The Searchers: Debbie and Martin

From my piece written for the New Beverly.

What will happen to Debbie? What will happen to Martin? I always ponder this when watching the ending of John Ford’s masterpiece, The Searchers. Most certainly I’ve long soaked in, reflected on and studied the famous final shot of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards, standing outside that beautifully-framed doorway — the warmth and domesticity, darkened, on one side, the light from the frontier of Monument Valley on the other — he’ll roam lonely and damaged, never fitting in civilized society, never fitting in anywhere. The past is the past and he’ll reject it, and he will be rejected from the future (no one invites him inside). Ethan stands solitary in near purgatory, much like the dead Comanche he ruthlessly shoots in the eyes earlier in the picture, wandering “forever between the winds.” Even with his final forgiving act towards Debbie, there’s no redemption for him. There’s no saving him from himself — he will remain dark and demented and a question mark to Ford lovers: “Do I feel for Ethan?”

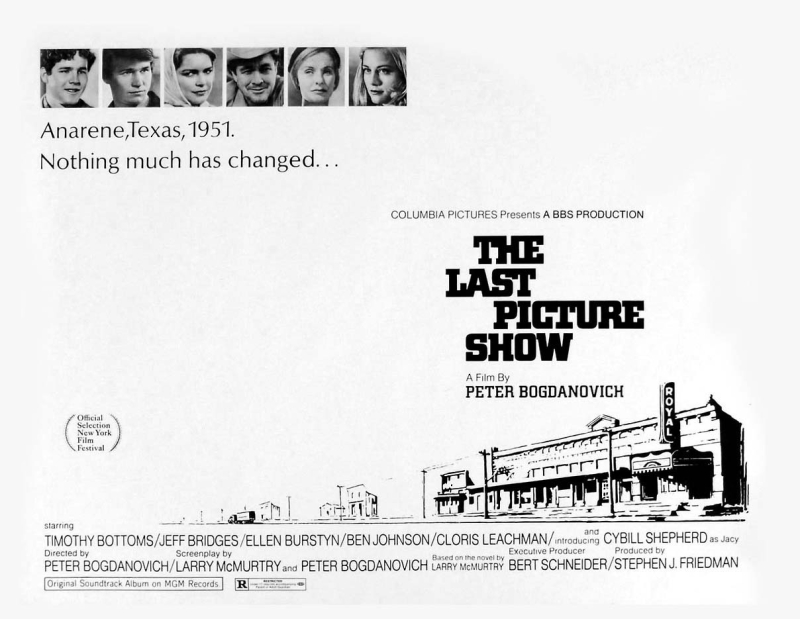

It’s one of the most famous shots in film history, inspiring filmmakers from Francis Ford Coppola’s fade to darkness door-shutting scene of The Godfather to Vince Gilligan’s finale of Breaking Bad. The movie is notably worshiped and studied – Ford biographers, notably Scott Eyman and Joseph McBride’s impressive tome dig into the movie and Ford, and directors Jean-Luc Godard, George Lucas, Paul Schrader, Peter Bogdanovich, Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese are among the famous, much-discussed, passionate devotees, so much that it’s been a point of annoyance for a few film critics who have reassessed it as overrated, offensive or, worse, boring. Xan Brooks at The Guardian questioned why it’s been so canonized with, “They [those who love the film] misinterpreted a tentative shuffle-step as a giant leap forward and hailed the film as a revisionist masterpiece as opposed to a stumbling reconnaissance.”

One of the most interesting and best essays comes from Jonathan Lethem, who wrote “Defending The Searchers,” which covers his decades-long love of the movie; how he wrestles with the picture at different stages of his life, what it means to him and how he views it. He wrote, “The film on the screen is lush, portentous. You’re worried for it.” Anyone who has seen and admired The Searchers multiple times, drawn into Ford’s poetry and stunning compositions, finds something to think about and drink in, often beyond what they thought of from their previous viewing. Scorsese claims to watch The Searchers at least once or twice a year and in doing so, discovers something more to reflect upon. In a 2013 column for The Hollywood Reporter Scorsese wrote:

“Like all great works of art, it’s uncomfortable. The core of the movie is deeply painful. Every time I watch it – and I’ve seen it many, many times since its first run in 1956 – it haunts and troubles me. The character of Ethan Edwards is one of the most unsettling in American cinema. In a sense, he’s of a piece with Wayne’s persona and his body of work with Ford and other directors like Howard Hawks and Henry Hathaway. It’s the greatest performance of a great American actor. (Not everyone shares this opinion. For me, Wayne has only become more impressive over time.)”

