“Little Murders was conceived as an essay on what I perceived to be going on in America in the mid-1960s…’inspired,’ if you will, by the assassination of JFK and the shooting of Oswald a week later. The post-assassination climate of urban violence made me realize this country was in the process of having an unstated and unacknowledged nervous breakdown. All forms of authority which had been previously honored and respected, on every level of society, were slowly losing their validity.” – Jules Feiffer

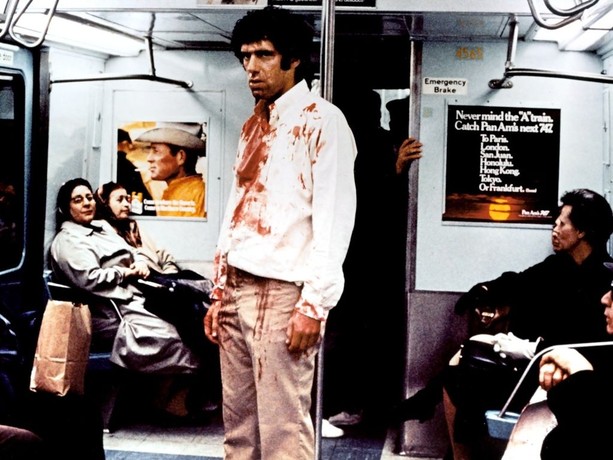

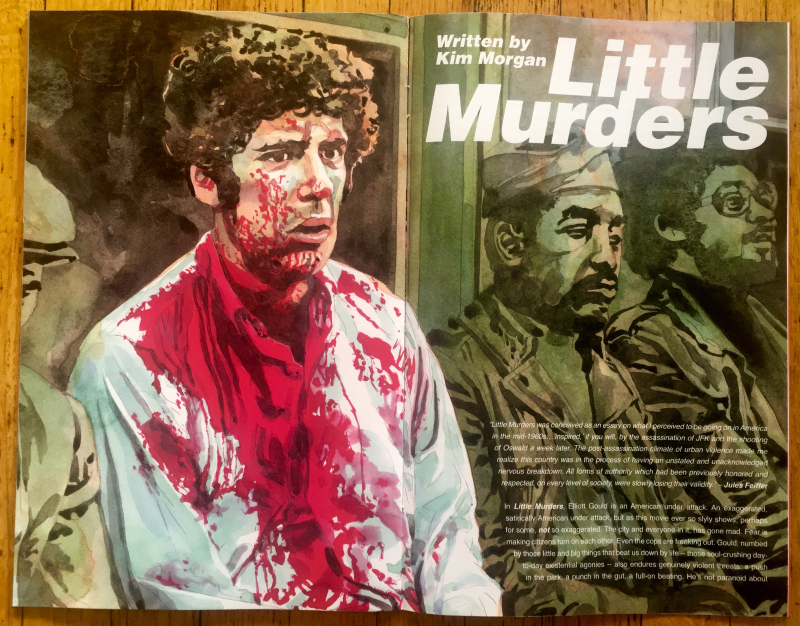

In Little Murders Elliott Gould is an American under attack. An exaggerated, satiric American under attack, but as this movie ever so slyly shows, perhaps for some, not so exaggerated. The city and everyone in it has gone mad and fear — so much fear — is making citizens turn on each other. Even the cops are freaking out. Gould, numbed by those little and big things that beat us down by life — those soul-crushing day-to-day existential agonies — also endures genuinely violent threats: a push in the park, a punch in the gut, a full-on beating. He’s not paranoid about those waiting in the alleys anymore because, why? Why be paranoid if you’re beat up nearly every day? Gould is so directly in touch with these perils that he’s adopted a nihilistic nonchalance of protection and simply shrugs off the offenses. He doesn’t find the need to fight back, not because he’s a pacifist, but because he’s an “apathist.” As he explains to his soon-to-be-wife’s parents in perfect Elliott Gould deadpan: “Well, there's a lot of little people who like to start fights with big people. They hit me… And they see I'm not gonna fall down. They get tired and they go away. It's hardly worth talking about.”

It’s both a strangely reasonable rationale (people will stop, you might wind up dead but they will eventually stop hitting you) and an absurdly funny display of dispassionate blunting: he says he hums through the pain and thinks of something else, like taking pictures (he’s a photographer). Makes sense — if the world feels insane — and it often does, especially now. Cartoonist, playwright and screenwriter Jules Feiffer wrote this in response to what he deemed America suffering from: an “unacknowledged nervous breakdown.” That was 1967. And here we are (as I wrote this — 2017) — now, it's 2025.

