John Cassavetes’ Too Late Blues

Showing tonight at the New Beverly. John Casavetes' sublime, underrated "Too Late Blues."

“I am trying to show the inability of people to recognize that society is ridiculous. Hardly anyone obeys the mores, but they respect them. If they are exposed breaking the mores their lives can collapse. Our hero is not a coward, but in covering up this failure he destroys everything else that is important to him. A silly search for mores reduces the great, wonderful hero of the story into a cheap individual with no morals and ethics and no place to go.” – John Cassavetes on "Too Late Blues"

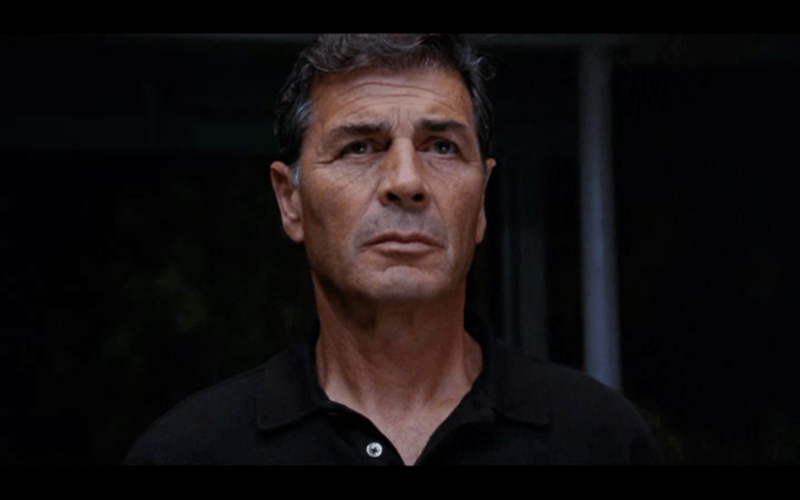

Everyone in Too Late Blues is miserable. And I mean miserable. That is in no way a condemnation of the picture, not at all, as this is a beautifully realized collection of melancholic musicians (also an agent, B-girls, a couple of bartenders and a touchy tough guy) who are depicted as humanely, compellingly miserable in a way that only John Cassavetes (who co-wrote, with Richard Carr, and produced and directed the picture) grooves on with his particular kind of dignity for the defeated. Some don’t know how miserable they are, they’re even laughing and exuberant at times, but we can feel it throughout the picture – it just hangs over these characters with their respected musical purity and perilous futures in a world that manages to grind down your purity and grind down your debasement (and yes, the world can grind down your sullying even more than you thought). Though none of these individuals are really trying to maintain a bright outlook since they know how life goes, they’ve been around. They’re also not ready to chuck away their dreams even when they go “commercial” (for a time). That should be a positive. It is. In an easier world. And so they walk from room to room, bar to bar, gig to gig, haunted. It’s no wonder the lead character’s name is Ghost (Bobby Darin) – his ego might ruin him to that fate – a potential phantom, a guy people talk about from the past, leaving stale smoke and circles on bars behind him while maybe, just maybe his real music will be playing somewhere, a memory. Or maybe he’ll make it his way. Cassavetes did (but by 1961, while he was directing this picture, he hadn’t yet), and one can’t help but see the anxious, questioning parallels between Ghost and Cassavetes.

Darin’s Ghost Wakefield is a mushy-faced jazz cat and some might argue he’s miscast. He’s not. His drive to keep his artistic integrity, no matter if his band complains about playing in parks to birds and trees, living off nothing, is portrayed with the drive of a guy with lots of talent, lots of charm, but a hell of a lot more insecurity than he’s letting on. Darin in real life was a mushy-faced singer with loads of talent and though he was popular, he always seemed a bit off-center, not quite as cool as he would have liked, but not as square either. In Too Late Blues Darin entirely gets the anger and ego of a guy with talent to burn playing dumps, fighting during recording sessions and dealing with scummy agents while trying to do what he loves. He’s seen this world before. You can tell. And he’s both poignant and completely unlikable all at once.