He’s right. The movie is uncomfortable, but not solely because of Ethan, it’s uncomfortable for Debbie and for Martin as well. Because walking through that famous door is teenager, now-a-woman Debbie (Natalie Wood), tentative, traumatized, the widow and “polluted” white woman of the slain Comanche, Scar (Henry Brandon), and her adopted brother, Martin Pawley (Jeffrey Hunter), the part Cherokee (one eighth) who spent all those years protecting Debbie from murderous Uncle Ethan while enduring his uncle’s humiliations and racist ridicule (“Blanket head”) and Vera Miles’s hyperactive horniness (which isn’t so terrible, though she’s not exactly a likable character).

Indian-hating Ethan does grow fond of Martin (if you can call it that) along their five-year Homeric quest to find Martin’s sister, Debbie (kidnapped by the Comanche as a young girl after her family is slaughtered and raped), but Martin’s put through so much along the way, made the butt of jokes, in danger, I find myself admiring his resolve more and more every time I watch it. He pushes on in spite of his indignities. He’s not even allowed to drink in a bar. Martin works as the moral center of the picture but defies cliché. Like the intriguingly dark and amoral anti-hero Ethan, a guy who will shoot a man in the back, Martin, who would probably be more typically macho in another picture, is frequently aggravated to exasperation, lovable and comic, almost light, but, no… wait minute, he’s not light. Martin’s been through some heartbreaking hell: himself an orphan, rescued by Ethan years before after an Indian massacre, orphaned again after his adoptive family is killed. “It just happened to be me,” Ethan harshly hollers to the young man he refuses to consider any kind of kin. “You don’t need to make any more of it.”

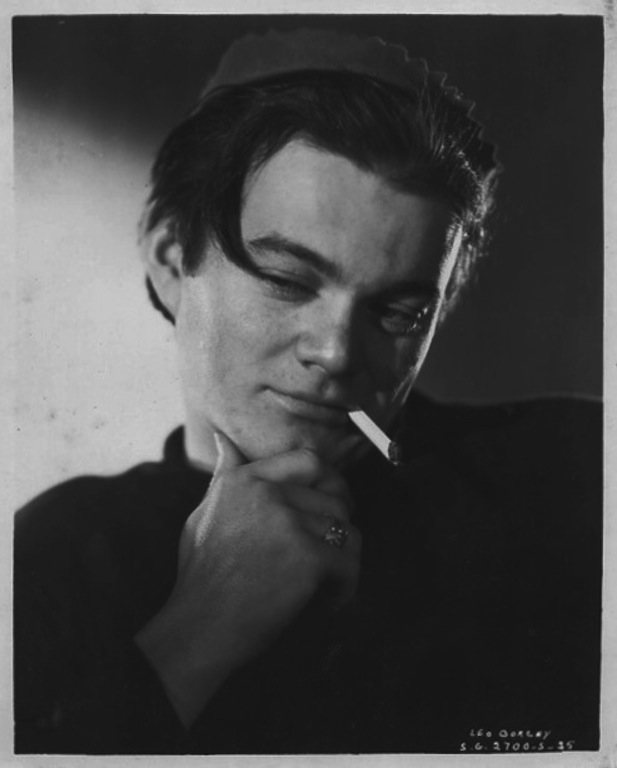

Resourceful and tougher than he seems, Martin’s passionate, even tortured, a defender of Debbie but also following along, sometimes in awe, to find anything forgiving in Ethan. Just the casting of Jeffrey Hunter (who would later play the most beautiful Jesus Christ in the history of Jesus Christs in Nicolas Ray’s King of Kings) seems a way to complicate Wayne – to irk him beyond his character’s Cherokee blood. Martin’s youth, goodness, beauty, and real liberalism towards his sister (he does not think her virtue destroyed by Indians) is decent and lovely. It’s also somewhat radical and reflects how complex and murky John Ford was on these issues as well.

