Felix E. Feist’s The Threat

“When I accepted the assignment to take over Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., Marvel Comics’ four-color 007 facsimile, the series was shambling through creative purgatory, charted by a knot of writers and artists who (with the exception of Jack Kirby) apparently didn’t know or didn’t care about its direction—or, more appropriately, its lack of direction… I might have used Charles Bronson, Kirk Douglas, James Coburn, or other cinematic tough-guys upon which to build my matrix, but instead opted for one of my favorite character actors: Charles McGraw. Whether playing heroes or villains, he was always as hard-boiled as they came, always just as ready to shut anyone up with a backhand slap as with a warning. His vocal delivery neatly summed up everything he brought to the screen: a predatory growl as harrowing as that of a cornered tiger’s, bristling with menace, and suggesting a penchant for violence beyond that of his blunt, granite features. Sometimes there was even a harsh, metallic quality in his timbre, like that of a Sonovox voice amplifier. Something beyond human. Perhaps something even less than human. The voice of Charles McGraw personified what I felt Fury was all about. His was the voice I heard as I wrote him into the S.H.I.E.L.D. saga. His voice was the core of the character, the point at which every adventure began and ended..” – Jim Steranko, from his intro to Alan K. Rode’s “Charles McGraw: Biography of a Film Noir Tough Guy”

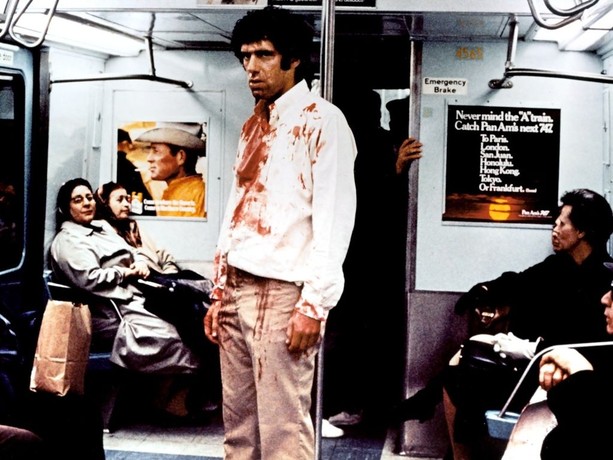

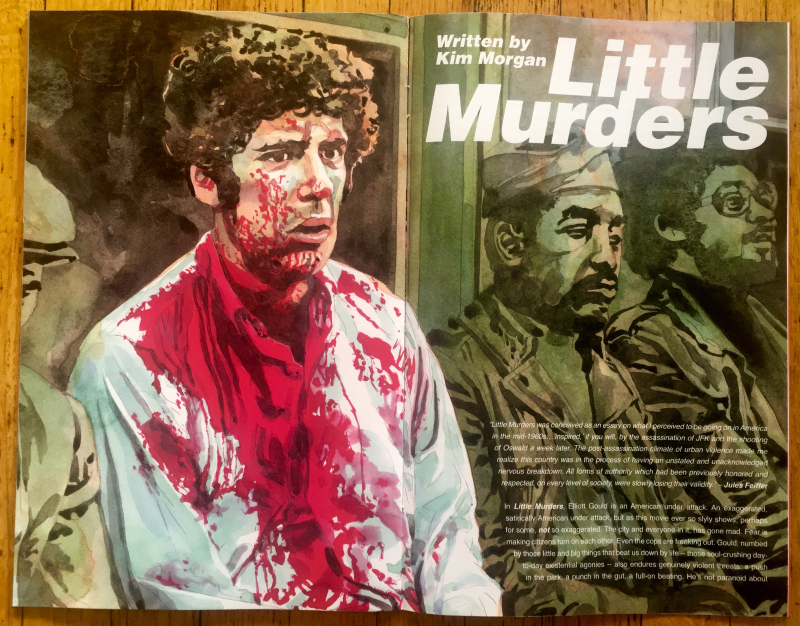

In Felix Feist’s The Threat, Charles McGraw’s Red sits in a chair in California desert shack – he’s leaning back. His feet are propped up on another chair – indifferent to the cast of characters freaking out around him – hot-placid amidst chaos. His sweaty partners in crime (Anthony Caruso’s Nick and Frank Richards’ Lefty) are pacing uncomfortably, wishing the beer wasn’t so warm (“Hot or cold it’s still beer!” Nick snarls to Lefty’s whining). They keep on the lookout. The tied-up men in the back – police detective Ray Williams (Michael O’Shea) and district attorney, Barker MacDonald (Frank Conroy) responsible for Red’s prior incarceration (Red busted out) – are strategizing and scared – and they look completely useless. What on earth are these straight-arrow fellas gonna do? What are they capable of – up against Red? Let’s see them try. Will they try?

The traumatized ex-girlfriend, Carol, who was forced along this dire road trip (Virginia Grey), the one who never ratted Red out and keeps telling him so – she is trying to keep her shit together and we feel for this poor soul. Red doesn’t believe her or the cops, and this slip of a woman (she is pretty, very distinct looking, but so thin she looks almost like she’s going to pass out), endures, vulnerable as all hell, but somehow stronger than the authority figures wiggling in the further room. She has a past with this man – you’d have to be vulnerable and strong to have a past with Red. And we’ll see more of that later.

