Jonathan Demme has passed away. To honor his life and his musical, deeply humanistic films, in love with the odd and the beautiful, and the oddly beautiful, the art of everyday people who aren't so everyday, and the depth and complications of love — I'm posting my New Beverly piece on one of the great films of the 1980's — Something Wild. Rest in peace, Jonathan Demme.

“I’m glad to see you finally made it to the suburbs, bitch!”

Love can be traumatizing. It’s also exciting, unsure, bizarre, freeing and imprisoning (at times, somehow, simultaneously), and when it starts – that delicate, vulnerable starting point – there are messy shifts in mood that mirror a kind of mental illness. It might even be a mental illness, an abnormal interruption of serotonin levels causing mania, anxiety, depression and obsessive compulsive behavior. Of course that sounds more troublingly clinical than romantic, and people really don’t like viewing themselves as mentally unstable lunatics while in the throes of lovesickness (this is the socially acceptable sickness, one tells oneself), but if you read British clinical psychologist Frank Tallis (who wrote an entire book about it), you might be convinced of its psychopathology: “Love seems to have the power to destabilize people emotionally. Particularly in vulnerable individuals, it can be very difficult to cope… Some people are referred to me because of an admission to depression or anxiety disorder, but in fact, once we’d explored issues around their problems, it was clear they were just in love.”

With that kind of dysfunctional amore in mind (isn’t it always at least a bit dysfunctional?), Jonathan Demme’s moody, transgressive, genre-bending, weirdly romantic (and unromantic) Something Wild isn’t such a strange hybrid. For a love story, it mirrors what often happens when people do fall for another – it’s destabilizing and terrifying. A movie that upsets some viewers with its stark shift in tone – from winsome, sexy, romantic comedy to violent, obsessive thriller – it stares directly in the faces of its male protagonists – one, a dorky stuffed shirt type, the other, a charming, murderous criminal, and wonders if they are at all so very different. And in an especially powerful scene utilizing the Demme close-up, it wonders if anyone is at all so very different.

