“So in ’67, we do this little motorcycle movie, Cameron Mitchell, the group of six, plus Miss Diane. We’ve got a little swagger under our belts. We’ve got ‘The Wild Angels’, which did okay. Jack has already done almost a decade of independent movies on his own, plus working for Roger. I’d been around almost a decade now. I’m a Kazanite, and so is Cameron Mitchell. We’re doing Roger without Roger. Marty Cohen doesn’t have a clue. There are some paying problems on this movie, but I’m standing by because my manager is producing it along with his friend Rex Carlton, who was dubious at best. At the end of the first ten days of shooting, they don’t have money for my actors. I’m going to get my money because my manager is the producer and director. That’s not right.” – Bruce Dern on “The Rebel Rousers”

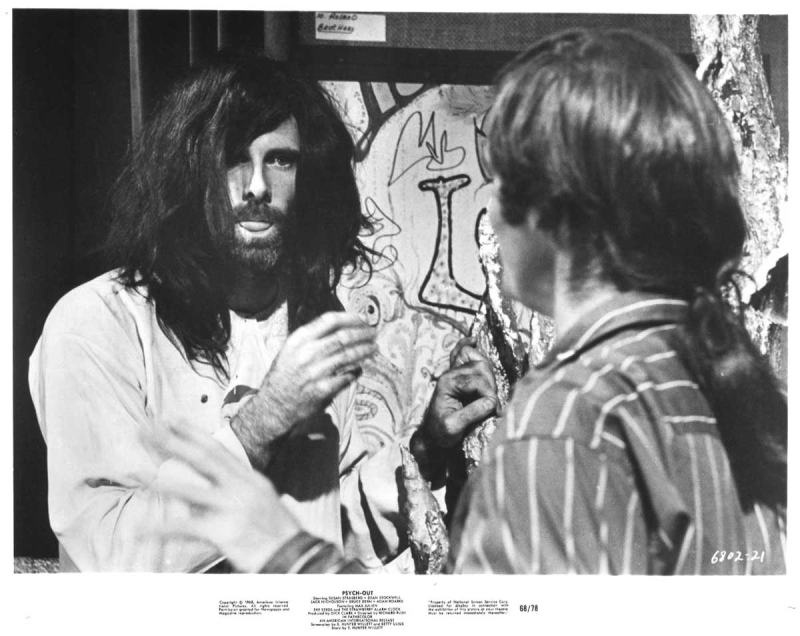

“It’s just one big plastic hassle.” – Dean Stockwell as Dave in “Psych-Out”

