Helen: I don’t like to wake up alone.

Bobby: I don’t want you to. But it happens sometimes.

The smallest thing can change a life forever. In the case of Jerry Schatzberg’s The Panic in Needle Park, it’s a scarf. A thoughtful moment in which one stranger gives a shit about another, and just for a mere few seconds, the stranger’s scarf warms the young woman who lies shivering on a bed, bleeding, in full view of her insensitive boyfriend. It’s a much-appreciated gesture of kindness after this woman has sat cold and in pain on a grim subway ride after having an abortion. There’s something extra sad about a woman taking a subway back, alone, from such a procedure (no one came with her? Did she want to be by herself?) and writers John Gregory Dunne and Joan Didion well understand this (think of Maria’s trip to the abortionist in Didion’s Play It As It Lays, the novel and in Frank Perry’s movie). We don’t know what’s happened to this woman when we first see her in that tube, but that she looks troubled and in pain, emotionally and physically, as she hangs on to the pole. She’s grateful just to sit down once the crowded passengers exit to the next stop and she catches her breath, looking not just sad but . . . this is my life right now. That kind of a look. It’s not a long scene, but it opens the film – a solitary woman likely thinking of her bloody, gunky insides that could have held a baby, whether she wanted the baby or not, and wondering how she’s going to get through this, as she speeds along surrounded by glass and metal and plastic, full of people thinking of their own lives.

The scarf is a bonding, romantic moment for a lonely person, she can feel a part of him as she nestles it close to her face. Lonely people need each other – that’s a given – but according to many theories, lonely people, when given the opportunity, feel they need drugs, and more and more drugs. Johann Hari, who wrote “Chasing the Scream: The First and the Last Days on the War on Drugs,” wrote about such studies, citing Professor Peter Cohen who argued that “human beings have a deep need to bond and form connections. It’s how we get our satisfaction. If we can’t connect with each other, we will connect with anything we can find – the whirr of a roulette wheel or the prick of a syringe. He says we should stop talking about ‘addiction’ altogether, and instead call it ‘bonding.’ A heroin addict has bonded with heroin because she couldn’t bond as fully with anything else. So the opposite of addiction is not sobriety. It is human connection.

That young woman on the subway, Helen (Kitty Winn), will become connected to the young man with the scarf, Bobby (Al Pacino), pulled in by his sweetness and charm, his streetwise beauty, his bad boy strut that’s overcompensating a bit – he needs to seem tougher and cooler than he is – and eventually she’ll be seduced by the heroin that’s keeping him together. The drug will rule everything in their lives, where they live, how they work, who they’re friends with, and the effects of the drug, that warmth that spreads through you and cradles you into narcotic consolation, must be there. You feel adrift and alone enough, the overwhelming hug of heroin becomes more important than your boyfriend’s hugs – and if your boyfriend is doing it too, he understands the persistent need – he needs it too. So finding your drugs and fixing each other makes you the Bonnie and Clyde of junk, bonded, together until the end, you think. Until the stuff makes you rat the other one out.

Bobby not only gives Helen his scarf, he visits her in the hospital (“I come for my scarf” he says sweetly, not at all coming for his scarf but to see this “terrific looking chick” again). The bleeding has become so bad that she checks herself in and she lies in bed thinking of her next move. Fort Wayne, Indiana she tells Bobby, that’s where her family lives. Presumably, she’s at the end of her rope in New York City, dating an artist (a memorable Raul Julia in a small role) and hobbling to the emergency room by herself. But Bobby’s outside the place waiting for her (sometimes that means nearly everything if someone is simply waiting for you) so when she walks out of the hospital and sees him there that is . . . it. She’s fallen for the guy. The Panic in Needle Park is, after all, a love story, and the beginning of Helen and Bobby is poignantly romantic, the sincerity of how Bobby (the way he looks at her with his beautiful brown eyes) feels towards pretty Helen who looks like a “nice” girl (the idea of what that means anyway), the quiet, artistic girl everyone probably had a crush on in high school. Helen’s a little more complicated than that stereotype, just as Bobby’s not merely the bad boy, he’s not just a nice guy either, and the performances by Winn and Pacino get that – they are everyday people and addicts and they are absolutely compelling to watch