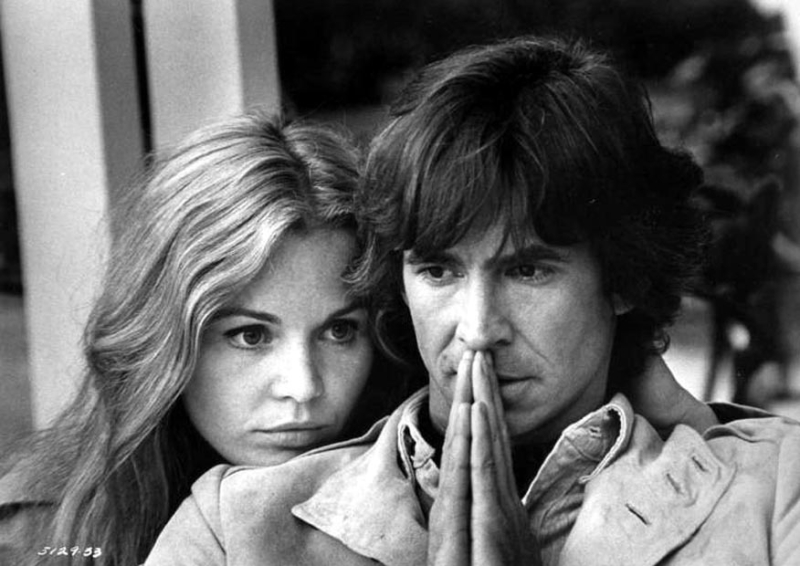

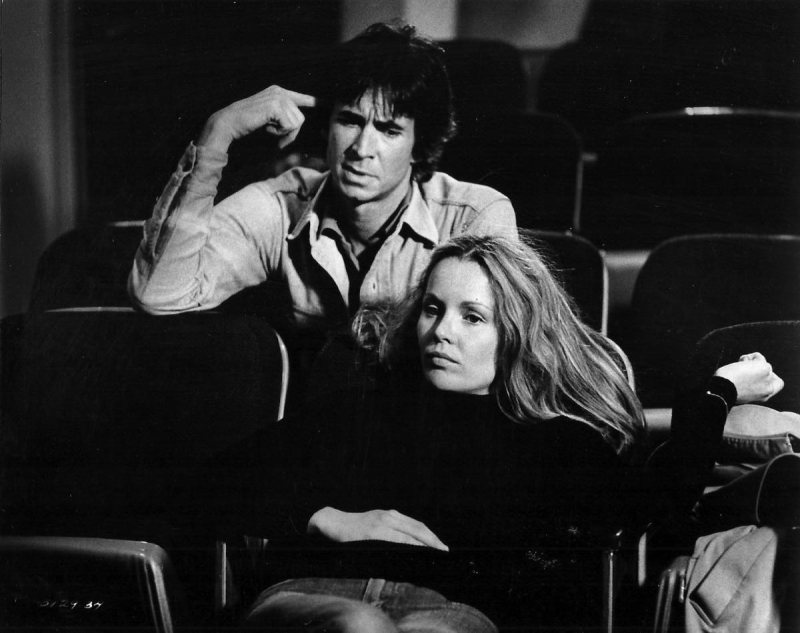

This question, through shifts of persona and the crazy act of falling in and reclaiming love, makes the character’s desire to embark on a quest, whether it be a journey through the past (to quote Neil Young), a new identity or the liberating adventure of a road trip, all the more poignant and unsettling. And relatable. It begins when the buttoned-up, newly appointed vice president of a Wall Street firm, Charles Driggs (Jeff Daniels) commits a sneaky criminal act for his own personal thrill – he pockets a check in a Manhattan diner and walks out without paying. Spying him is the pretty Pandora’s Box of a woman, appropriately named Lulu (Melanie Griffith) sporting a Louise-Brooks-bobbed wig and African jewelry – this is not the type typically drawn to Charles. The dark-haired stranger follows him outside and confronts his “closet” rebelliousness of which he protests – he made a mistake! He’s already lying. Once he learns that she doesn’t work there and that she doesn’t actually care that he lifted his lunch (she’s, in fact, turned on by it), she offers to drive him to work. Work doesn’t happen. Instead she takes him to a seedy motel room in Jersey where they have handcuffed sex to the tune of Fabulous Five’s “Ooh! Waah!” Natural to all uptight men confronted with the free-spirited, screwy dame going after what she wants (in movies), he’s reticent at first, but succumbs, which isn’t that tough. After all, sex is involved and Demme does not shy away from showing the eroticism of this encounter, allowing Lulu to enjoy herself and take control. You also sense something more problematic going on with this woman. Maybe she has a drinking problem? What is she evading?

She has other aims too – thinking Charlie (he’s now anointed Charlie) is a square (but rebellious enough to ditch a check), and a decent-looking, upstanding fellow, she convinces him to join her on a road trip to her Pennsylvanian hometown. It’s her ten-year high school reunion and she needs a fake husband to tag along. She also needs to show him off to her sweet mother, Peaches, who, in a charmingly affectionate scene, tells Charlie she knows Lulu (now going by her real name, Audrey) is pretending. She says nothing to Audrey about it; Peaches accepts her daughter’s impersonation of a “normal life” likely touched by the need to please her mama. This is the first tonal shift in the picture and another alteration (or doubling) of what men desire – going from the fantasy of the erotic, madcap siren to the toned-down, sweet, high school vision – the lovely woman, the kind Charlie could take home to his mother. From the so-called whore to the proverbial Madonna, she cleans up well. But why on earth this woman cares about her high school reunion shifts her to a place decidedly more squaresville than the viewer originally imagined. She saunters into the ballooned, name-tag wearing event as nearly an all-American girl, albeit the wild one – the blonde hair, the pretty white dress, the white shoes. But even before the dark force of romance past shows up, there’s an edge to this presentation, enough where, you can almost hear the song Demme used so powerfully in a film he hadn’t made yet, The Silence of the Lambs – Tom Petty’s wistful, mysteriously spectral “American Girl.” Here it’s The Feelies (fantastic) singing the mournful, menacing “Loveless Love,” and the guy remembering that girl thinking, “there was a little more to life somewhere else,” turns out to be Ray Liotta.