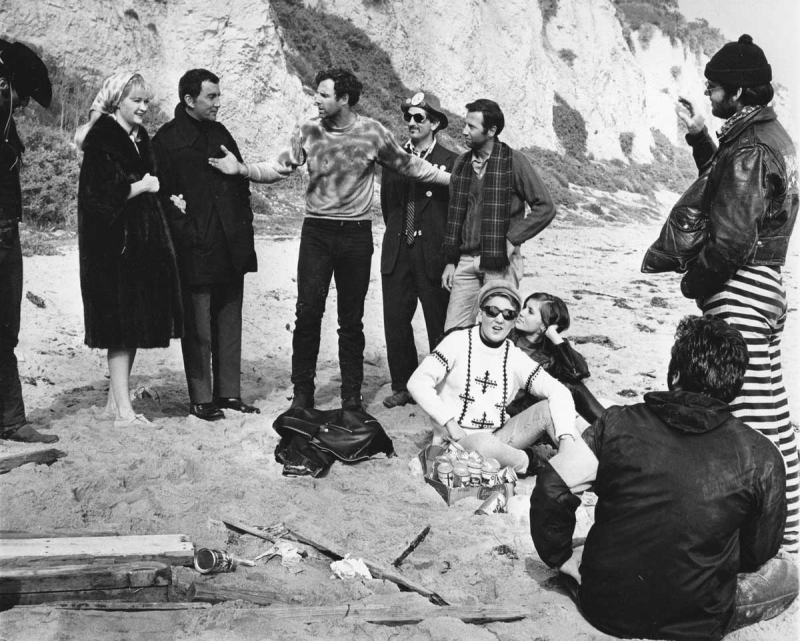

It’s 1967 and everyone looks a little exhausted. Fascinatingly so. I’m talking about the actors in Martin B. Cohen’s The Rebel Rousers and Richard Rush’s Psych-Out, both shot in ’67 – two very different movies, but two that have a similar vibe of … oh, we have done and seen so much already. We’ve been out of the house a long time, kids. But they are all creative – they’re all searching. They are all game – some are even quite powerful, and they seem real in spite of some hokey situations. No one is on auto-pilot. They’re all in their own world, but also, in it together, acting out something that could very well be happening internally, something a little darker, a little more vulnerable, something that’s responding to the 1960s nearing its end, something responding to their careers in a strange spot, to time marching on and time waiting for no one. This seems like a lot to say – especially for a picture that seems as inconsequential as The Rebel Rousers (Psych-Out has more going for it) – but there’s something in both pictures that reverberates beyond the movies themselves. In both, everything feels a bit off. And it’s not off in the way Rebel Rousers biker Jack Nicholson’s striped pants look (which are pretty great, really) or how Psych-Out hippie Jack Nicholson’s ponytail seems pinned on (also pretty great, if odd-looking), and it’s not the loud motorcycles and it’s not the groovy acid. It’s something else.

And, so, the actors’ tiredness feels appropriate, even, at times, moving. A moving bummer. But a kind of bummer that makes both movies infinitely more interesting. Is that the point? Do these actors feel all of this? Something darker going on? As pondered in Thomas Pynchon’s Inherent Vice: “Was it possible, that at every gathering – concert, peace rally, love-in, be-in, and freak-in, here, up north, back east, wherever – those dark crews had been busy all along, reclaiming the music, the resistance to power, the sexual desire from epic to everyday, all they could sweep up, for the ancient forces of greed and fear? ‘Gee,’ he said to himself out loud, ‘I dunno…’” I dunno. I dunno if these guys know either.

The Rebel Rousers (or Rebel Rousers) is a biker movie not directed by Roger Corman (The Wild Angels) or Richard Rush (The Savage Seven, Hells Angels on Wheels) but by Bruce Dern’s manager, Martin B. Cohen, his only picture as a director. It doesn’t have the energy of the aforementioned movies; Cohen’s craftsmanship is not at that level. I’m not sure if he knew what he was doing, though he had the benefit of working with cinematographer Laszlo Kovacs (who would also shoot Richard Rush’s Psych-Out), and of course, his excellent cast and, chiefly, Dern whose voice and movements and vocal inflections are transfixing. He can alternate from yelling gleefully to confused to sad to unsure to cocky to absolutely lost – he makes every moment count. But it’s intriguing to watch all of the film’s actors – Dern, Cameron Mitchell, Diane Ladd, Jack Nicholson, Harry Dean Stanton – they take their roles seriously, volley off of each other, and clearly, at times, improvise (you wonder what percentage of the movie is improvisation – how much script was actually written). As interesting as it is (to me, anyway, as a time capsule of these actors’ careers, as well as some mysterious kind of melancholy), it’s a slow-moving picture for those expecting crazier biker antics. And it contains some flat-footed offensive moments with the Mexican characters living in the town. It does feature a Mexican family (led by Robert Dix – son of famed actor Richard Dix) who eventually help Paul (he is seen frantically searching for help all over town without any success) and who face off against the bikers with pitchforks – but that doesn’t amount to much in terms of the story. Nicholson and Dern fight in a darkly lit scene (so dark I was wondering who was fighting – the striped pants helped) and Dern will find himself lost and a bit sad on the beach in a nice closing shot.

