone stay because nothing lasts. In an earlier scene between Oates and Bloom, she fears Fonda will leave again, and says resolutely and with fear, “He’ll go. Just a matter of time.” Oates answers with a line that sums up the film, the west, life, the nature of love and friendship, even his own mortality and loving union with Fonda, he says: “Well, most things are, ma’am. One way or the other.”

Originally published at the New Beverly, extended from my essay for Arrow.