From my piece published at the New Beverly.

“Questions arose. Like, what in the fuck was going on here, basically.” – Thomas Pynchon, Inherent Vice

I love watching Robert Mitchum amble around His Kind of Woman with that particular walk of his, navigating this schizophrenic maze of a movie like it’s a typical day in the life of … Bob Mitchum: Light up a reefer, what’s Jim Backus up to? What the hell does Charles McGraw want? Millionaire but probably not a millionaire Jane Russell is wooing that actor Vincent Price playing an actor. Fine, fine. We’re all friends. Or enemies. Who knows? Guess I’ll mingle.

Mitchum never lights up a reefer in the movie, he doesn’t even drink (he has milk in one scene, orders ginger ale in another) but you can imagine it happening off camera. And, again, he does saunter with his special kind of physical cool – that walk he found baffling for being so “interesting” to people. His response to that? “Hell, I’m just trying to hold my gut in.” Well, this movie isn’t trying to hold its gut in, and if it ever had any intention to, it abandoned that mission and went on a manic munchie binge, unbuckled its belt, and let it all out. And then took another hit. His Kind of Woman might not have been made to be a movie with marijuana in mind (though Mitchum was busted for it in 1948 – did two months’ time and was released in 1949) but this is a pot-smoker’s movie, a stoner noir with a knotty plot and loads of characters doing weird shit – characters who seem, not just stoned, but who make you feel stoned once you settle into the thing.

This is a movie where our lead actor hangs around for nearly an hour before he really figures out just “what in the fuck was going on here, basically.” He’s in a John Farrow movie, a Richard Fleischer movie, a Vincent Price movie, a Howard Hughes movie, and a Howard Hughes movie that, off-screen, is obsessing over the details like the eccentric billionaire instructing an assistant on how to properly open a can of peaches.

When I quote Pynchon, it’s not just a joke, this feels like Pynchon, a world Doc Sportello would stumble upon, putting the pieces together with his Doper’s ESP because, sure. What does this all mean? There’s the German writer Martin Krafft (John Mylong), always in dark sunglasses who plays chess with himself but is actually a plastic surgeon for Raymond Burr’s moody mobster Nick Ferraro. Mamie Van Doren, not as Mamie Van Doren but it doesn’t really matter, shows up for a second. I mentioned Jim Backus. He’s a creepy investment broker named Myron Winton who is trying to gamble away a recently married young couple’s money, presumably to take off with the bride. Nice try, Backus. No dice. A bravura Vincent Price is a crazed actor named Mark Cardigan and not just a crazed actor in the usual sense but a game-hunting crazed married actor having an affair with Jane Russell and one who will become so amped up with adventure and bloodlust that he really starts shooting bad guys, announcing things like, “I must rid all the seas of pirates!” He’s so intoxicated with what he’s doing that he literally shoves Jane Russell in a closet – she may be pretty but she can’t help him and worse, she’s a scene stealer.

This is a movie where Mitchum irons his money. When he runs out of money he irons his pants.

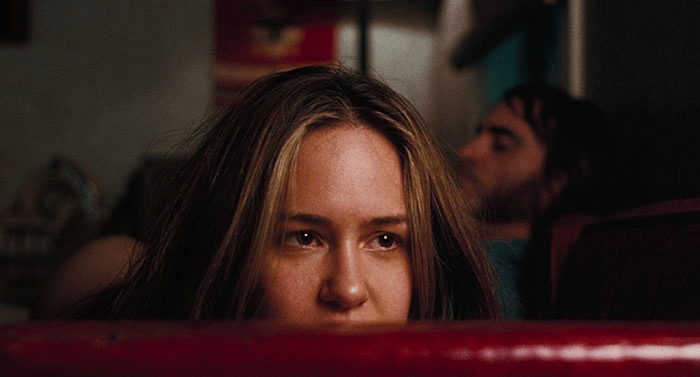

Money-ironer Mitchum is gambler Dan Milner (he has such a normal name), who has just been sprung from a month in jail and, with little prospects, accepts a shady deal. It’s $50,000 to head out to Mexico, presumably for a year, no idea why. Well, why not? He needs the money because he owes money, naturally. He does not appear to have much else going on other than that he’s Robert Mitchum. He’s flown away and meets beautiful, supposed rich girl, Lenore Brent (Russell) in a Mexican cantina while awaiting his next plane, where she charmingly sings “Five Little Miles from San Berdoo” and insists only on champagne. They wind up in the same plane together and off to the same impressive, crazy-ass resort – a play land for cops, gangsters, actors, German novelist plastic surgeons, Jim Backus, I’ve already said this … And then the movie really gets to ambling around, with Mitchum’s Dan trying to figure out what is what and who is who and who to trust inside this surrealistic alternate universe.