Here, the biker gang (including Earl Finn, Lou Procopio, Phil Carey and Neil Nephew) go about their wanna-be Wild One business, taking over a town (somewhat) and things get rowdy in a restaurant – they’re dancing on tables, women are taking off their shirts and shimmying in their bras, a guy plays the bongos, and they’re either scaring people or sort of charming them (there’s a moment where bad boy bikers Dern and Nicholson talk to an elderly woman who really looks like she was eating in that joint, I can’t believe she’s an actress and her little moment is kind of great – “She’s the woman of the year, man!” says Dern as he lifts up her arm triumphantly – she seems only mildly amused and certainly not shocked by them). But their rebellion is lackluster, tired. How many times have they pulled this crap? Aren’t they getting bored with themselves?

It seems like this is the point. They’re bored. These guys have nothing better to do than to ride in circles on the beach. The free-wheeling 60s spirit and outlaw attitude just seem like an effort here, even as being a biker is a ride-or-die way of life. Going around in circles seems to be the theme of the movie. As in, is that all there is? Had Monte Hellman directed (and he had already directed Nicholson, brilliantly, in two masterful westerns The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind, and also, earlier, Back Door to Hell and Flight to Fury), this movie could have been a fascinating existential rumination on … moving, on a road to nowhere (like the title of Hellman’s more recent picture). It’s nowhere near as interesting as anything Hellman would create (and certainly not as beautiful) but that rumination is there, albeit with less cinematic poetry. But, as said, Dern makes for a compelling character, particularly opposite Mitchell. He’s a guy who thinks he’s free but really isn’t. A guy who wants to be an outlaw but also wants to be good. A guy who probably secretly wants to hang it all up and settle down at some point even if he says otherwise. At the end of the picture, Diane Ladd (Dern’s wife at the time – she’s pregnant with their child, Laura) asks his lost biker, after all that has gone down: “Can we help you?” He answers: “No, it’s all right. I can make it myself. I think that’s kind of what it’s all about anyway.” I think he’s right – that is what it’s kind of all about. He thinks. He doesn’t really know for sure. Did Bruce Dern make up that line? It’s a good one.

“‘Gee,’ he said to himself out loud, ‘I dunno…’”

When the movie begins, Dern, as biker leader J.J., and his biker crew (including Nicholson as Bunny, wearing those striped pants, and Stanton as a guy who wears a tricked-out suit – he looks nothing like a biker, which works well for his character in this kind of cool yet ironic attire) have ventured into the small town, ready for mischief. Dern bumps into a guy he played football with in high school in Los Angeles – the architect Paul Collier (Mitchell – who is over 15 years older than Dern, so Dern is either supposed to be in his late 40s or Mitchell in his early 30s – or both of them somewhere in between). Paul is about to have a tense reunion with his pregnant interior decorator girlfriend, Karen (Ladd), who sits nervously in a hotel room. She wears a fur coat and carries a Chanel purse. She’s neither outlaw nor hippie. Dern and Mitchell exchange pleasantries – and they really are being pretty nice to each other, even as Dern is calling Mitchell out as something of a square, albeit, gently, but Mitchell doesn’t seem to care. He’s eager to find Ladd. The two men quickly catch up on what each are doing. Dern says, vaguely, “Oh, I’m around, getting by, finding out where things are at.” He invites Paul to hang out later, and rides off, and Paul goes to the little motel Karen’s staying at. They have a lot to talk about. Chiefly, is she going to keep the baby? Are they going to get married? It’s a strange centerpiece to the movie – this couple attempting to figure out their lives and maybe bringing a child into the world together, as a biker gang has entered the city and will, in no time, terrorize them.