Little Murders is a satire, but never beyond reality – it’s so brilliantly observed, so smart, so hilarious, and so disturbing, that watching now, the picture moves beyond a time capsule of New York City circa late 60s early 70s and into the dark heart of American madness. And in the grand American literary tradition — Hawthorne, Melville, Poe — we are all a little crazy: Said Poe, “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

I’m not sure if anyone displays simple sanity (whatever that means) in Little Murders — maybe (OK, not really) Patsy Newquist (played by Marcia Rodd) who is trying her hardest to at least be optimistic in a city full of muggers, shootings and heavy-breather obscene phone calls that follow her from apartment, to parent’s place to even a payphone at her wedding. But trying is indeed a “horrible sanity” in this movie’s unsparing universe, so when she meets Alfred (Gould) as he’s getting attacked outside her flat, she does the most insane thing imaginable, she falls in love. Her version of love is to “mold” Alfred, a photographer who takes pictures of dog shit (a jab at the art world? Or he’s a really talented photographer of dog shit? I say both), and she urges him to listen to her schizoid entreaties: “I want to be married to a big, virile, vital, self assured-man that I can protect and take care of! You've got to let me mold you. Please! Let me mold you!” Gould’s not so sure about this whole love thing but he proclaims a more powerful declaration: “I trust you! I very nearly trust you!” For a guy like him, that’s saying a lot. Hell, that’s saying a lot of anyone.

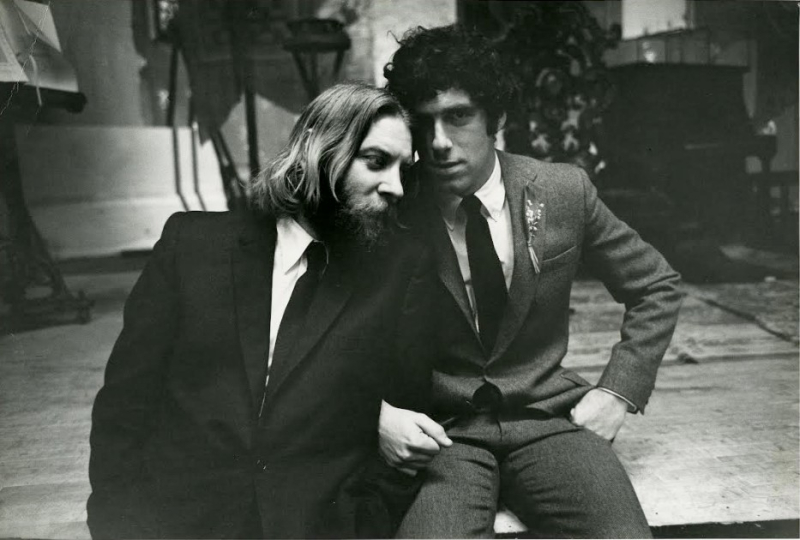

Directed by Alan Arkin and shot by Gordon Willis, this 1971 adaptation of Feiffer’s genius, pitch-black comedic play still feels like nothing you’ve ever seen before. The beats of the movie, from hilariously nutzo family dinners to genuinely reflective moments of horror (like a blood splattered Gould on the subway), remain potently uneasy. This is not a comfortable movie, nor should it be. For that reason, one can understand its fascinating backstory as a play. First running in 1967 and starring the great Gould, it only played seven nights and then closed. People weren’t ready for it, perhaps; something didn’t click, or something clicked too much. Two years later, after America had been batted around enough (and would even more in the ensuring years), it played off Broadway, this time to great success. As for the film? In 1971 so much had hardened in this country.