He meets almost all of the aforementioned people (and more) at a gorgeously constructed Mexican resort called Morro’s Lodge, an enormous, modern tropical retreat – a set built for the movie that really could be a resort. The sharp modern angles amidst all the lushness and curvaceous philodendron leaves add to the film’s surreal atmosphere — it was even created with its own beach. The rooms have low ceilings (or maybe they just seem lower when Mitchum’s standing in them) and everything looks gorgeously off — like a place you’d love to hang out at but a place that could drive you crazy. A glorious hideaway with a fake beach. Since we’re going to spend a lot of time in this glorious hideaway, John Farrow (with cinematographer Harry J. Wild) showcases the lodge in a stunning, dreamy single take that floats through the place in all its clean-lined glory, bustling with guests, until it lands on Mitchum. He enters with that walk of his, looking sharp. But… dig this place. He both fits in and doesn’t fit in. Kind of like everyone else here.

As mentioned, Price’s crazy Mark Cardigan is enjoying the lodge, hunting, and having a romance with Russell’s Lenore who is, guess what? She’s not actually rich and is gold-digging Cardigan, but she’s still likable and never presented as the fatale, which is a refreshing aspect to the story. She’s using him? So what? He’s using her. And she’s amusing about it. And Milner likes her – a lot – their chemistry (also seen in another Mitchum/Russell/Hughes RKO picture with two directors – Macao) is so sexy and witty, with banter so sharp but good-natured, that you absolutely buy Mitchum having no problem being pals with a woman he’s sexually attracted to. (Friends in real life, this adds to their buddy allure). And they both stay friends with Cardigan who is … well, he’s narcissistic and nuts, and maybe even dangerous, if you step in a boat with him. Since Price was quite fond of both Russell and Mitchum, we buy all of this too. Who else are they going to hang with out there? On top of this, Cardigan is having the most actorly mid-life crisis breakdown you’ve ever seen, and it’s just too entertaining for both the audience and perhaps Milner to not take it all in.

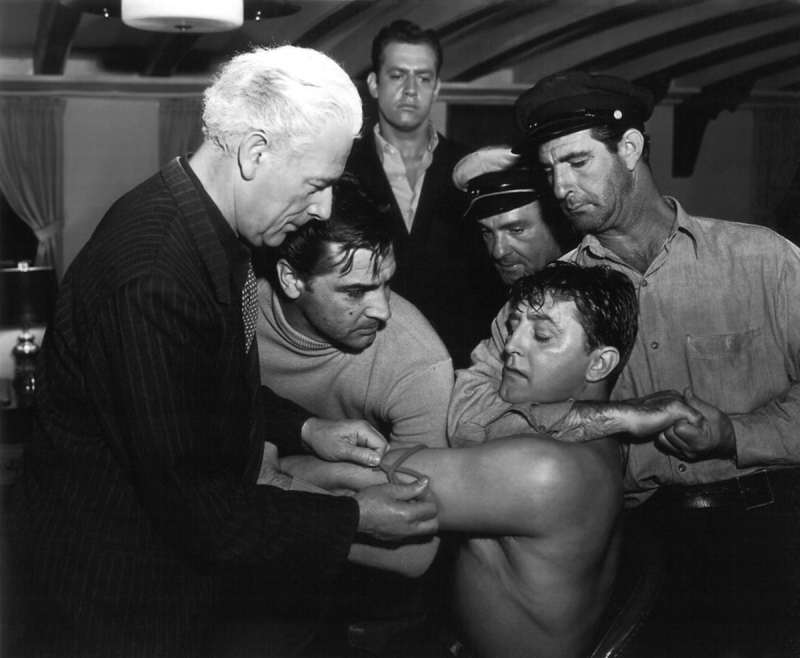

Cardigan takes over everything – and the movie shifts with him, pushing this tonally strange noir over the edge into pure comedy, or a feverish satire, mixed with an extended, sadistic almost homoerotic beating served to Mitchum on Ferraro’s yacht. That beating is quite something – Mitchum shirtless and suffering and injected – and it goes on and on and on while Price’s Cardigan is out to save him, donning a cape, manning a boat, quoting Shakespeare and all. Mixing comic relief with this kind of brutality is almost bracing – one minute we’re howling over Vincent Price hamming it up to high heaven, the next we’re wincing at poor Mitchum, looking Saint Sebastian-like, as he’s going to pass out from pain.