And they do terrorize them. As Paul and Karen take a drive to talk, the bikers (sans Dern) jump up on their car and start hassling the couple. Dern breaks it up in his attempts to be a peace-maker, a nice guy (again, he went to high school with this fellow, they played football), and they take the couple down to the beach. It all starts going crazy when Bunny wants Karen for a night and is not taking no for an answer – Dern’s closest pal here is being just too much of a predatory rapist scumbag. So, in both a twisted game and an attempt to stall for time (this way Paul, who has been beat up, can run and get help), a race is proposed to win Karen. This isn’t exactly a comforting scenario for Karen and you do worry about her – there’s very little titillation presented in this scenario. You also feel for Paul (Mitchell has some incredibly believable moments of desperation, he’s a wonderful actor). But there’s something so banal about how these outlaws mess with the couple – but because of that lack of excitement, it feels like how something like this would go down. Nothing cool or exploitative-sexy about it. It’s a bunch of yahoos scaring this poor woman with Dern’s J.J. feeling guilty while being something of a coward himself. We are feeling it – something Dern touched on in his autobiography. He said of the movie:

“There is some pretty goddamn good acting going on where things are flying around and people are into moment-to-moment behavior and everybody’s getting chances to do things with a beginning, a middle, and an end to each character in each scene, and nobody’s getting away with anything. There are no star trips going on. Each one of us threw ego out the window and tried to make a movie that made sense. Out of that came a sense of dignity from me and my character just trying to keep from drowning, holding it all together in front of and behind the camera. It was pretty exciting work when you consider it was total chaos.”

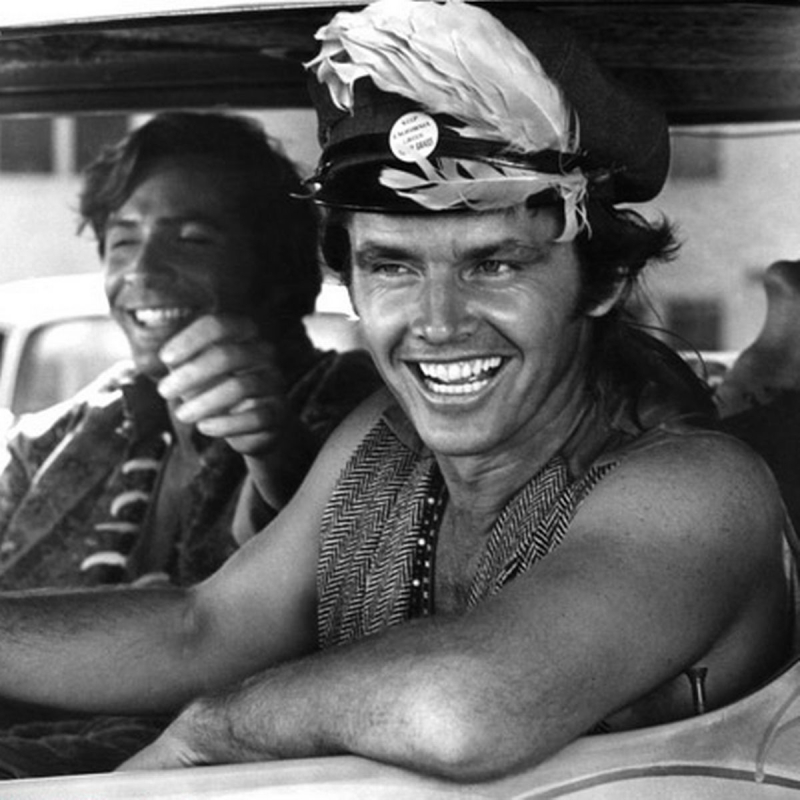

He’s right. But no one releasing the picture was grooving on the film’s slow moving middle-aged story about a couple arguing over a baby and possible marriage while bikers terrorize, no matter how great the acting, and the picture was shelved. It was released three years later in 1970 after Nicholson broke out as a star from his memorable turn in Easy Rider and about a few months before Five Easy Pieces (one of his greatest, most defining roles) was released. If anyone went to see Nicholson, however, they got a lot more Dern and Mitchell (and they are both terrific here), but Nicholson stands out as a goofy crazy sinister guy, clearly ad-libbing a lot of weird dialogue. You can’t take your eyes off him. Nicholson has been around a long time, but he’s incredibly creative – on screen and off. And Nicholson, according to Dern, had a lot going on, personally. This was also a tough, transitional moment for Nicholson, some major life changes had put him in a melancholy mood as he was shooting the picture. From Dern’s autobiography:

“I would walk down the beach when we were shooting at Paradise Cove. Sitting between two huge rocks, frustrated, very touchy, down, sad, and angry, was Jack. Tearful some days. Depressed most days. He was going through a divorce from his wife, Sandra, who was the mother of their daughter, Jennifer, who couldn’t have been more than a year and a half old. Jack could still rise above it all, even though he was terribly wounded. I had a love for him from that time on and would do anything to help him out. He was writing a script, The Trip, with a part that he intended to play himself … I’ll never forget that day, when I saw a wreck of a guy writing that script because of the circumstances in his own life, the emotional grips that were on him, the frailty of the human being. I fell in love with Jack, and I realized what an amazing guy he was. My heart went out to him. Then we turned the switch on ten minutes later, and he was there, take after take after take, rising above his own problems.”

Nicholson did indeed write The Trip, but he didn’t get the role he had written for himself – that went to the guy who felt for him all depressed on the set of Rebel Rousers: Bruce Dern. As discussed in Dennis McDougal’s, “Five Easy Decades: How Jack Nicholson Became the Biggest Star in Modern Times”: “Jack wrote a part for himself as Fonda’s guide through the psychedelic wilderness, but Corman awarded Bruce Dern the role instead, having lost faith in Jack’s screen charisma. Although Jack was Dern’s acting equal, other directors wouldn’t hire him, and Corman joined their ranks. He began to think of Jack less as an actor and more as a writer. Dern concurred. ‘The original script that he wrote for The Trip was just sensational.’”

Peter Fonda said even more. From McDougal: “’I don’t believe it,’ a weepy Peter Fonda told his wife, so moved was he when he first read Jack’s script. The Trip ranked with the best of Fellini, he said. ‘I don’t believe that I’m really going to have a chance; that I get to be in this movie. This is going to be the greatest film ever made in America.’”