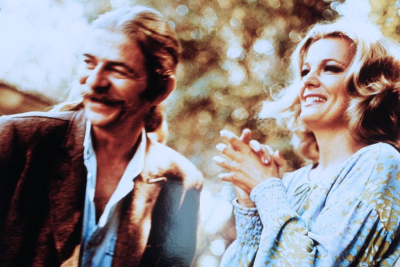

You can also tell that Stella Stevens (who plays Jess) the beleaguered B-girl and singer, has seen some sleazy situations in her time. Fresh off her Playboy 1960 Centerfold and just a few films roles she floats into the picture a petrified beautiful bird, nervously scatting with a seasoned jazz pro and ends it a suicidal wet-haired feral cat, once again singing in her wordless, almost disturbing near incantations. She’s heartbreaking – a broken young woman who has been so used, she can slip from quiet, contemplative junkie (without ever shooting up – her character just oozes opiate addiction and trauma) to drunk and boisterous to runny-eye-makeup, furious good time girl. She’s acting a part when she’s out hooking sliding right into the role men want her to be, but when she’s faced with actually loving someone (in this case, Ghost) she’s an emotional wreck. She’s also so vulnerable that one contemptuous moment from Ghost and she’s gone. She sleeps with his musician friend who is, as she says, bigger than him. She repeats this with emphasis so you get that she doesn’t just mean taller.

And yet, the film never judges her. Cassavetes is so understanding of this kind of woman that the picture feels downright radical in that regard. She’s not just a whore – she’s not even sure what she is – and that’s sad, not ugly. And Ghost (who will become kept himself by a rich woman playing music just for the scratch) well, what right does he have to judge? Ghost may represent the movie’s mixed idealism and egoism of holding onto your vision, but Stevens is its vulnerable center. She’s spinning from one place to another, even a baseball field, with all of these men swirling around her either telling her she’s worth something or distracting her from the purity of not just music (for she can sing) but of her own self. She is so down and depressed that her later, very physical meltdown in a bathroom is so shattering it almost takes you by surprise. We knew she was despondent and yet, she’s so brilliant in this moment, we are genuinely taken aback by just how despondent she really is. As Cassavetes reflected: “I see women in bars, crazy girls who don’t want to be themselves and who don’t want to admit what they are. They’re difficult people. They’re hard to talk to. But to me they’re like a mother; awkward, pretty young girls.” He’d known these women. And, again, Stevens must have, too. She’d likely known these men.