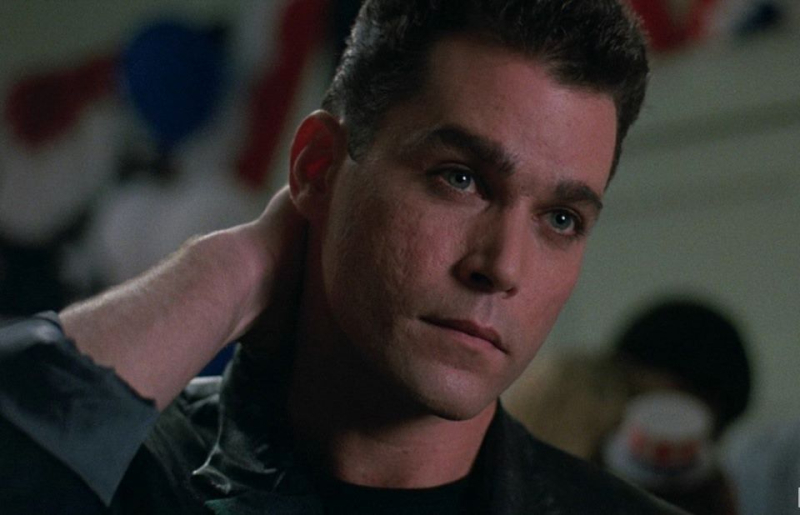

This is when the movie is akin to Bringing Up Baby as interrupted by Born to Kill, with an obsessed, jealous Lawrence Tierney pistol-whipping Cary Grant and kidnapping Katharine Hepburn. Can you imagine that? Demme did. The kooky, sexy girl isn’t so much charmingly incorrigible any more, and she instead brings with her menacing, abusive baggage. There’s now a reason why she’s drinking so much. And being the estranged wife of a criminal, she might even be complicit with this psycho (what did they do together in the good old days?). And yet, Liotta’s Ray, all blue-eyed and charming with his rough trade handsomeness, freshly sprung from prison, isn’t immediately a threat to Charlie. Charlie likes him, in fact. Charlie’s so stupidly loved-up at this moment, he’s both naïve and not paying attention; he’s not even paying attention to Audrey’s nervousness, so self-absorbed he is while indulging this new love-struck feeling. He’s also caught up in the masculine energy of Ray.

Through Demme’s direction (and his brilliant cinematographer, Tak Fujimoto), Ray’s entrance is something to behold – the camera moving in on Liotta’s smiling, ominous face, we know this guy is chaos. We’re also positively struck by Liotta’s charisma – it hits the viewer so much that they feel a dark thrill, even a kind of love at first sight. Liotta is scarily sexy in this movie and Demme knows it, aptly understanding that being drawn in by Ray is going to become something more complicated than merely rooting against a stock villain. We even feel for Ray at times, in spite of how inexcusable his actions are. After all, he’s in love too. Even worse, he’s still in love, and she doesn’t love him anymore. Thinking back to love as mental illness, that might make you crazy. Add prison time to unrequited emotions, and you’ll be even more incurably “romantic.”

Intelligently allowing Ray to partially take over the picture, Demme (and screenwriter E. Max Frye) raise the stakes, making us question how we feel about this smiling jailbird. He’s so fit and so focused and so fucking damaged. And yet, he’s appealing. When Demme has Ray turn so shockingly violent (it’s not cute) he becomes some kind of nightmare delirium of jealousy and fear – namely Charlie’s. As if, when a woman talks about her most recent ex, the bad boy ex, and her new boyfriend wonders, worried, what their relationship was like. How will he measure up? In this movie, that guy appears, not only taking her away, but also taking her away with charm, brutality and mockery. Ray tests Charlie’s masculinity so much, but with such a powerful combination of desperation and violent angst, that the viewer, and perhaps Ray, questions what being typically masculine means in the first place (a question Demme studies in other films, and directly after this one with Matthew Modine’s heroic, but quirky straight arrow F.B.I. agent in Married to the Mob).