But before all that pain – before Milner learns why’ll he’ll endure this kind of pain, there’s Charles McGraw as the heavy, Thompson, who needs to be mentioned because he’s just kind of wafting around the edges of this movie. He’s mixed in with Krafft and Ferraro, but Dan doesn’t understand the extent of this until a maybe drunk guy (Tim Holt) lands his plane at the resort (this is a Howard Hughes movie, after all) and fills him in. That guy tells him he’s an undercover agent for the Immigration and Naturalization Service, because, of course. And then Milner learns the truth – bad guy Raymond Burr wants his face. He needs to get back into Italy undercover as Milner, and I guess it’s not so hard to attach Robert Mitchum’s face to Raymond Burr’s body. At this point you may feel like you’re dreaming, and not just because of the plot, it’s just the overall vibe and spirit of the movie. You follow along with the loony path of Cardigan – who, in an almost meta performance, takes this whole thing AS a movie he’s starring in. Even quipping about the movies in a near death moment.

Milner: I’m too young to die. How about you?

Cardigan: Too well-known.

Milner: Well, if you do get killed, I’ll make sure you get a first-rate funeral in Hollywood, at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre.

Cardigan: I’ve already had it. My last picture died there.

And Milner almost dies. That beating – it is vicious and kinky by 1951 standards, and extra strange because producer Howard Hughes wanted more of it. The production and post-production dragged on when John Farrow was excused by Hughes, and replaced by Richard Fleischer, who added scenes and re-shot scenes, including the beating and more (more!) Vincent Price – a great decision if you dig how loony this picture turns out to be. (And you should – Price is fantastic.) He also cut the original actor playing Ferraro and cast Raymond Burr, with Fleischer re-shooting all of his scenes. Lee Server’s excellent biography on Mitchum, “Baby, I Don’t Care,” has an amusing, absorbing rundown of this exhausting production, particularly regarding Hughes’ constant tinkering, and how Mitchum eventually soured, and turned to extra drinking. From Server’s book, actor Tony Caruso said of the beating scene, “Hughes was sending all these messages, ‘Do this, do that. Have Caruso hit him harder. Hit him in the gut. I want to see his fist go in deep’ – all that kind of crap.” And then there’s this instance of Hughes’ obsessiveness, which seemed to seep into the bizarreness of the film itself. Via Server:

“Of all the newly invented material, Hughes had become most excited by the scene in which an ex-Nazi plastic surgeon offers to dispose of the Mitchum character with an injection of an experimental drug. Hughes declared that he would write the dialogue for this scene himself, and to Fleischer’s amazement Hughes not only wrote it but sent along an acetate recording of himself speaking the German doctor’s lines in a high-pitched TexaBavarian accent.”

Wow. Talking experimental drugs in a “TexaBavarian” accent. Perhaps Hughes should have cast himself as the doctor with the dark glasses – or at least dubbed in his voice to make this movie even extra gloriously topsy-turvy. You’d think the actors might look nervous, even, at times, besieged on screen, given how long this production went on, but they don’t. None of them. When in Rome? And Mitchum glides through this groovy quagmire with his cool and hunky grace intact, nary a trace of effort – surviving Raymond Burr, surviving that Nazi doctor, surviving Howard Hughes. I’m blurring the work of Howard Hughes into the story like he’s an actual character in the picture – but the more you learn about the production, the more you feel like Hughes is one – hiding out in one of those rooms at Morro’s Lodge, worrying about more than the door handles. His Kind of Woman was His Kind of Movie – and for all sorts of strange, stoned reasons – it works. I exult in its cracked, inebriated wonder. As Cardigan says, “This place is dangerous. The time right deadly. The drinks are on me, my bucko!”