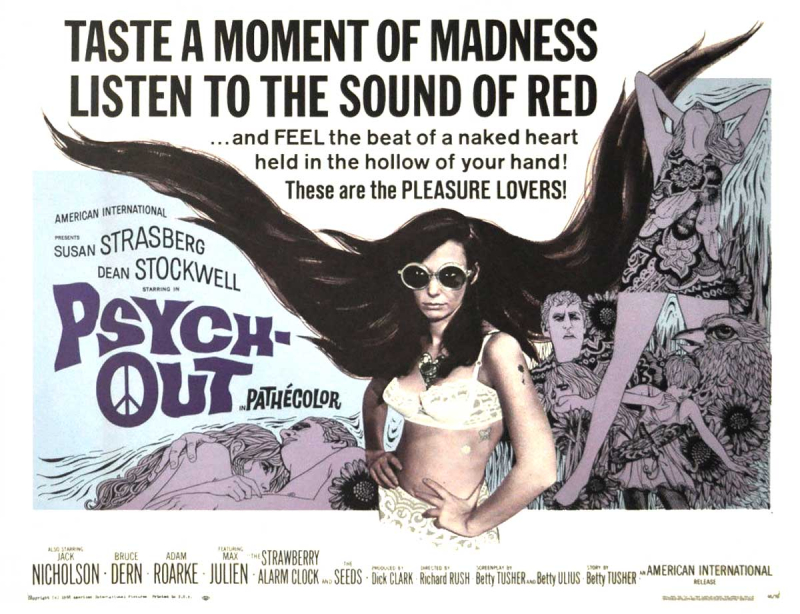

The movie Dern and Fonda read was not the movie that was, in the end, made. What Nicholson wrote in that script changed significantly once Corman got a hold of it, excising entire scenes and storylines. But the movie became a big hit for Corman, leading to Nicholson writing Psych-Out. Nicholson completed the script in May of 1967, with the title Love is a Four Letter Word. According to McDougal, producer Dick Clark didn’t like that title and changed it to The Love Children, and then Samuel Arkoff, didn’t like that one (he thought it sounded like illegitimate children), and so it was changed to Psych-Out – an ode to Psycho, which only makes sense in terms of the re-release of Psycho (at least Clark, I’m assuming, got some great music acts on the soundtrack – among them, Strawberry Alarm Clock and The Seeds). The script was changed so much that Nicholson’s name was taken off of it. He did get the lead role, this time, however, as Stoney.

So here we have Stoney and his rock band, Mumblin’ Jim (with friends and bandmates, Ben, played by Adam Roarke, and Elwood, played by Max Julien) living in Haight-Ashbury, just hanging, getting high, playing music, seducing women. A deaf runaway, Jenny (Susan Strasberg – who was also in The Trip), shows up in their coffee house one day – and Stoney is attracted, or at least wants to sleep with her. There’s already a lot more energy to this movie over those doleful bikers in Rebel Rousers – these guys seem to be having some kind of fun, at least in bursts of pleasure with one another (who knows how long those bursts last), and thanks to the presence of the immediately likable and wonderfully natural actors’ Roarke and Julien. And Richard Rush is a far better director, a guy who understood and discussed being anti-establishment (expressed so much better in his powerful Getting Straight starring Elliott Gould. Rush also directed the great Freebie and the Bean and the masterful The Stunt Man). He also works nicely with Laszlo Kovacs, achieving some beautifully shot moments, and fascinating documentary-style footage of the scene. But, just as in Rebel Rousers there’s an edge of … when is this all going to end? This all can’t last. Stoney and Ben and Elwood are nice to Jenny (even when Stoney tries to prove her deafness to his friends by saying, “Let’s kill her and eat her” – what a line, and with Nicholson uttering it – I can never forget that line) and they hide her from the cops who’ve come in looking for her. She’s ditched home to find her brother Steve (we will learn he is Bruce Dern, crazy-eyed and poignant here – and he is now a kind of mysterious character known as “The Preacher”).

So, she shacks up at the communal crash pad where Stoney sleeps (and eventually becomes frustrated by their way of living – no one does the dishes) and follows along with some of these guys’ adventures, observing weirdos, watching mock funerals (where the The Seeds appear and play) and meeting philosophical dudes (chiefly, Dean Stockwell, as Dave) along the way. Henry Jaglom plays an artist who completely freaks out on drugs and tries to cut his hand off with a power saw. He hallucinates Stoney and friends as walking corpses. Jenny asks, somewhat sensibly at that moment (he did try to cut his hand off, after all, but one never knows how a trip will go), “Why does he take that stuff?” Stoney answers: “Don’t judge people, Jenny.” And then another guy starts lecturing her about Nietzsche – she walks off. Her brother is “The Preacher.” She doesn’t need any more of this shit.

Stockwell is Dave (I love how simple that name is), the ex-Mumblin’ Jim band member who dropped out because they were too focused on making it. He doesn’t dig that kind of ambition – that kind of ambition that Stoney has – and Stoney is a rather single-minded guy, but it’s hard to blame him seeing as how some of this scene may end up. Cynically, it’s going to probably get bought up or darker forces will enter the fold, so why not get famous? Maybe he can call the shots then? Maybe. He may sleep around and get high, but he’s got some priorities and organization and, deep down, you sense this guy doesn’t want to crash in a dirty house much longer.