But Ethan is such a force, he exudes so much presence and fearsome qualities, that he overtakes nearly everything, distracting or perhaps even diluting Martin’s heroism. This is to the picture’s credit since Martin builds and grows on you and grows on Ethan as well, so much that he becomes some kind of sneak attack of intractable sensitivity. Viewing Martin, at first, as a well-meaning greenhorn, hotheaded but insecure and sweet, a sort of apprentice to Ethan, it’s extra moving when he bravely shields his sister from Ethan’s gun. That scene hits you hard; it’s mightily emotional and potent to the point that it takes you aback (don’t forget – this is her brother – and Martin is not some novice). At that moment, Martin is braver than anyone in the movie. If anything happened to him, you’d be brokenhearted. I would be.

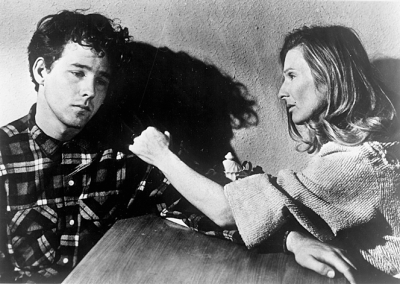

The scenes between Debbie and Martin are so touching and, to me, as powerful as Ethan famously holding Debbie aloft at the end of the picture (“Let’s go home Debbie”) – not killing her. Wood and Hunter connect on the screen so lovingly and so strongly, that I’ll transfer what Franzen said about the movie and place it on brother and sister: “you’re worried” for them. What will happen to them? Again, this takes me back to the end, when I think of the two beaten-up beauties walking through that door. The family welcomes them with open arms, but will society? And will the family remain so open? Debbie will now have to learn to live outside of the Native American world she’s become accustomed to and brother Martin will doubtlessly marry Laurie (Vera Miles), who expresses her own racism when she complains of their search for Laurie: “Fetch what home? The leavings a Comanche buck sold time and again to the highest bidder, with savage brats of her own? Do you know what Ethan will do if he has a chance? He’ll put a bullet in her brain… I tell you, Martha would want him to!” Martin answers, “Only if I’m dead.” Laurie throws in Martin’s dead mother on top of her racist repudiation? Jesus. You wonder how Laurie and family reallyare going to treat Debbie once she’s “home.”

Laurie also seems more sexually obsessed with Martin than in love — she can’t keep her hands off of him and delights seeing him naked while he’s demanding privacy during a bath. She’s sexually aggressive to the point of obnoxiousness. There’s nothing wrong with that and who can blame her? She’s lonely out there and it is Jeffrey Hunter after all (who shows up looking like that?) but it’s intriguing just how much Martin is objectified in the movie, much more than the women. Often shirtless, soaking in the bath shielding his body like a bashful woman, rolling around in blankets, or just ridiculously gorgeous, those blue eyes burning a hole through Ford’s lyrical, magnificent frames, Hunter’s beauty occasionally makes you gasp. It’s also a source of Ford’s humor, particularly his romantic mishaps (and the entire wedding sequence that goes haywire), but also underscores his difference from others. When first introduced, Martin, all sprightly and smiling, is riding Indian style – bareback.

In some ways, he’s more akin to Scar (also handsome, also with alarming blue eyes) whom his sister is sleeping with (never said, but clearly the idea of sex with a savage further fuels Ethan’s murderous fury). According to Hunter in a 1956 Picturegoer Magazine profile, the young actor met Ford in his office with slicked-back dark hair, wearing a “very open-necked sports shirt to display a healthy tan.” John Ford sat at his desk smoking a large cigar, stared at Hunter “for what seemed an endless time, then grunted: ‘Take your shirt off!’ Hunter replied as if Ethan was barking at him and recalled, “I did just that.”