In Feiffer’s vision no one is spared. He’s not being conservative at all — this is not a decrying of city violence or a return to values. I believe Feiffer is instead a shrewd, frustrated observer, while giving what we hold “sacred” a raspberry. Patsy yells at Arthur to fight back, she can’t stand his apathy. She’s right, but then she’s not right. She ceaselessly questions his masculinity as Gould in all of his tall, dark, offbeat Belmondo prime, wanders around in a bemused daze — he's a guy who could likely land a punch but doesn’t want to. Maybe that’s just as masculine, not giving a fuck. Everything is questioned here. Patsy’s family, the conservative father (Vincent Gardenia) who thinks everyone’s a “swish” and is so fearful of appearing weak that he hollers at anyone who states his first name (“Carol”); her “come and get it!” mother (Elizabeth Wilson) who sits Arthur down to show him pictures of their dead son because she figures Arthur likes photography; her bizarre little brother (a hilarious Jon Korkes) who moves around in constant comic motion, lurching and smiling and making noises to be humorous (we think), and he is funny, albeit with a kind of sinister brotherly love (he and Patsy have some underlying incestuous dynamics).

Their apartment feels like a bunker as shots are fired outside and the “typical” American family is holed up, a group of loons, no crazier than Arthur and, yet, strangely recognizable if you’ve ever felt unsure meeting a partner’s family. Arthur’s intellectual parents are a different kind of nuts — they only speak through books — and so when he drops in on them (he clearly hasn’t seen them in forever) and questions his childhood — they can only answer through literary, philosophical and even cinematic reference. It’s funny, but it’s a bit heartbreaking as Arthur returns to Patsy, defeated, and, then defeated to become what she wants. He discusses his past college days when he was an activist and the FBI was on his tail. He says, "It was after this that I began to wonder…. why bother to fight back? It's very dangerous. It's dangerous to challenge a system unless you're completely at peace with the thought that you're not going to miss it when it collapses."

Feiffer, who also wrote Carnal Knowledge, released the same year as Little Murders (what a year) is relentlessly, hilariously toxic and yet, one never feels pushed away from the movie. The characters become weirdly likable; we start caring about them, we understand their anxiety while questioning those sacred institutions right along with Feiffer and Arthur: There’s a fantastic wedding scene with Donald Sutherland as a hippie reverend, announcing vows that are hysterically sensible:

“So what I implore you both, Patricia, and Alfred, to dwell on, while I ask you these questions required by the state of New York to ‘legally bind you’ — sinister phrase, that — is that not only are the legal questions I ask you, meaningless, but so too are the inner questions that you ask yourselves, meaningless. Failing one's partner does not matter. Sexual disappointment does not matter. Nothing can hurt, if you do not see it as being hurtful. Nothing can destroy, if you do not see it as destructive. It is all part of life, part of what we are.”

Another powerful, eerily prescient moment comes after Arkin’s paranoid cop flees the Newquist’s apartment, summoned when Patsy’s been killed (yes, this happens — she’s randomly shot). Mr. Newquist loses it and delivers a speech with crazed, paranoid satirical pronouncements that now, don’t seem so satirical anymore:

“What’s left? What’s there left? I’m a reasonable man. Just explain to me, what have I left to believe in? Oh, I swear to God, the tide is rising… We need honest cops! People just aren’t being protected anymore! We need a revival of honor and trust! We need the army! We need a giant fence around every block in the city—an electronically-charged fence! And anyone who wants to leave the block has to get a pass and a haircut and can’t talk with a filthy mouth. We need RESPECT for a man’s reputation! TV cameras, that’s what we need, TV cameras in every building, lobby, in every elevator, in every apartment, in every room. Public servants who ARE public servants! And if they catch you doing anything funny, to yourself or anyone, they BREAK the door down and beat the SHIT out of you! A RETURN to common sense! We have to have lobotomies for anyone who earns less than 10,000 a year. I don’t like it, but it’s an emergency. Our side needs weapons, too! Is it FAIR that THEIR side has all the weapons? We have to PROTECT ourselves and STEEL ourselves. It’s FREEDOM I’m talking about, goddamn it. FREEDOM!”

By the end, Arthur finally breaks down after snapping pictures of people in the park, and it’s important we see he’s shooting people, not shit, which may seem like a bright new beginning. Really, it’s an on-the-nose (but perfectly on-the-nose) symbol of what’s to come. He brings home a rifle and the family embraces violence. They smile and laugh and celebrate crazily, but there’s no catharsis. They sit down to dinner and it’s all so terribly sad. It’s also terribly funny. And terribly timely.

My piece was originally published in 2017 for Ed Brubaker's Kill or Be Killed

Little Murders is playing tonight, June 1, at 7 PM at Egyptian Theatre | Q&A with actor Elliott Gould. Moderated by Larry Karaszewski.