Everyone seems on the cusp of moving on to something else – not necessarily all for the better. Stoney will maybe become famous, or at least, as said, he’ll be striving for it, make a living from music, and Dave just seems like he’s going to … well, he’s going to, by the end, die, actually. His dying words are quite touching: “Reality is a deadly place. I hope this trip is a good one.” And so Dave, though his heart is in the right place, he’s not going to sell out, he’s going to live life on his own terms. It’s interesting to watch Stockwell – he’s waxing philosophical about everything, and he’s critical, but he seems like walking death throughout the movie because it’s going to be hard to really live like that. Stockwell plays this not like a naïve youngster, but as a guy who has been around the block, a guy who is hanging on to his philosophy before he’s killed off. When Stoney asks Dave to play with their band again, he turns them down. “Truth” is brought up:

Stoney: We need you to play with us.

Dave: You still playin’ games, Stoney?

Stoney: Since when is music a game. Playin’ makes me feel good.

Dave: So does a paycheck.

toney: Oh, yeah. The old bad thing. The root of all evil, right?

Dave: No. Not bad or good. There’s only the truth.

Stoney: The truth. Old black and whitey.

When Nicholson wrote the script, he was experiencing his own kind of journey, with LSD, with life, with acting, with his creativity, with “New Hollywood” (he would go to direct his impressive directorial debut, Drive, He Said, released in 1971 – read J. Hoberman’s excellent piece about that and BBS productions formed by Bob Rafelson, Bert Schneider and Stephen Blaune, from Criterion) and it would have been interesting to see his original work. From McDougal’s book:

“Jack became a Reich devotee in the late sixties for the same reasons he dabbled in Krishnamurti and LSD: to get to the core of his creativity. In conversations with Strasberg during the filming of ‘Psych-Out,’ Jack admitted that his ‘volatile field of energy’ made him hard to live with. He called himself ‘an existential romantic’ pursuing life, liberty, and orgasmic release … As a result of Reich, ‘I don’t falsify sensuality,’ Jack declared. But neither was he just another horn-dog hedonist. Jack’s evolving beliefs still left plenty of room for monogamous intimacy. ‘You can feel the difference when you make love and there’s love there, and when you make love and there’s not love there,’ he said. ‘I’m not a Victorian, but a fact’s a fact.’”

A fact’s a fact. Old black and whitey… But you get the sense that there was a vibe on set that was seeping into the production. These actors, all of them great actors, have worked so much already, they’re neither young nor old, they are indeed, New Hollywood, and they’ve seen and experienced so much that you can feel the sad cynicism of Easy Rider approaching – and this spirit will seep into even more creative, thoughtful work in the 1970s. Are these guys gonna be free? You see Peter Fonda as Captain America thinking – his ambivalence – while starring in and creating one of the iconic films of the late 60s, and one that is leading us right into the 70s. The shooting of Psych-Out expressed a kind of change-over as well. According to McDougal, there were those in the area who weren’t cool with the production, those that interrupted all of this free and easy peace and love, and director Richard Rush had to turn to a real-life Rebel Rouser for help:

“During filming, Rush again called on Sonny Barger, but this time not for his technical assistance. After panhandlers pulled knives on the cast and crew, Rush hired the Angels to patrol the shoot. The Summer of Love had ended by the time Rush’s cameras rolled in October 1967, and Clark observed that a ‘tougher element’ had taken over the Haight. By the time ‘Psych-Out’ was released in March 1968, peace, love, and understanding had given way to paranoia, lust, and heroin. In the pages of Variety, Clark predicted that hippies would soon fade across America, not just in San Francisco.”

What a bummer. But what an interesting bummer. Because these actors and filmmakers are about to move on to some incredible art and careers, some of the most defining work of the 1970s. But after watching these movies, I’m again thinking of Diane Ladd in Rebel Rousers asking Bruce Dern: “Can we help you?”

“No, it’s all right. I can make it myself. I think that’s kind of what it’s all about anyway.” Kind of. Because you, everyone, always needs a little help.

Originally published at the New Beverly