Reading Glenn Frankel’s impressive, exhaustive book, “The Searchers: The Making of an American Legend,” gives insight into the true story and the layered mythologies around the kidnapping that inspired the novel and the movie. And it makes you contemplate Debbie’s fate after going “home.” Cynthia Ann Parker was the real-life Laurie, a Texan girl who in 1836 was abducted by Comanches after they attacked and killed her family. She spent 24 years with the Comanches, married a war chief, presumably loved him and birthed three children. In 1860 the U.S. Cavalry and Texas Rangers came to her village and she once again witnessed the slaughter of her family. When they realized she was white, she and her baby were returned to what was left of her family. But she wasn’t happy. She was now a Comanche, did not want to be a Christian or to live in the white world outside of the Indians. She remained depressed and lonely for the rest of her days – an absolutely shattered figure.

From that tragic story, a mythology was woven and expanded as her Uncle (who obsessively searched but never found her in real life) was transformed into the protagonist of Alan Le May’s 1954 novel “The Searchers” from which Ford’s 1956 picture was adapted. From real life to mythology to novel to screen, the tale twists and turns and bends but one thing remains: the captivity narrative being a popular western tale, bringing up all kinds of issues and ideas about conquest and even eroticism. As Frankel stated in an interview:

“It raises all of these difficult issues. At the same time, besides all of this sort of personal and psychological tension involved, it becomes a sort of justification for the conquest of the West … So there are these psychological, psychosexual tensions involved, there are these imperial notions, and Americans continue to tell these stories. Around the time Cynthia Ann was kidnapped in 1836, if you look at the bestseller list, three of the four top bestsellers in America are James Fennimore Cooper novels, all of which have captivity themes. And then the fourth one was a non-fiction book about Mary Jamison, a woman who was captured by Seneca Indians in upstate New York in the 18th century.”

He also said, “There’s something about being in this land and having the ‘other’ savages, these people, these natural, scary, people, come and take you, take your family, take your wife, take your children, and haul them off into the wilderness. It’s scary, and it’s a little bit sexy.”

That sexiness horrifies Ethan. Or he’s drawn to it. After all, we’ve no idea what he’s been doing during his long wanderings, learning the Comanche language, understanding their customs. It would not be a surprise if he’d slept with many Native Americans or harbored an attraction (though the poor Squaw who accidentally becomes Martin’s bride is treated with cruel humor, only to be met with selfless tragedy – Martin and Ethan appear visibly guilty). Ethan is the dark heart, perhaps in his case, additionally the broken-hearted (and not just romantically – for his past forbidden love of Martha), blood-soaked history of violence and domination of the West, but a man who must contend with the likes of Debbie and Martin and… soften. He cannot kill Debbie, even if he believes her sullied by savages, and sticks with Martin, whom he spends many a night with, five damn years in fact (as Roger Ebert asked in his review, “What did they talk about?”). Ethan will never really approve of brother and sister, he’ll never be friends with Martin (even after bequeathing everything to him, which Martin rejects on behalf of Debbie), but Ethan has a little in common with those he’s saved, more than he knows. Or perhaps he does know this. These three are not at all “normal” and they are all going to endure some strangeness in their futures. Martin has been through enough to prove his resiliency but… Debbie?

So, that doorway shot, Ethan standing outside representing the past, Debbie and Martin, walking in, the arresting exotics of the future, what will become of them? Thinking of Frankel’s thoughts and deep study of Cynthia Ann Parker, Martin and especially Debbie, whom the picture suggests will be loved by their families (even if Laurie previously proclaimed Debbie better off dead), will likely become objects of sexual fascination and hatred of miscegenation from the outside world. With Debbie “home” protective, liberal Martin has a lot more defense ahead of him. He’ll surely repeat the same he said of Ethan concerning other angry men and in different circumstances: “He’s a man that can go crazy wild, and I intend to be there to stop him in case he does.”