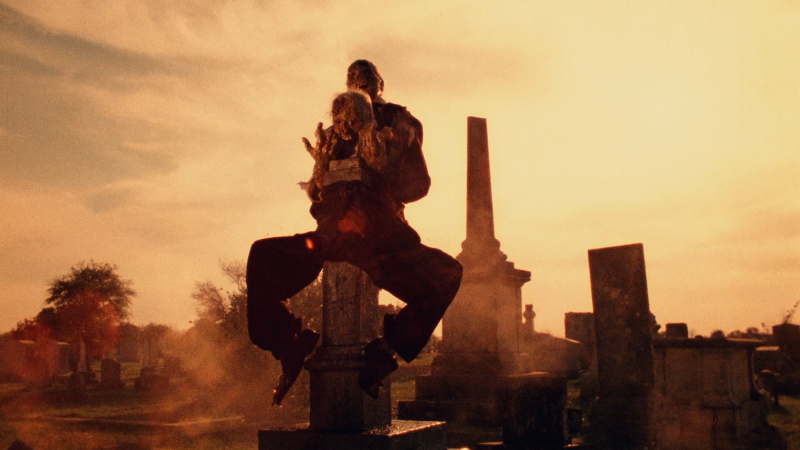

Schatzberg’s gritty, documentary-style picture, his second movie (shot with cinematographer Adam Holender, who also shot Midnight Cowboy), doesn’t flinch from the needles in arms, crying babies rolling on seedy mattresses and wiped-out junkies, of all ages, passing out on park benches or mumbling about election years causing the panic of product (“What election?” “I don’t know man, some election.”) Schatzberg had done a lot of living himself at that point, an acclaimed photographer of fashion, street and portraiture (he famously shot Bob Dylan’s cover of “Blonde on Blonde”), the man had snapped everyone from Edie Sedgwick to Andre De Toth to the Rolling Stones to Phil Ochs to LaVern Baker and more. His first film, the striking, experimental character study about a troubled ex-model, Puzzle of a Downfall Child, was based on a model he knew and starred an actress he also knew quite well, and shot beautifully (an excellent Faye Dunaway). With Panic, the director showcases his talent for street photography and filming faces and (as I stated in my piece on his third film, Scarecrow), he loves Pacino (this was Pacino’s first starring role, and it’s brilliant). Pacino’s gum smacking, his expressive face, his charm that’s sometimes dumb and sometimes tender, his anger, his guile, his doped-out stupors – it’s all expressed in a performance that’s both touching and maddening. And likable. You get why Helen is drawn to him. And you get why he’s drawn to Helen. Winn, wonderfully understated and a little shy, has those faraway eyes that evoke, simultaneously, a fresh start and some kind of terrible past. They both look like people you might know.

In an interview with Dazed, Schatzberg was asked about the picture’s unflinching realism. He said: “At that time in New York in the 70s, you could see people shooting up in the alleyways. Joan Didion and John Dunne adapted the book ‘Panic in Needle Park’ for the screenplay [by James Mills]. Needle Park was Sherman Square, at Broadway and West 70th, and it was popular because it was where young white addicts could get drugs without going to Harlem. Keith (Richards) was funny – I knew the Stones, I’d photographed them a lot, once dressed as women – and they were in Cannes when I was there with Panic in 1971. Keith said to me, ‘Hey, are you on the hard stuff?’ pointing to his arm, and I said ‘No.’ He said, ‘Then how come you can make a film like that?"

Schatzberg made it by observing other addicts (with Pacino), and probably from people he’d met shooting and running clubs, and, as a great photographer, simply looking at life around him. He shot it in Sherman Square (called Needle Park) where the film’s junkie family congregates, going on about their own dramas and stories, present and past, telling, often, banal stories or talking nonchalantly about things that would shock others with horror. The lifestyle and this family start catching up with the couple and Bobby’s burglar brother, Hank (an incredible, creepily handsome, lizard-looking Richard Bright) wants Bobby to work with him after Bobby intends to marry Helen (this is after she starts shooting up, I guess Bobby thinks this makes it official). Helen tries to work at a diner (she’s useless, she can’t get hot chocolate and jelly donuts right) and she walks off the job. A lot happens – Bobby ODs and almost dies, he gets arrested, he starts handling distribution (a big deal to him), Helen sleeps with Hank (she tells Bobby later who really wishes she’d kept that information to herself), and Helen hooks. As all of this is happening they’re under the eye of a Narcotics Detective, Hotch (Alan Vint), who keeps telling Helen that all junkies will eventually rat each other out and he encourages her to rat out Bobby. Hotch always seems to be there, not just to bust them, but to puncture the romance, the whole idea of together, forever – in dope sickness and in health.

After a lot of hell, and with future hell ahead of them, they buy a puppy, and you know that poor puppy isn’t going to have a normal family life, or a long life for that matter. Roger Ebert, who lauded the movie, didn’t like the puppy bit at all and wished the film had axed it. I’m not sure why, other than it’s a heartbreaking interlude on a ferry where, yes, after Bobby and Helen fix in the bathroom, the puppy jumps off the boat and drowns. Helen cracks and who can blame her? It’s certainly obvious Helen wants that puppy for something innocent and warm to hug, another form of family, another creature to stave off loneliness, a thing to care for when she can barely take care of herself, but that obviousness is because this kind of bad decision-making based on emotion, that need to simply hold something sweet, happens all the time. If not a baby, a puppy. And you can almost hear another junkie telling the story, as if this scene was shot in flashback – the saga of the short life of the puppy, an anecdote rambled on about before nodding off on a park bench. I thought of the cat in Trainspotting, a much more elaborate story, but another bad decision: the cat bought for the girlfriend who rejects it and then the poor guy stays in his apartment with HIV, alone, not taking care of that kitty. He winds up dying from the cat – toxoplasmosis. The difference, and perhaps, unexpected tragedy being that the young man doesn’t even die from an overdose – his condition worsens, brought down by the sweet little kitty.

But the unexpected ending of The Panic in Needle Park is that both Bobby and Helen live. You’re practically waiting for one of them to slip permanently into the abyss and, for a brief moment before expiring, feeling what one of the characters calls the greatest of all highs – death. But they don’t. And that feels strangely more depressing. Most likely the two are just going to continue on with the same routine. There’s no kind of closure. Helen has ratted out Bobby who winds up in the slammer but in the end, she’s there for him, whether for love or for desperation or for just not wanting to be alone. Or for all of those reasons. So, there’s Helen waiting for him, the only person to greet him. Almost like romantic, sweet Bobby was waiting for poor Helen when she was released from the hospital, after he visited her playfully looking for that scarf, only now they know each other, there’s no romance in this reunion. Maybe that will dissolve once they shoot up again and they’ll feel good for a while. But for now, Bobby simply says, “Well?” Helen walks along with him. Well, she’s not alone.

From my piece published at The New Beverly