The force of Red is so intense, so nearly unmoving, that everyone around him look like mice, circling an enormous cat – one who will casually swipe his paw and lay any one of them flat, maybe even dead. He’s ready to strike and yet totally relaxed – if that’s possible in a human. With McGraw it is. He doesn’t look comfortable necessarily, that’s not the right word, he doesn’t look like he’s enjoying himself either – he looks angry, but not out of control (just born pissed, something) – but he looks in his element, as if this was just what he was naturally meant to be and do and live in. Like he almost can’t help himself.

At this point, no one seems like they could take him (no one ever does, not really, until the end … keep your eye on skinny Carol), and all he really has against him is that old standby – time. So, when one of his partners claims that Red said they’d be out of there by daylight (it’s past daylight – and they’re worried and itching to exit this hell hole), the other asks for the time. Red rasps, “Give me your watch.” The guy (that’s Nick) takes his off watch and hands it to Red. Red puts the watch on the table, grabs a beer bottle, and smashes it. He chucks it back to Nick and says with his distinct growl, simply: “Now you don’t have to worry about the time.”

Well, indeed no.

This is a perfect Charles McGraw moment and one where you think – no other actor in the world would deliver that line the way he does. Even that simple of a line. None. Not even Lawrence Tierney, who never seemed like he was acting either. There is just something about this man’s voice and demeanor that is unmatched and reverberates through a room. Alan K. Rode, who wrote the ultimate biography on McGraw, summed it up beautifully in his book:

"His guttural rasp of a voice, reminiscent of broken china plates grating around in a burlap sack, was complemented by an intimidating, laser-like glare and a taciturn demeanor that verged on being closed captioned for the hearing impaired. McGraw’s brusque noir characterizations are comparable in technique to Thelonious Monk’s splayed fingers beating his unique jazz stylings into submission on the piano ivories. The title of Monk’s identifying theme ‘Straight, No Chaser’ exemplified McGraw’s artistic and personal bent for over half a century.”

In The Threat (1949) – Feist’s lean and mean story is told without an ounce of flab – filled out by the presence of the electrifying McGraw. The story is simple: Red busts out of Folsom Prison – we see this briefly at the very beginning – guys running, guns firing, sirens blaring, but we don’t need to see much else. The movie gets right to it. He’s on the run, and hell bent to get the guys who put him behind bars — that’s the District Attorney and the police detective who wind up in the aforementioned shack (one will get such bad treatment off screen, we hear his torment and truly wonder what on earth is being done to the guy – it’s more terrifying that we only hear his pained moans). They nab these two, nab sad Carol, nab a poor guy who has nothing to do with any of this, a guy named Joe (Don McGuire), and head out to the California desert hide-out, waiting for Red’s old partner to smuggle him into Mexico.

So, what’s going to happen? I’m not going to say because the joy in this movie is wondering how on earth anyone is going to get out of this place alive. And how are they going to take on McGraw? You wonder about the body count. You worry about Carol and you are riveted by Red. You can’t take your eyes off of him.

And so we watch – we watch the room rumble with McGraw's blood, his pumping black heart bouncing off those hate-shack walls. He’s casually savage, and for a moment, we might think he’s got something going on inside there – so if he briefly stares forlornly into the void, we look for some kind of feeling – and then wonder if he’s merely staring into a sociopathic abyss. McGraw’s Red, a furnace of vengeance, is boiling his captive's lives away by simply breathing near them. But, really, he’s boiling his own life away too – absolutely self-destructing. But he’s doing it his way. We guess. We wonder if this guy ever feels joy. He doesn’t seem too sad.

Everyone’s good to great here (Gray is a standout as are McGraw’s sleazy cronies), but it’s McGraw’s gruesome party all the way – from his silent menace to his terrifying bursts of violence (like pinning a man's wrists with his feet and crushing his head with a chair – one of the greatest scenes in the movie – emotionally and technically— and it was probably that same chair Red was so easily reclining) he is like nothing you’ve ever seen, and probably never will.

This is the movie that made McGraw something of a star – thought not a usual leading man – notably in Richard Fleischer’s Armored Car Robbery (1950), and The Narrow Margin (1952). And he did sometimes play a good guy – a tough guy but a good guy. He’s also terrific in Harold D. Schuster’s Loophole, Howard Daniels’ Roadblock, John Farrow and Richard Fleischer’s His Kind of Woman and of course, Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

Feist (who directed two other hellraisers, on and off screen – Lawrence Tierney in the tough, excellent The Devil Thumbs a Ride, and Steve Cochran in the rough and romantic Tomorrow is Another Day) working with cinematographer Harry J. Wild, knows how to showcase McGraw in such doomed digs. Tension builds so much that you can practically smell the sweat – and everyone’s sweat is a little different – you can smell that too. These characters perspire and dread and plan and panic and grow crazier and crazier while their big bad captor sits and waits, radiating wrath.

And all in just 66 minutes. That is six minutes over an hour for those who are bad at math. And during that time, this hysterical entrapment does not waste one minute of intensity, style, intelligence and Charlie-McGraw-magnitude. Feist knew what he was doing and who he was dealing with here. He knew who was the star (even though McGraw is third billed!)

And the movie needn't be shorter or longer. As if you were concerned about the time. Were you concerned about the time? Smash! “Now you don’t have to worry about the time.”