And yet, Charlie takes to him. You understand why. He feels stimulated being around the animal magnetism of Ray. At first. And then, again, the story shifts, the mood gets darker, and boy meets girl becomes boy meets boy, transforming into two boys pursuing one girl, albeit with different means. Or are they so different? They’re both, in a fashion, and in their own kind of feverish love, chasing/casing Lulu. Charlie is, of course, saving her, and from obvious threat, but what is he releasing her from, really? And does she have much choice in the matter? Does she even really love Charlie?

Perhaps it wouldn’t have gone so terribly awry had Audrey done something she shouldn’t have to do and simply told Ray she still loved him – as in, lied – but he seems like the one person she can’t lie to. Charlie’s fibbing about his wife and kids (revealed via Ray) and that lie pisses off Audrey enough that she resigns herself to Ray’s entrapment. The kinky S&M she brought to Charlie is no longer role-playing, it’s real, and the veneer of Charlie’s normalcy and of Lulu’s uninhibited allure is fully lifted (when rewatching the picture, we’re observed it slowly revealing itself from the beginning, however). How we present ourselves when falling in love, what we want that other person to see (and notsee) and often, what we choose to ignore, undergoes a transformation here, with Charlie and Lulu gazing at each other in the exposing bare light bulb glow of Ray. Gee, is this movie any fun? Yes, it is.

What’s so wonderful about the picture (among other things) is that while skating on the edge of a potentially joyless thriller, it never becomes one, even as it upsets you. It’s still fun and, importantly, it’s still moving. In Demme’s view of this particular corner of America, there’s life and joy bursting out of every frame. With the picture’s music (49 songs) providing such a singular, superb soundtrack to these lives, people serve not just as scenery but as distinct individuals, sometimes poignant, sometimes musical. Among many stand-out, small performances, there’s a group of rappers outside of a gas station market, an inquisitive girl checking in on Charlie as he sits in his car, and a lovely moment in which Charlie engages with a clerk named Nelson (Steve Scales) who helps him pick out attire from the tacky tourist gear. It’s delightful, how long Demme allows this scene to go on and how much he, Daniels and Scales underplay what could have been a rote “wacky” incident. Charlie is changing in the store (appropriately in a “Virginia Is For Lovers” tee shirt) and Nelson is not at all perturbed by this, instead he’s encouraging, even casually life affirming. When Charlie asks Nelson if he should buy new glasses (he’s wearing Lulu’s colorful kiddie-looking specs) Nelson says, “Nah, keep ’em. You’re beautiful.” The world is not such a shitty place after all.

Within that strange, disarming world, cameos like John Sayles as a motorcycle cop, Demme favorite Charles Napier as an angry cook and John Waters as a used car salesmen fit right into the environment without any kind of showy strain. I especially love a small moment when, after Charlie has rescued Audrey from Ray, Ray sits angrily by a diner window trying to figure out what to do. An extra passes by outside, saluting him with a little wave. Just a little wave. It’s a humorous and endearing punctuation mark. Soon after, in that same window, a young woman Ray’s already flirted with at a gift shop, cheerily taps on the glass, and seeing his way out, Ray exclaims “Oh, thank you lord!’” He kisses the window and then manically laughs to himself. You kind of love Ray at that moment – just for being so damn charming and resourceful. And amused. It’s infectious.

Which is why Ray’s final moments wind up so strangely touching. He’s not without his own vulnerabilities; we’re not hoping he dies. We’re not sure what we’re hoping for. As mentioned earlier, Demme employs his now famous close-up shot; the character’s eyes full of sadness and regret, staring at each other, and we look directly at them. In some ways the two men merge at this moment, provoking complex feelings of identification, fear and empathy. This is not a happy ending. Charlie will never be the same. But who was he in the first place? And who is Lulu? Not long before this moment, Lulu/Audrey asks Charlie: “What are you gonna do now that you’ve seen how the other half lives?” He says, “The other half?” She answers: “The other half of you.” Good question.