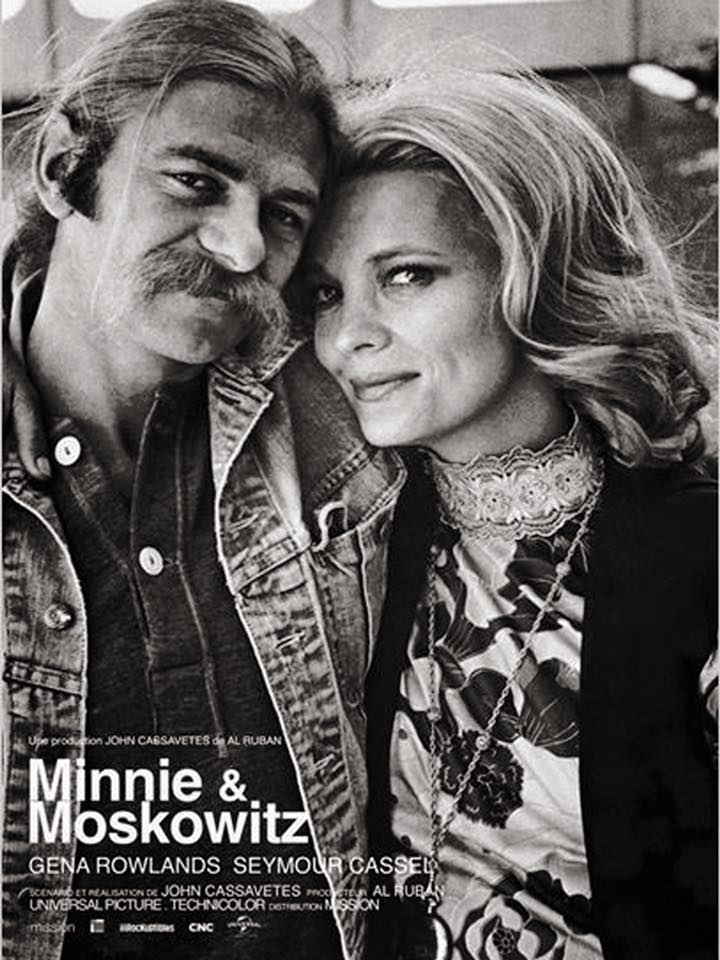

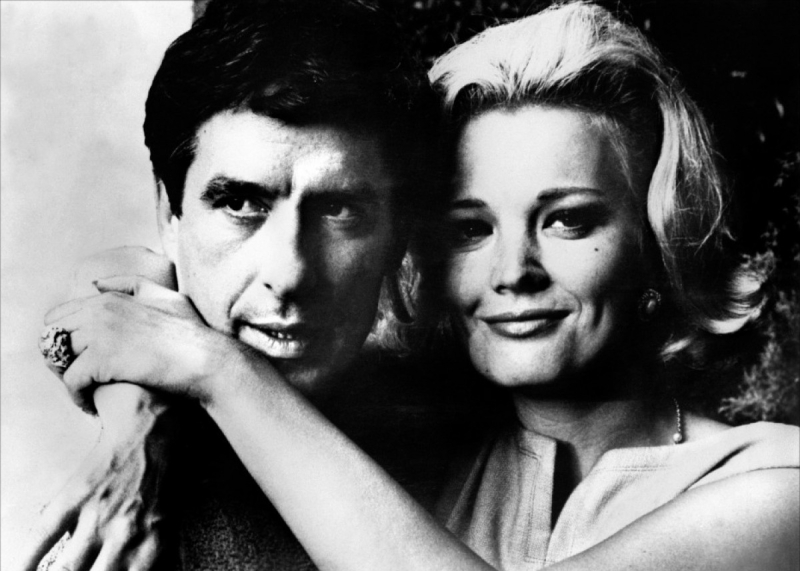

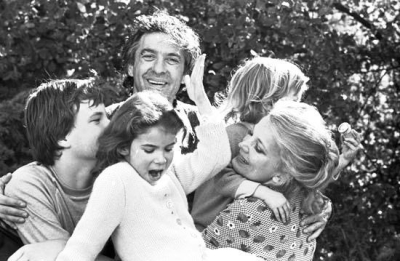

And Cassavetes knew about the struggle of working for dough. This was Cassavetes’ second picture after directing his groundbreaking, independent Shadows and starring in his “commercial” TV show, Johnny Staccato, and his first time directing under a studio (Paramount). He was allowed neither his casting choices with the leads (he wanted Montgomery Clift and his wife, Gena Rowlands) nor his preferred location (he wanted New York City, the film was shot and set in Los Angeles), but, according to Ray Carney’s ‘Cassavetes on Cassavetes,’ he felt some optimism bringing most of his trusted friends and crew along: Shadows cast members Seymour Cassel, Cliff Carnell, Rupert Crosse and Marilyn Clark; Johnny Staccato actors Val Avery and Everett Chambers; American Academy of Dramatic Arts alums like Bill Stafford, James Joyce and Vince Edwards. Both his co-scripter and his cameraman (Lionel Lindon, a veteran who also shot for John Frankenheimer, including The Young Savages, All Fall Down and The Manchurian Candidate) worked on Johnny Staccato. He was given freedom in spite of some stipulations, and he worked beautifully with his cast and musicians (Shelly Manne, Red Mitchell, Jimmy Rowles, Benny Carter, Uan Rasey, Milt Bernhart a score by David Raskin, and Slim Gaillard shows up in the film as well).

The picture is also gorgeously shot, the black and white cinematography giving us a life where men and women live, play, fight and drink by night, only to look strangely awkward in the daylight (Ghost remarks how beautiful Jess looks in the sunlight partly because she’s never in the sunlight). Though it has less the ragged experimentalism of Shadows, the composition and interiors and the lack of an actual street life (it’s just a lot of darkness out there, or a depressing pool lighting up the outside of Jess’ pad) powerfully conveys the claustrophobia of club life. One second it’s fun and dancing, the next it’s Vince Edwards punching and screaming about needles in pockets, hollering about dope fiends. Everything feels entombed and perilous all at once. Never mind how anyone breaks through this life, how does anyone breakthrough this room? The picture is something near a masterpiece.

But, never mind all that. Like Ghost compromising his 100 percent artistic vision, Cassavetes wasn’t happy with the end result. He didn’t get the edit he wanted (and that edit would have been interesting, likely greater than this one). The movie didn’t do well and some of those ready to attack him for going commercial jumped on him. He wound up making another picture for Paramount that proved even more upsetting (A Child Is Waiting) and would eventually make one of his finest films, Faces.

As Cassavetes said about working with the studio: “All I care about is making a movie I believe in. Everyone else in the room with me, they’re concerned with figures rather than people and emotions. They only care about money. There are no artists in the room with me, only bankers. I’m all alone.”

Making art just for money? Compromise? Thankfully, Cassavetes created his own kind of career so he wouldn’t have to. But, Too Late Blues’ Ghost? He might get the group back together and go places. Other than that, he’s miserable. Miserable in a magnificent movie.

KM: You're vocal about the pay disparity between men and women in Hollywood. And that women and men together, need to work with and discuss women in film…

KM: You're vocal about the pay disparity between men and women in Hollywood. And that women and men together, need to work with and discuss women in film…